|

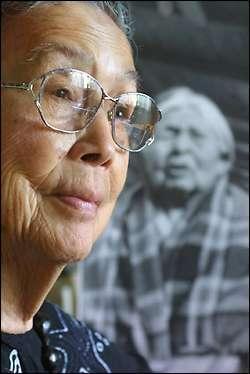

JIMI LOTT / THE SEATTLE TIMES

|

| Vi Hilbert, an Upper Skagit elder, recalls stories of her main inspiration, her aunt Susie Sampson Peter, who is pictured in an old photograph behind her. Hilbert has dedicated most of her life to preserving Lushotseed language and culture. |

Vi Hilbert's birthday party is a big deal every year. Some of her friends schedule their vacations so they can come; others fly in from all corners of the world. They pay their respects by sharing the only gifts Hilbert will accept: stories and songs.

Hilbert is an Upper Skagit elder who has spent the bulk of her adult life researching, documenting and translating the ways and words of Lushootseed — the culture and language of Puget Sound's indigenous people. In the process of preserving her own culture, she's become a bridge to the non-Native world, traveling the country and the globe to tell her ancestors' stories.

Hundreds of Hilbert's friends and family will begin gathering on the Swinomish Indian Reservation near LaConner today for a four-day celebration. The annual "Coming Together Gathering" will honor Hilbert, who turned 83 Tuesday, with stories, song and food.

"She gives and gives and gives in terms of her time and knowledge, and her birthday is an example of that," said Bruce Miller, a Skokomish cultural preservationist and spiritual leader who studied under Hilbert. Miller explained that at "Indian parties" it's the host who gives gifts, though not necessarily material ones. "She feeds them with more than food — she feeds their spirits with praise, respect and recognition."

When Hilbert first started her work, many of her own people criticized her: They said whites had already stolen so much from Indians, and she was giving away what little remained. Her most vocal critics weren't even interested in learning the language or cultural teachings.

But the elders Hilbert interviewed, the last of the Lushootseed speakers to remember the stories and ceremonies handed down from their elders, were grateful someone wanted to know what they knew of the old ways.

Now, Hilbert is the elder. She is a small-framed woman who speaks in soft, soothing tones. Her humor, humility and willingness to share her culture with anyone who wants to learn are the gifts she freely distributes.

No one can remember when Hilbert threw her first party. But this year, she has a special gift to share: the book she's worked on for four years with anthropologist Zalmai "Zeke" Zahir, "Names of Ourselves: Lushootseed, Puget Sound's First People," is finally finished.

It's based on the unpublished manuscripts of Thomas Talbot Waterman, an ethnography pioneer who interviewed Puget Sound elders in the 1910s and '20s, collecting from them thousands of place names.

Before the arrival of whites here, "first peoples were taught to memorize every detail of their land," Hilbert said, and Waterman's field work "has stood the test of time." She and Zahir took on the task of connecting the Waterman place names with contemporary landmarks and describing the land in both English and Lushootseed.

This is Hilbert's eighth book, in addition to the two Lushootseed dictionaries she's helped linguists produce. About the newest publication, Hilbert said Zahir "made it his business to go by canoe and discover every place T.T. Waterman's informants told him about."

"This book is incredible. It's a masterpiece, actually. It will live on in the future as a guideline," she said.

Those who know Hilbert know she's not bragging — she is, as she likes to say, "just being honest."

`It's my job to keep it alive'

|

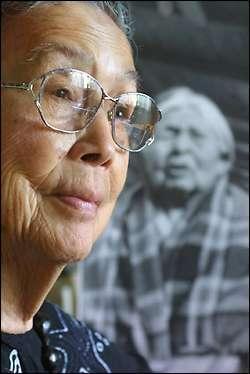

Puget Sound Environmental Learning Center

|

| Hilbert, center, offers a blessing in front of the Puget Sound Environmental Learning Center house post, carved in her image. |

Hilbert grew up on the Skagit River, her family moving wherever her logger father could find work. Her mother knitted socks, picked berries and hops and did whatever else she could to keep the family afloat. But it was the language, the stories and the teachings embedded in them that defined her parents' lives since both were historians for their people.

