|

|

|

| Your account | Today's news index | Weather | Traffic | Movies | Restaurants | Today's events | ||||||||

|

|

Sunday, June 27, 2004 - Page updated at 10:06 a.m.

Foreign agriculture bruising "Grown in Washington" label

Seattle Times business reporter CHINCHA ALTA, Peru — Tomasa Magallanes stands at a conveyor belt in a chilled building 10 hours a day, six days a week, stuffing asparagus into cans — and dreaming of a sofa. She is paid just $7 a day, but it is enough to help lift her family above the poverty line toward a better life. And she enjoys more job security since Del Monte, one of the largest U.S. vegetable packers, moved its entire asparagus operation here last year. "We have enough money to eat," says the 42-year-old mother of five. Now she wants more: a college education for her youngest son, and a sofa to replace the hard bench in her small adobe hut. Five thousand miles north, a flatbed truck pulls up to Eloy Valdez's brick rambler in Toppenish, Yakima County. It's around back, Valdez tells the driver. Near the hole in the fence. Valdez, 44, used to live with his wife and two youngest daughters in a five-bedroom, white stucco house with a red tile roof and a hot tub — a lifestyle supported by jobs at the nearby Del Monte asparagus cannery. But those jobs vanished last year when Del Monte contracted with Tomasa Magallanes' factory in Peru to do work once done in Washington. The Valdezes, who had been at Del Monte 18 years, lost their house, filed for bankruptcy and moved to a modest two-bedroom rambler. They kept the hot tub, a vestige of a more luxurious life.

Now even that is gone, sold for $400 and hauled away on the back of the flatbed truck.

Gains outpace losses in intertwined economy It is tempting to see only winners and losers in the shifting fortunes of the global economy. Valdez could be a Boeing machinist, Microsoft code writer, garment maker or call-center receptionist. All are seeing jobs wash offshore to Asia, Africa and South America. The outflow provides work for Magallanes and others in developing countries, helping them eat better food, buy televisions, even surf the Internet at corner shops.

It also provides wealth for corporations that own the fields and factories — and for their investors. But critics say that prosperity is bought by pitting workers like Valdez and Magallanes against each other in what independent presidential candidate Ralph Nader calls a "race to the bottom."

American voters will weigh in this fall as job security and wages promise to be an issue in the presidential race, prompting a war of bumper-sticker rhetoric. But bumper stickers and sound bites miss the bigger picture. Pull back, and the global economy can be seen as more than a job-for-job tally of winners and losers. First, shifts in fortune don't just go one way. For every Valdez who loses a job, shipping crews, truckers and customs inspectors are employed to bring Del Monte's cans from Peru to the world. Second, job shifts are taking place in a growing economy. If outsourcing really were a zero-sum game, the U.S. job market would have shrunk over the past few decades, and unemployment would be constantly rising. Neither is the case. Overall U.S. employment has climbed 46 percent since 1980, far outpacing a 24 percent rise in population — and despite a 20 percent drop in farm jobs.

Finally, trade allows specialization. Farmers make food, not tractors. And tractor factories don't grow food. This process, known as comparative advantage, lets countries make what they make best and trade for what they need, creating a rising tide of wealth.

In the past decade, comparative advantage and trade have stuffed U.S. grocery shelves with year-round abundance — from Chilean grapes to Thai basil — at the lowest prices in history. They have opened foreign countries to McDonald's French fries and Microsoft Windows. And they have generated new sales and jobs at both ends of the transaction. During the 1990s, as the U.S. economy soared, Peru's exports doubled. That poured billions of dollars into Peru's economy, helping provide schools and medical care for impoverished families. Even accounting for the recent U.S. recession, the world economy has grown 9 percent in the last five years, while the U.S. economy has grown 19 percent, according to the World Bank.

A window on farming

To see the global economy at work, consider asparagus.

And asparagus production is shifting overseas fast. In Washington, the nation's second-largest asparagus producer after California, 60 percent of the asparagus fields — nearly 17,000 acres — have been plowed under since 1991, when the U.S. signed a trade agreement that dropped tariffs on farm imports from Peru and other Andean countries.

Last year, Del Monte shut its asparagus operations in Toppenish, and Chiquita shut a plant in Walla Walla. This month, Green Giant, owned by General Mills, said it will close its massive plant in Dayton, Columbia County, next June.

Other Washington-grown crops are at risk. Apples, grapes and potatoes are grown more cheaply in Latin America and China. U.S. citrus fruits, artichokes and avocados are headed the same way. The threat "is broader than asparagus," says Charles Brown, a lobbyist who has represented asparagus interests in the Legislature. "It is industrywide."

