Originally published November 28, 2014 at 12:03 PM | Page modified December 1, 2014 at 3:53 PM

Landslide survivors find gratitude and ways to go on

Still lost and mourning, survivors of the landslide along Highway 530 find strength in the kindness of others and among themselves.

Seattle Times staff reporter

MARCUS YAM / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Members of the Brooks family of Arlington embrace during a prayer service in April at Haller Middle School in Arlington, one of many community gatherings to show support and gratitude in the aftermath of the Highway 530 mudslide. From left are Kelly, Logan, Dane and Gwendolyn Brooks

MARCUS YAM / THE SEATTLE TIMES

A candlelight vigil dedicated to the communities affected by the Highway 530 mudslide brought hundreds of people to the Darrington Community Center in April. Prayer has played a central role in the recovery of this community (population 1,362) where churches far outnumber taverns.

MARCUS YAM / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Heart-shaped cards with messages of love, loss and hope for the victims and communities affected by the massive mudslide decorate a broken-heart-shaped paperboard at the IGA supermarket in Darrington in April.

Alan Bejvl, 21, shown wearing his favorite hoodie, and fiancee Delaney Webb, 19, were planning their August wedding at her grandparents’ house when the slide hit. The hoodie was recovered in the debris, as was his prized pickup truck. His older brother salvaged parts from the truck to build a replica in Alan’s honor.

MARCUS YAM / THE SEATTLE TIMES

After the funeral for Linda McPherson, a mudslide victim, residents came together for a meal at the Darrington Community Center. The meals are a community tradition, and a testament to the closeness of the people who live here. At bottom left is Linda’s husband, Gary “Mac” McPherson, wearing a baseball cap.

MARCUS YAM / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Jeff and Jan McClelland, both volunteer firefighters at Fire District 24, were the first official responders on the scene of the Highway 530 mudslide. The Darrington couple worked side-by-side with families and other volunteers to recover bodies from the mud, and remain grateful for the friendships forged during those grueling days.

MARCUS YAM / THE SEATTLE TIMES

On April 2, FEMA workers stand beneath an American flag flying at half staff in the debris field of the Highway 530 mudslide, west of Darrington. The large flag, raised on the third day after the mudslide, replaces an older flag found in the debris field and raised at half staff by the Oso Fire Department on the second day.

MARCUS YAM / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Just days after the deadly slide, Pastor Mike DeLuca speaks to reporters at Darrington Fire Station 24 after saying a prayer and observing a moment of silence for mudslide victims. DeLuca, pastor of Darrington’s First Baptist Church, spent months giving away thousands of dollars to victims. Baptists from around the world inundated the community with donations.

MARCUS YAM / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Congregants of Darrington’s First Baptist Church exchange greetings during Sunday service April 6. The slide closed a stretch of Highway 530 for weeks, making it difficult for worshippers from Arlington to go to church. Some drove four hours round trip to attend Easter services, the church’s first post-slide service as a community.

MARCUS YAM / THE SEATTLE TIMES

DeLuca sings a hymn at the First Baptist Church in Darrington, where he has been a pastor for 38 years. DeLuca, an avid photographer, stopped taking photos for months after the slide. “I think it’s because I don’t want to remember this part of my life,’’ he says. But he’s begun taking pictures again, grateful for happier times.

MARCUS YAM / THE SEATTLE TIMES

DeLuca stands beside a Columbarium, an intended memorial erected at the Darrington Cemetery to honor the mudslide victims. The memorial was covered with a metal plate this past August to respect privacy concerns.

MARCUS YAM / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Wendy Wagner watches the water levels of the Stillaguamish River rise along Highway 530 in March. The mudslide changed the course of the river and of the lives of the people living along it. In the months that followed, they have been quietly putting their lives back together.