"My mother had eight children, but I was the only one who lived so I'm responsible for everything," said Hilbert, whose first language is Lushootseed. "All my ancestors were historians, and it's my job to keep it alive."

Hilbert was in her early 40s with a husband and two nearly grown children when she met Thom Hess, a UW linguistics grad student in 1967. At the time, she was a hairdresser with a beauty parlor in her South Seattle home; he was conducting field work with elders, many of them friends and relatives of Hilbert's parents.

Sinks and salon chairs were soon replaced with office furniture, reel-to-reel tape recorders and primitive home computers. Using a variation of the International Phonetic Alphabet — a system of symbols used to record every sound the human voice can make — Hess taught Hilbert to write Lushootseed. Half of all sounds in the language don't have English equivalents.

Then, in 1971, Hilbert suffered an aneurysm and had to re-learn to read and write both English and Lushootseed — skills she quickly re-mastered, said Hess, 64 and now retired from the University of Victoria in British Columbia.

100 hours of tapes

The next year, Hess and Hilbert taught a Salish language class at the University of Washington — and, serendipitously, came into possession of 100 hours of tape recordings that had been in storage at the Burke Museum. Made in the 1950s by Leon Metcalf, a musician and lay anthropologist, the tapes weren't very clear but they included interviews with Hilbert's father and many of her relatives who'd already passed away.

"She would listen to the same stretch of tape over and over, lugging a 25-pound tape recorder over to this cousin's place or that aunt's to get them to help her transcribe," Hess said of Hilbert.

As a result, a huge body of work — individual stories, autobiographies, and people's recollections of cultural and spiritual practices — has survived, Hess said.

"Vi grew up with the language and has the native ear — but it was also her drive, her determination, her belief in the cause that made her unusual," he said.

Hess returned to Canada after the first quarter, convincing Hilbert "she was the only one" who could continue teaching the UW course, even though she'd never been to college herself. Over the next 15 years, a coterie of Hilbert's students volunteered to help her compile her people's history. Some have gone on to teach Salish people how to speak and teach Lushootseed.

Many of her students — and many others Hilbert met along the way — are now her family.

"She is sort of a mother at large. She has a power that doesn't require yelling or demanding, a power that's just there. She is a magnet," said Miller, 57, the Skokomish leader. "She has a world family. Of course she has her own children, but there are countless other people she's adopted, taken in."

Stored in the heart

Katie Jennings, a former public-television producer at KCTS Channel 9, is one of Hilbert's adopted granddaughters. In 1995, Jennings produced a documentary on Hilbert called "Traditions of the Heart"; the title comes from the Lushootseed belief that all cultural learning is stored in the heart, not the head.

"She knows how to look at people and see the wonderful part of them and pull that out," said Jennings, 40, who is white. "She is a light. She always has an encouraging word, and she makes you feel you are the smartest, most wonderful person in the world — who wouldn't want to be around that?"

Hilbert doesn't worry about non-Indians abusing information she shares since they can never fully understand native culture. But "the little bit they get to learn makes them richer, and if they're living richer, it can't help but make the world a better place," Hilbert said. For her own people, Hilbert says it's her responsibility "to pass on what the ancestors realized would make us strong."

And it's Hilbert's mission to leave behind as much as she can — in print and on video and audio tapes.

Her eyesight is fading fast, and she was recently hospitalized for a week. Doctors couldn't find anything wrong.

"The spirit put me down to make me think of what else I have to do, what the rest of my responsibilities are," Hilbert said.

Her list: Have a symphony written ("music is a conductor that has healing power"), catalogue her son's artwork to explain the spiritual practices he depicts, and then archive everything "so it's available for people in the future who are truly interested."

"Then, I think I'm done," Hilbert said. "I'm 90 percent blind now so I have to hurry, hurry, hurry because they tell me the 10 percent is going, going, gone."

Soon, it will be someone else's job to continue what she's started.

In the meantime, Hilbert will celebrate another year of life, another year dedicated to keeping the words and ways of her ancestors alive.

Sara Jean Green can be reached at 206-515-5654 or sgreen@seattletimes.com.

|

Thursday, July 26, 2001 - 12:00 a.m. Pacific

Thursday, July 26, 2001 - 12:00 a.m. Pacific