That was underscored two years ago at a trade reception in Seattle when Peru's first lady, Elaine Karp, told Brown, "By the way, we know how to make dehydrated potatoes in Peru as well."

Prosperity flows, but some left high and dry For Peru, where nearly half of its 28 million people live on less than $2 a day, opening the U.S. market to asparagus has lifted 50,000 farmworkers from subsistence into a formal economy of wages and benefits. Peru feels that impact even though economists estimate 67 cents of every dollar U.S. shoppers spend on Peru's asparagus stays in the U.S., supporting a delivery infrastructure of airplanes, pilots, customs clearance, trucks and truckers, grocery clerks, computers and more. Seen that way, free trade serves another popular sound bite: "All boats rise." The problem is Eloy Valdez's hot tub. The wealth generated by trade doesn't make his pain any less real. "Globalization has created a better life for millions of people, " says Carlos Arrese, general manager at Agrokasa, Peru's largest exporter of fresh asparagus. "But somebody has to pay the bill." In their own way, even Eloy and Amelia Valdez are complicit in the pain-and-gain of free trade. They shop at Wal-Mart, where they take advantage of the famous low-low prices on products shipped in from around the world. Their loss as workers can't be separated from their win as consumers. Jane Vance, 80, counts herself a winner. She and other residents of a Seattle retirement home buy asparagus at Bartell Drugs for 99 cents a can. She didn't notice it came from Peru. She just liked the price, and the quality. "I love it," she says. And, 5,000 miles to the south, Vance's choice is helping keep Tomasa Magallanes employed. At the spotless factory outside of Chincha in southern Peru, Magallanes steps away from the conveyor belt and pulls down her surgical mask. She knows the cans she packs go around the world. Beyond that, she knows little of the complexities surrounding globalization. She just knows what it takes to buy a sofa. "Del Monte asked for quality, and we make sure they get what they want," she says.

Fallout from policy

How asparagus shifted to Peru is a quirky tale, but typical of the way trade agreements can suddenly shift an industry offshore. Remember the cocaine-caked 1980s? Nearly all of the drug consumed in the U.S. came from coca plants grown in the mountainous Andean countries of Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia and Peru. In 1991, Congress sought to stamp out coca cultivation by encouraging alternative crops in those countries. The Andean Trade Preferences Act (ATPA) eliminated a 21 percent tariff on asparagus and other crops.

The policy didn't stamp out coca, which still thrives in Peru's inland jungle. But it did create legitimate farm and factory jobs along the coast — and began stamping out U.S. asparagus farms.

One U.S. program helped set up an early farm in Peru in 1986. But most of the money to build Peru's asparagus industry came from Peruvian entrepreneurs. Instead, it was U.S. farmers who had been subsidized before ATPA — through the tariff on foreign asparagus. "A tariff represents a domestic subsidy to our producers and a tax on our consumers," says Larry Fuell, former agricultural attaché to the U.S. Embassy in Lima. "Its removal does not constitute a subsidy to foreign producers."

This year, Congress ignored demands to have the asparagus tariff restored. It is bypassing contentious World Trade Organization talks to set up "free trade areas" modeled on the NAFTA accord with Mexico and Canada.

Irrigation project brings Peruvian desert to life Peru proved fertile ground for asparagus. All it took was water. In a project on the scale of the Grand Coulee Dam, the Peruvian government erected Chavimochic, a $1 billion, 110-mile concrete canal that carries glacial water from the Andes to irrigate a vast coastal desert. Before Chavimochic was built 15 years ago, the coast was mostly a moonscape of dunes dotted with scrub brush and rocks; fewer than 1,500 acres were planted in crops. Now many of the dunes have been flattened into fields and laid with irrigation hoses. Today, there are 345,000 acres of fields growing asparagus, sugar cane, citrus, mangos, artichokes, avocados, peppers and onions. The desert sand provides a soft base for delicate asparagus spears, while the warm, rainless coastal climate enables farmers to control moisture and fertilizer. Here asparagus can grow an inch an hour during the hot season, requiring up to four cuttings a day as shoots reach their full height of 8 to 10 inches. Each field produces twice a year, compared with once in Washington. Plants produce three times as much asparagus as those in the U.S. The reverse seasons in the Southern Hemisphere are a plus. Peru's fields are in their prime during the winter holidays in the United States. The scale of growing is staggering. A big asparagus farm in Washington is 500 acres. In Peru, a typical operation, Sociedad Agricola Viru, cultivates 1,235 acres. It is one of 53 growers in the area, and not the largest. Today, Peru has 47,500 acres of asparagus, compared with 33,000 acres in Washington at its peak in 1989, a figure that fell to 13,200 acres this year. Viru also grows onions and peppers to lessen the reliance on asparagus. Growers worry that overproduction could drive world prices down. But so far, increased supply has simply fueled demand. Since 1990, the average American has tripled consumption of fresh asparagus to about a pound a year, and prices are up 40 percent, to about $1.25 a pound wholesale, according to the Agriculture Department and the General Accounting Office. Viru's owner, Miguel Nicolini, started the farm just 10 years ago and has since built two canneries. In the busy season, 3,000 workers clean, sort, cut and can asparagus in two shifts, handling the harvest of 1,300 field workers. Last month, he was in Minneapolis to sign a contract to produce canned asparagus for Green Giant starting next year. It's the same contract that now is filled in Dayton, Wash.