MARCUS YAM / THE SEATTLE TIMES

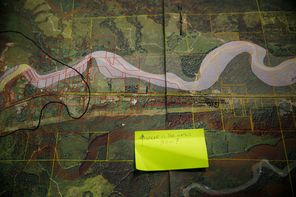

Red markings on a map show the path of the north fork of the Stillaguamish River and the landscape around it where the Highway 530 slide occurred. The map was displayed during a community meeting in Darrington days after the slide. The note is from someone inquiring about the state of flooding that day.

MARCUS YAM / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Pastor Mike DeLuca, left, says a prayer as rescue workers and community members gather outside the Darrington Fire District 24 station one week after the slide, on March 29. DeLuca has been a central figure in the long-term recovery effort.

MARCUS YAM / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Jeff and Jan McClelland, both volunteer firefighters at the Fire District 24, tend to goats on their farm, west of Darrington. The couple worked to rescue people and recover bodies in the weeks after the slide, and forged close ties with the brothers of Steven Hadaway, who was killed. The brothers call the couple regularly to express their love and gratitude.

Oso landslide: Comprehensive coverage of the March 22 disaster and recovery

The Seattle Times

A collection of stories and visuals about the disaster, why it may have happened and the people it affected.

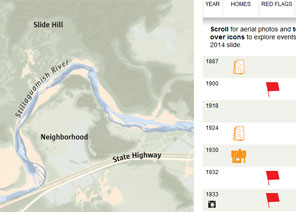

Interactive: Building toward disaster

THE SEATTLE TIMES

Use an interactive to see how, even as warnings mounted, homes kept being built in slide-prone Steelhead Haven.

Remembering the victims

Compiled by The Seattle Times

Read about the lives of the victims.

Interactive map: A detailed view of the neighborhood hit by the landslide

Garland Potts, Cheryl Phillips / The Seattle Times

Use an interactive tool to see the landslide’s deadly path.

TIMES WATCHDOG

![]()

Alan Bejvl loved a good joke.

He was, his grandfather says, “the bubbles” in the family, the one who could make every gathering sparkle with laughter.

So it was no surprise to his mother, Diana Bejvl, that her son would find a way to make her laugh even as she contemplated his death.

It was May 31, more than two months after a hillside along Highway 530 collapsed into the north fork of the Stillaguamish River with enough force to bury a mile-square swath of land under 80 feet of muck in about two minutes.

The bucolic neighborhood of Steelhead Haven was swept away, and 43 people were killed, making the 530 slide between Oso and Darrington the deadliest in U.S. history.

Alan, 21, and his fiancé, Delaney Webb, 19, had been planning their wedding at her grandparents’ house near the river the morning the slide hit. No one had heard from them since.

Searchers had already found the remains of Alan’s prized pickup when Diana Bejvl visited the site with other families. She was standing near the mangled remains of his truck when her eyes spotted a fleck of orange on a tree stump.

“What is that?” she asked.

Her daughter made her way to the stump and lifted the object. Diana’s eyes widened.

“Are you kidding me?!”

It was Alan’s favorite hoodie, the dark blue one with the orange Tootsie Pop and the words “How Many Licks Does It Take?”

Bejvl recalled the pleasure that ridiculous hoodie gave Alan. The number of jokes it generated. How much grief he got for it. And then she laughed.

“In all that mud, there’s that one thing that would make me laugh,” she says, brightening at the memory. “That’s not coincidence. That’s Alan giving me something to laugh at.”

Bejvl didn’t expect to find gratitude on a tree stump, but that’s what happens sometimes when your world shatters; when you lose a child and mourn a future that will never be.

It’s what happens sometimes when you’re feeling lost and weary from tending to all the mundane things required to put one foot in front of the other when your heart is broken. When you tell people you’re fine, when what you really mean is that you’re FINE: “Freaked out. Insecure. Neurotic. Emotional.”

Bejvl says she’s all those things. And, yet, talking about Alan and the overwhelming kindness of friends and strangers — the gifts small and large that make it possible to go on — opens up a space for light, she says.

Alan died at the peak of his life, when he was full of optimism and crazy in love with Delaney, who was found within two feet of him.

“I picture them in the house, probably in the kitchen,’’ she says. “He died happy.”

