|

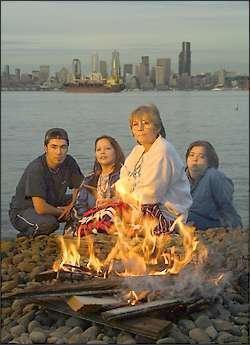

TOM REESE / THE SEATTLE TIMES

|

A LINK TO THE PAST

"We are still here; we still exist," says Cecile Hansen (center), the great-great-grand niece of Chief Seattle and current Duwamish tribal chairwoman. With Hansen on Alki Beach, about a mile from where the Denny Party touched shore, are (left to right) her foster son, Mike Bush, daughter Barbara Lynch and granddaughter Alichia Summers. |

One hundred and fifty years ago today, Seattle was neither a city nor a village. It was nobody's name. It was not even a word.

All of this would change soon enough. Less than six months later, on Nov. 13, 1851, five pioneer families now known as the Denny Party put ashore at Alki Beach, putting in motion events that led to a modern Northwest culture and virtually destroyed an indigenous one.

Initially, they named their landing place New York Alki, an ironic use of a Chinook word meaning "by and by."

Three months later, the founders moved to a better site on Elliott Bay and named it Seattle, an Anglicized approximation of the name of the kindly Native American chief who had welcomed them to his homelands.

By and by, the sarcastic reference to New York seemed prophetic, as Seattle's wealth, downtown skyline and traffic turned increasingly Manhattanlike.

But Seattle is at no risk of becoming New York. It is a city with its own unique setting, history and identity. For all its skyscrapers, Boeing airliners and espresso, Seattle's real roots run as deep as Puget Sound, as wide as Mount Rainier and a gray winter's overcast.

|

|

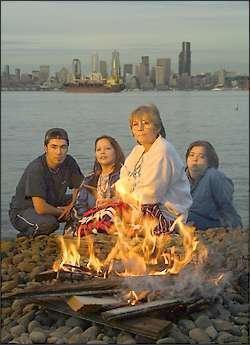

Chief Seattle, leader of the Duwamish and related native groups, welcomed the Denny Party to his territory. |

| MSCUA, UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON LIBRARIES, NA1515 |

To understand this city, we begin with who and what was here before it was a city - the dramatic environment that persists despite a century and a half of profound change.

Nobody feels those links more passionately than Cecile Hansen and James Rasmussen, descendants of the Duwamish families who lived here for centuries before the Denny Party arrived. When they stroll the sidewalks of Pioneer Square, they see a clump of grass pushing through cracked concrete and are reminded of their ancestors. They walk the beach at Alki and see a place utterly transformed by two lifetimes of progress.

"Progress is progress, and I'm not against it," says Rasmussen, a jazz musician who also serves as the Duwamish cultural-resources manager. "But we need to be more sensitive to what was here before, and I think we're moving slowly in that direction."

Before the Denny Party

The place that became Seattle was wild but not a wilderness. To the settlers, it was a dark, daunting, impenetrable forest of giant trees, inhabited by "hostile Indians." But to the Duwamish people - a tribe that was more a collection of villages linked by language and family ties - that forest was home.

"The settler saw trees, endless trees," says David Buerge, a Seattle teacher and historian who is writing a biography of Chief Seattle. "The Natives saw the spaces between the trees."

The Seattle of 1851 would not be recognizable today. For about 10,000 years, Lake Washington drained to the south, via the Black River and the Duwamish. The hourglass-shape isthmus between Elliott Bay and the lake consisted of steep ridges running north to south, defining damp, forested valleys left by the Vashon ice sheet as it receded about 13,000 years ago.

The landscape of downtown Seattle was steeper than today. Denny Hill, long since flattened, overlooked Elliott Bay, which incorporated broad tideflats in the area now occupied by cement plants and Safeco Field. The mouth of the Duwamish was a rich estuary, similar to the Nisqually, laced with grassy islands and eelgrass beds, ideal habitat for shorebirds, juvenile salmon and spawning herring.

The place we now know as Pioneer Square was a small island, linked to the mainland at low tide by a sandbar. Propped on the island and mainland were several longhouses, a village that the Duwamish called, in rough translation, "Little Crossing Over Place."

Towering over the bluffs and beaches were the coastal forests. Arthur Kruckenberg, the University of Washington botanist and author of the popular "Natural History of Puget Sound Country," envisions a dense coastal forest dominated by Douglas-fir, western-hemlock and red-cedar trees, some of them 250 feet tall and 6 feet wide. The forest was dense with fallen logs that sprouted young trees alongside sword and bracken ferns, salal and devil's club.

Notably absent were plants such as English ivy, laurel and Scot's broom, along with hundreds more flora and fauna that would be introduced later.

For a taste of Puget Sound before whites arrived, Kruckenberg suggests visiting the old-growth forest at Dosewallips State Park on Hood Canal. Closer to home, a lesser glimpse of coastal forest ecology remains in some Seattle parks - Carkeek, Seward and Schmitz.

Scattered along those beaches, lakes and rivers were the people now identified as the Lushootseed Coast Salish. The Lushootseed language, whose clicks and throaty sounds are strange to English speakers, is actually a group of more than 20 dialects spoken throughout the Puget Sound area, explains UW scholar Coll-Peter Thrush.

Life on the shores of Puget Sound was probably less arduous, and certainly less transient, than that of most Native Americans. Food, fuel and water were usually abundant and accessible. The forests were home to deer and elk. Cedar trees provided the raw material for longhouses, canoes, clothing and more. Forest openings produced camas roots, seasonal berries and medicinal plants. Fishing weirs, ingenious traps that traversed the Duwamish and other rivers, intercepted salmon. The tideflats were home to clams and mussels.

|

Sunday, May 27, 2001 - 12:00 a.m. Pacific

Sunday, May 27, 2001 - 12:00 a.m. Pacific