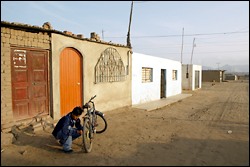

Prison or progress? From the outside, the factory where Magallanes works could be mistaken for a medium-security prison. Barbed wire stretches along high concrete walls. Guard turrets stand at the corners. Sentries man the thick steel doors. Most of Peru's factories look this way, and it would be easy to think Magallanes works in a labor gulag at the edge of a slum. The 130,000 people in Chincha Alta live in a world of unpaved streets, windowless huts and open sewers. Peru's infant-mortality rate is 30 per 1,000 births, more than four times the worldwide rate. But in fact, when Agro Industrias Backus built the plant in 1990, it was fortified against Peru's Shining Path terrorists, a Maoist group that attacked factories as symbols of capitalism. Reforms in the past decade have seen terrorism largely extinguished, making way for Del Monte, Green Giant and other big buyers. Inside the factory's high walls, the lawns are manicured; new brick buildings house a cafeteria and changing rooms for workers. To enter the giant cannery room, Magallanes washes her hands with sterilizing soap and walks through pools of bleach to disinfect her shoes. Pickers wash just as thoroughly before entering the fields. Trucks drive through bleach or have their tires sprayed. Safeguards like these help farms and factories throughout Peru meet strict sanitary rules for the U.S., Europe and Japan — another ripple effect of global trade. Trade's impact can be seen clearly in Peru's economy. Over the past decade, the country's annual output grew by half to $56 billion. Exports more than doubled, to nearly $8 billion, according to the World Bank. And agriculture, led by asparagus, was the fastest-growing part of the economy, expanding nearly twice as fast as manufacturing. Last year, asparagus overtook coffee as Peru's top export crop and accounted for roughly a quarter of the country's farm exports. At peak season, 800 people work at the Backus cannery full time. One in 10 cans carries the Del Monte label.

Home life Factory jobs have lifted thousands in Peru out of the informal economy of subsistence farming in the mountains or selling trinkets on Lima's streets. At Backus, Magallanes is in the formal economy, with steady wages, a bank account, government health care and a pension. "It changed the whole region by providing employment," says Jorge Fernandini, president of the Peruvian Institute for Asparagus and Vegetables. Those gains can seem small by the time they follow Magallanes home. She and her family live in a single-story hut, along a dirt road, on the outskirts of Chincha. Built 20 years ago with help from a Canadian priest, the adobe walls are crumbling, creating holes big enough for a large dog to wiggle through. A pit toilet in the back yard is sheltered by reed mats. The front window is fitted with patterned cinderblock, not expensive glass. A red cotton cloth is tacked up as a curtain. Magallanes and her husband, Juan Alberto Garayar, a construction worker, each work six days a week, typically 10 hours a day, to bring in 600 soles a month, about $2,200 a year, above the national average of $2,050. It is Magallanes' cannery job that has made that difference. Her husband's work is not as steady, and her former job at a garment factory paid less. The couple now have the means to fix the walls. Bricks and sand clutter the living room, and they've torn down one wall already. The finished walls are plastered smooth and painted green or yellow. Rather than money, the project "mainly depends on my husband," Tomasa Magallanes says with the smile of a spouse. "He builds it in his spare time." The furnishings are few: a table, two benches, three beds. But there is running water, a refrigerator and gas stove, two TVs and a DVD player — relative luxuries. "I want to see my house nicely decorated and to have more comfort," Magallanes says. "We have some things, but I still would like to have a little more furniture — a sofa set." Magallanes' own parents made a meager living raising cotton on a small parcel of family land. She left school after eighth grade. Now she is sending two of her younger children to a private school. She paid for the oldest, Juan Pablo, to attend a four-year technical institute to become a computer technician. But he quit when his girlfriend became pregnant, and now drives a taxi. Hopes for the future have shifted to the youngest boy, Andy. He is in eighth grade and wants to become a mining engineer, like one of his father's friends. The other children worked in the factory during vacation and holidays. "But I don't want Andy to go through that," Magallanes says. "He has to study so he can have a better job and career and make more money. He'd be the only one."