The day of the slide, Bejvl had made him chicken enchiladas — his favorite. He knew he was loved.

Even the manner of his death seemed fitting for a man whose favorite motto was “Overkill is underrated.”

“Of course he would die in the biggest landslide in state history!” Bejvl says, laughing.

She finds gratitude in friends who took days off work to sit with her husband so he wouldn’t be alone, and who traveled from Boise, Idaho, to Darrington to console her eldest son. She finds it in the couple who drove from Sumac to give her money, in the AT&T representative who accessed Alan’s cloud account and downloaded photos that would have been lost to her

She’s grateful for a hoodie she can hold. Grateful she can help tutor math this fall; grateful she can honor Alan by helping others.

“Alan would willingly sacrifice himself if he knew it would do good in the world,’’ she says. “If I can make one family’s life better, give one child a happier home, there’s nothing that would have made Alan happier.”

She finds gratitude in the courage of the first responders and “the loggers, working in the muck and pulling out their friends and loved ones.”

“How do you thank these people?” she asks. “All you can do is say, ‘thank you’ and hope they realize the depth of meaning and gratitude in those two words.”

---

Volunteer firefighter Jan McClelland had just delivered twin kid goats on her farm when her emergency radio squawked with a call for a single engine: A roof was in the road; they needed someone to get rid of it.

Her husband, Jeff, also a volunteer with the Darrington Fire Department, took the call and drove off. As she cleaned up, Jan grew concerned.

Firefighters from the Oso department were talking about the slide on the emergency radio, and so were the Darrington responders. But they weren’t talking to each other, and it wasn’t clear they could even see each other.

Jan leapt in her car and raced toward the slide, radioing her husband, who told her to bring an aid vehicle and swift-water-rescue gear.

Arriving, the McClellands and friend, firefighter Shaylah Dobbins, donned dry suits, tied up to a rope and made their way in the direction of a man — his arm nearly severed — calling for help.

The trio had no idea what they were walking into. After a false start, they made their way through muck as thick as pea soup, holding medical bags above their heads and hoping they could hang onto their lone radio.

“Every step you took, you had to wait until your foot felt like it was on something really solid because you keep going down, and you didn’t know if you were going to get in a big hole and just keep going.”

After about an hour of climbing and sinking, they reached Mark Lambert, 37, who had landed on an embankment, stripped of everything but his boxers.

“I knew who he was,” Jan says. As they hauled him to a place where he could be evacuated by helicopter, she talked to him, telling him he could come to her farm and see the babies.

They saw him, months later, at a fundraiser to help with his medical bills.

“He was so happy to meet us. We were happy to see him. There were lots of tears.”

The McClellands spent weeks at the slide, searching for victims until their commander pulled them off. Then they’d go to the firehouse where an astonishing outpouring of love awaited them.

“Our building was full of donations. It was so overwhelming, the feelings that gave you, how far some of them traveled because they didn’t want to just send it here. They wanted to look you in the eye and give it to you, so it was all very personal from the get-go.”

There were so many donations that when fires broke out in Wenatchee, the firefighters loaded up a huge trailer with anything they thought would be helpful. “We just kinda called it our ‘pay it forward,’ ” Jan says. “I kinda get emotional when I think about that because that meant a lot to us to be able to do it. Those are the kinds of things that make us grateful that we have the opportunity to help somebody else. Because that’s what we do.”

But the greatest gift to come from the disaster was friendship with the brothers of Steven Hadaway, who was installing a satellite dish on a home when he lost his life.

The official search had been called off before his body was found. But his brothers, John and Frank Hadaway, who live in Pierce County, refused to stop searching. Jan and Jeff told them they’d search with them.

A week or 10 days after the slide, the brothers showed up with 80 pounds of king crab for the rescuers.

“They were just so grateful for, you know, we’re out there alongside them, on our hands and knees, ripping apart whatever we have to, digging to find their brother,” Jan says. “Initially, you poke and hope you’re going to find some sign of life, some miraculous thing where somebody’s in a little cubby hole somehow and gonna be alive. And then we just kept searching, and they just so — talk about gratitude — I mean, they love our bones, do they not?”

