| 'It dawned upon me that I had made a desperate venture. My motto in life was to never go backward, and in fact if I had wished to retrace my steps it was about as nearly impossible to do so if I had taken the bridge up behind me.'

— Arthur A. Denny |

|

|

Arthur Denny, pioneering West to build a new life and what would become the city of Seattle, had his mind set on Oregon's Willamette Valley. But a man on the Oregon Trail told him of a place called Puget Sound. Denny paused briefly in Portland, then left for Puget Sound, where he and nine other adults with 12 children landed 150 years ago Tuesday.

Portland was on its way to being what historian Donald Meinig has called "the undisputed capital" of the Northwest.

"There was plenty of publicity about Oregon," said Meinig, an Eastern Washington native and author of a four-volume geographic history of the United States. "Nobody was interested in the Puget Sound area. There was no settlement there of any significance at all. There's nothing to attract people. It's a wet, soggy land."

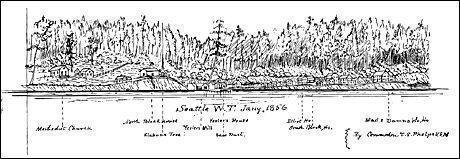

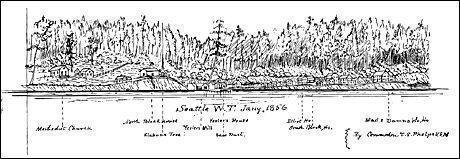

Seattle 1856: Seattle's waterfront was sketched by an officer on the gunship Decatur.

|

|

Yet today, it is Seattle that claims the title of undisputed capital of the Northwest. It is an axis of global commerce, the city that looks across the Pacific and into the world while Portland looks more inland up the Columbia River. The story of how that came to pass is in many ways Seattle's story.

Both cities started out with certain geographic advantages. Portland had farmland and water for navigation. Seattle had abundant trees and a deep harbor.

But then Seattle transformed itself. It marketed itself as the jumping-off point for the Gold Rush, carved down its hills and built a university. Later, it built airplanes, a futuristic World's Fair and a port handling more than $30 billion in goods a year.

Portland was the stable, agriculture-based family town. Seattle was the upstart, striving city driven by people of dynamic vision.

"These are aggressive Yankee entrepreneurs," said Lorraine McConaghy, historian for Seattle's Museum of History & Industry. "It didn't seem to them as if there was enough space for the city to grow in a way that they wanted it to so they began obliterating and changing with incredible confidence that there would be no unintended consequences that they couldn't deal with."

Steady rain greeted party

Seattle had an inauspicious beginning. On Nov. 13, 1851, as the Denny party stepped off the schooner Exact at Alki Point, it was raining steadily. The women huddled with the children beneath a cloth in the brush, crying. Denny worried about an Indian attack.

"It dawned upon me that I had made a desperate venture," Denny later wrote. "My motto in life was to never go backward, and in fact if I had wished to retrace my steps it was about as nearly impossible to do so if I had taken the bridge up behind me."

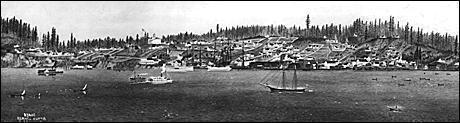

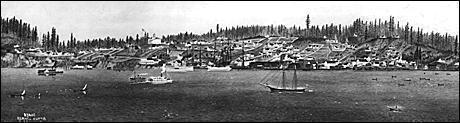

Seattle 1874: By the time of this 1874 painting, Seattle had a railroad, a coal industry and 1,100 residents.

|

|

But after a few weeks, as the party was finishing their first crude houses, they got what most every newcomer craves: work. Capt. Daniel S. Howard of the brig Leonesa asked if the party could provide him with logs to take to San Francisco. The party cut trees near the water and, working at first without oxen, hauled the logs by hand.

Thus began the region's wood-products industry, a natural outgrowth of the 200-foot-tall trees that crowded Puget Sound's shores.

The following February, Denny, William Bell and Carson Boren sounded Elliott Bay with a clothesline and horseshoes.