Tariffs work both ways Just as the global economy can be seen at work in a can of asparagus, so it plays out in the red cloth that covers Magallanes' cinderblock window. Pima cotton was for a long time Peru's prize crop, known worldwide for extra-long, silky fibers. But if the curtain in Tomasa's hut was made after 1990, it is likely to be of U.S. cotton. That's when Peru dropped the high tariffs it had used to keep foreign cotton out and protect its own farmers. Today, Peru imports nearly half of its cotton, up from none in 1990. Textile mills in Lima are being converted to handle short-fiber U.S. cotton. Peruvian cotton farmers have plowed under more than half their acreage, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Production has dropped by more than 40 percent. Sound familiar? It's the same thing that happened to U.S. asparagus. Asparagus production in the U.S. has risen just 4 percent since 1993, but imports have more than doubled. Exports, meanwhile, have fallen 24 percent. Now cotton farmers in Peru, just like asparagus farmers in the U.S., want those tariffs back. Earlier this month, after the Green Giant announcement, U.S. Rep. George Nethercutt Jr., R-Spokane, who is running for Senate, asked for a federal investigation of the asparagus situation. "Trade policy should help open markets to our farmers, not push them out of production," he said. That may win farm votes. But it ignores the complexity of a global economy. Restoring tariffs would ricochet well beyond the farm industry because countries often retaliate against each other by adding tariffs to other products. Microsoft-powered computers at the Lima airport and the Backus plant could disappear if Peru imposed a duty on tech imports and refused to protect the software from piracy. Nextel cellphones, ubiquitous in Peru, might disappear for the same reason. Drug makers might lose protection against generic copies in Peru. Along busy streets, bright signs for Coke, Pepsi, Citibank, Bell South, Papa John's, KFC, Marriott — even Starbucks — could vanish if Peru chose to clap tariffs on those products. The ricochet would bounce all the way back to Washington, which bills itself as the most trade-dependent state in the nation. The state says one in four Washington jobs is tied to the $100 billion in goods that pass through its ports each year.

Moving down, and up As fortunes shift in the global economy, individuals must shift with them — or be left behind. Eloy Valdez grew up in Toppenish with 11 brothers and sisters in a two-bedroom house. His father came from Mexico in 1938 to work in the fields. As a young man, Eloy Valdez drove tractors and picked fruit. Then he landed a job at Del Monte, where he worked as a mechanic for 18 years. His wife, Amelia, 43, worked there 11 years filling cans. They raised four daughters and, over time, saved to buy the five-bedroom stucco house, complete with hot tub. Valdez tells his story with the pride of someone who worked his way up from the bottom. His job at Del Monte paid $13.85 an hour; Amelia made $11. From the new house, they would travel past tidy, modest homes and the rodeo grounds to reach the cannery. But two summers ago, Del Monte cut back their hours. The Valdezes couldn't make the $1,200 monthly mortgage payments. They filed for bankruptcy and lost $20,000 in equity when they gave the house back to the bank. Then last October, they lost their jobs. They had to start over, looking for work in a changed economy. Eloy Valdez got an interview at Wal-Mart's distribution center in Grandview for a job that started at $10 an hour. A few days later, the manager called and said Valdez was overqualified because he was a certified forklift driver. He knows the man who got the job, an immigrant. "He took $8 an hour," Valdez says. "I think it was those two dollars" that made the difference. The two oldest Valdez daughters are married and on their own. The two youngest live at home. While the couple were unemployed, their 15-year-old daughter helped put food on the table by mowing lawns and baby-sitting. Their 21-year-old daughter works full time and wants a life away from the fields. She is studying dental hygiene at Yakima Valley Community College. In February, Eloy Valdez found a job driving trucks for $9.25 an hour for a plant near Yakima. His wife was hired to work in the factory. They work different shifts; each commutes 60 miles a day. The company, Alexandria Moulding, is itself international. Based in Canada, it has two U.S. locations and sells worldwide. Valdez says he bears no ill will toward the Peruvians who have absorbed the better-paying job he lost. "I figure everybody's got to eat," he says. Back in Peru, Tomasa Magallanes has enough to eat. What she wants now is a sofa. Alwyn Scott: 206-464-3329 or ascott@seattletimes.com. Irene Keliher and Meylin Zink Yi served as Spanish interpreters in Peru.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

seattletimes.com home

Home delivery

| Contact us

| Search archive

| Site map

| Low-graphic

NWclassifieds

| NWsource

| Advertising info

| The Seattle Times Company