"After the survey of the harbor," Denny later wrote, "we next examined the land and timber around the Bay, and after three days careful investigation we located claims with a view of lumbering, and, ultimately, of laying off a town."

"You've got to remember that Arthur Denny was a surveyor," said Brewster Denny, his great-grandson and founder of the University of Washington's Graduate School of Public Affairs. "He was a person that was very conscious of the dimensions of land and its utility and what it could be used for."

In just a few years, other pioneers built lumber mills around the Sound, including Henry Yesler's first steam mill in Seattle, at what is now Yesler Way and First Avenue South. Still, the city's fate was not cast simply by having trees and water, Meinig said. The California Gold Rush and the demand for lumber spawned mill towns throughout the Sound in places such as Port Madison, Port Blakeley, Port Gamble and Port Ludlow.

"Seattle's specific site is not anything really special," Meinig said. "It's the Seattle leadership. Why that develops there and not elsewhere I don't know."

"It's a combination of geography, the natural-resource base," said Leonard Garfield, director of the Museum of History & Industry, "and the kind of people who came here."

Seattle 1919: For years, the Smith Tower was the tallest building west of the Mississippi.

|

|

In 1873, Seattle offered a tidy pile of cash and land to entice the Northern Pacific Railroad to build a terminus here. The Northern Pacific chose Tacoma instead. Undeterred, citizens in 1874 took to building a railroad themselves to Walla Walla. It didn't get far, but James Colman, a Scottish businessman, later built the road out to coal deposits in southeast King County, giving the region its leading export for the next 10 years.

Roger Sale in "Seattle: Past to Present" says "the little railroad" and the coal mines, along with the creation of the Dexter Horton Bank and the securing of the University of Washington, was the beginning of the city's economic independence and the sign of "an embryonic city doing all it can for itself."

By 1880, the city had only 3,553 people but had a range of businesses that included meat packing, furniture making, shipbuilding, foundries, breweries, retail stores, banks, law offices and doctors. Tacoma and the Northern Pacific was finally connected to the rest of the nation in 1885, but James Hill's Great Northern Railway arrived in Seattle in 1893.

Word of Klondike gold

Then, in the summer of 1897, 68 men steamed into town with more than a ton of gold and word that they had found it on the Klondike. In a bit of historic irony, their ship was named for Seattle's chief rival, Portland.

"With the arrival of the Portland would come unprecedented prosperity to the Pacific Northwest and the beginning of Seattle as one of the major seaports of the United States," wrote Gordon Newell in "H.W. McCurdy's Marine History of the Pacific Northwest."

Seattle 1958: By now, the city's hills have been regraded and a viaduct runs along the waterfront.

|

|

| THE SEATTLE TIMES |

Seattle had a clear advantage as a gateway to the Klondike. It was the closest major port in the United States. It quickly led to the sheltered waters of the Inside Passage. And it had transcontinental rail service.

Other cities — Tacoma, Portland, San Francisco and Nanaimo, British Columbia, — could make claims as good jumping-off points.

But as Murray Morgan noted in "Skid Road," his celebrated "informal history" of Seattle, the city had "the good fortune that Erastus Brainerd was in town and without a job to keep him busy."

Brainerd, a publicist and newspaperman, chaired the Chamber of Commerce's Gold Rush trade committee. He used the Associated Press and his extensive East Coast newspaper connections to blanket newspapers with booster stories and ads touting Seattle as the essential starting point for the gold fields. He wrote personal letters to every state governor and the mayors of every town with more than 5,000 people. He sent a special Klondike edition of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer to every postmaster and library in the country and to some 5,000 public officials.

Brainerd also persuaded the federal government to open a gold assay office here, ensuring that vast amounts of capital came into the city. By 1904, the office had cleared more than $174 million.

Thousands of people came. Commerce blossomed, real-estate values went up, newspaper circulation increased and ships sailed full. In 1900, the year after Arthur Denny died, the city's population topped 80,000. Ten years later, it hit 237,194, passing Portland.

Rivers made Portland

Carl Abbott stood on the back patio of the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry and looked out at a succession of bridges spanning the Willamette River as it cut through Portland on its way to the Columbia.

"The rivers made Portland," said Abbott, a professor of urban studies and planning at Portland State University. "This particular site on the Willamette River and the early settlement on the Willamette is the first settlement in the Northwest."

Portland and its hinterlands were a fitting final target for the Oregon Trail: temperate, lush and capable of growing most every crop that early settlers once grew back East. The Columbia River had cut a notch through the mountains, clearing a nearly level path for future barges and trains.

But around the turn of the 20th century, some very clear differences between Portland and Seattle emerged. Portland was pioneer stock and old money built on family farms and bulk natural resources shipped out from the Columbia Plain. Seattle was aggressive and progressive and enterprising. Meinig, in his third volume of "The Shaping of America," sees the difference in how the two cities celebrated the dawn of the last century:

"Portland's new-century extravaganza, the Lewis and Clark Exposition (1905), called attention to a distinguished past, whereas Seattle's Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition (1909) looked forward and outward."

Seattle 2001: At 150 years, the Emerald City has become the Pacific Northwest's preeminent metropolis.

|

|

| BETTY UDESEN/ THE SEATTLE TIMES |

Portland, said Abbott as he drove about the city recently, was too satisfied with its accomplishments by the turn of the century to take on Seattle's entrepreneurial zeal.

"They were rich already," he said. "In a sense, Portland was blessed by geography so it didn't have to worry about one more gold rush."

That continued into the middle of the 20th century as Seattle made several key decisions that locked up its role as the Northwest's major city. Both cities prospered during World War II, Portland with the shipbuilding of industrialist Henry Kaiser, Seattle with Boeing airplanes. But where the market for ships fell after the war, air travel sustained Boeing.

Meanwhile, Portland continued to play the safe bets while Seattle took several entrepreneurial risks.

Portland in 1959 launched the Oregon Centennial Exposition with a paltry $2.6 million budget. Writing in "Greater Portland: Urban Life and Landscape in the Pacific Northwest," published this spring by the University of Pennsylvania Press, Abbott said the exposition was "little more than an interminable county fair without the plum preserves and Future Farmers."

Seattle, following up on the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, sold itself as gateway to the Orient and the future with the 1962 World's Fair, officially titled the Century 21 Exposition. City, state and federal funding topped $31 million. The city got a Space Needle. Nearly 10 million people visited.

Portland upgraded its maritime facilities in the '50s and '60s, but with far less funding than consultants suggested. Money went toward nets and pallets and bulk wheat — and not containerized cargo. Seattle in 1963 spent $100 million to modernize and upgrade its terminals, taking direct aim at business going to the ports of Portland and Oakland, Calif.

Seattle passed Portland in the value of import and export trade between 1967 and 1977, said Abbott. In 1970, a consortium of six Japanese shipping lines made Seattle their first port of call on the West Coast.

Seattle expanded its airport and aggressively pursued new routes, doubling Portland's air passenger miles by the early 1980s. Finally, said Abbott, the University of Washington made a play in the 1950s to get a larger share of federal research funds in medicine and the sciences. Enrollment doubled to 30,000 by 1968.

Attributes of Portland

Many people still think of Portland as the more livable city.

"Don't forget that modern Portland, the Portland of say the last 25 to 40 years, has done a much better job of urban planning and transportation and is preserving the beauty of the area even though it's not as beautiful as this one," Brewster Denny said.

But Abbott notes that Seattle outranks Portland in the volume and value of overseas trade, direct overseas flights, foreign-bank offices, foreign investment and foreign-born residents. He sees a symbol in Portland's Kenton neighborhood, where a 35-foot tall Paul Bunyan statue stands at the intersection of North Denver and Interstate Avenue. It was built in 1959 to greet visitors to the Oregon Centennial Exposition.

"It's no Space Needle," Abbott said. "That's for sure."

Eric Sorensen can be reached at (206) 464-8253 and esorensen@seattletimes.com

|

Sunday, November 11, 2001 - 12:00 a.m. Pacific

Sunday, November 11, 2001 - 12:00 a.m. Pacific