“They do,” her husband says.

Once every week to 10 days, John Hadaway sends a message: “Love you and Jeff. We’re going to get up and see you guys real soon. Thinking of you. God bless you.”

Says Jan: “I feel so grateful to have been able to have a great relationship with some very new dear friends.”

---

Pastor Mike DeLuca of Darrington’s First Baptist Church was at the barber’s getting his hair cut when a frantic woman burst in, looking for a working phone. A house was in the middle of the highway, she reported. Three people were injured and one was dead. Others in the shop rushed down the road toward the slide. DeLuca went home and had a cup of coffee.

“I learned early on not to be an ambulance chaser,” he says, recounting the events from his living room in Darrington nearly six months later. He’d been providing spiritual counseling in the community for 38 years; the decent thing, he figured, was to wait for a call.

With phone and Internet access knocked out, it would be a day before DeLuca, 71, learned the magnitude of the disaster.

“People were coming back into town and telling me who was rescued and how they were rescued,” he says. “And it was just by the hands of the people on site, the people who drove up, the people who discovered the slide from either side. They just walked out on the mud, on the logs, and dug with their hands through the muck . . .”

“I began to feel guilty. Here I am at home, drinking coffee, while people are dying. I mean, I just felt horrible that I didn’t go out there.”

He sought counsel from people who had gone to the site. They told him there were only a few survivors and others more able had rescued them. In short, they told him there was nothing he could have done to save anyone.

The pastor wasn’t able to help that day, but he’s spent nearly every waking hour since then trying to help make whole the lives of those affected by the slide, and by extension, his community.

It started three days after the slide, when phone service to Darrington was restored.

“All of a sudden, the phone started ringing, ringing, ringing, ringing from all over the country,” he says. “There were churches, pastors, everybody I knew was calling, wanting to donate.”

The enormous task of giving away those donations fell to him.

He points to a thick white envelope on a desk in his living room. “That white envelope there? Those are the letters of contributions from all over the country that came through our church.” He stops and clears his throat. “That thing was full of checks. Thousands of dollars. I didn’t know what to do with the money. During that period of time, I thought, who am I going to help?”

He gave money to anyone he could find who was directly affected by the slide, he says. In a town of independent people who keep their troubles to themselves, it was a daunting job.

He tracked down people through friends and the Internet, telling them he wanted to give them money. Most people didn’t answer, but when they did, he gave them $1,000 to help with funeral expenses or help get them back on their feet.

He gave $1,000 to the teacher of a first-grade class that had lost a classmate and told them to do something special in her honor. He paid for a bench to go in their memorial garden.

He put his focus on women and orphans after hearing one of his congregants express gratitude that her husband was still alive. But for a last-minute change of plans, the man would have been helping a friend roof a home on Steelhead Drive.

He joined the other pastors from Darrington on the Darrington Long-Term Recovery Group, and when the group merged with the Oso/Arlington group, he was recruited to be its chief facilitator.

The group included pastors, federal and state disaster officials, the Red Cross, Salvation Army, Catholic Charity Services and a host of other organizations that would help identify and fund needs with the millions of dollars in donations and grants available to help people rebuild their lives.

The details were as complex and individualized as the people affected: legal issues, mortgages, college expenses, gas money, down payments on a new house or car.

When they funded a need, DeLuca would lead the cheers, reminding everyone they had made a difference.

“It became so much fun helping people,” he says.

Then in August, DeLuca’s father died. He turned over his leadership in the committee to a priest from Oso whose congregation paid for all the funerals. In September, he and his wife, Karen, drove to California for his dad’s service.

In recent months, DeLuca has found quieter kinds of satisfaction.

He takes out a manila envelope stuffed with letters from the children whose class he gave $1,000. The writing is primitive, the drawings sweet and evocative of the day.

As he reads through the stack, he cries softly, moved and grateful for the gratitude of others.

“Little things like this just bless me,” he says.

Susan Kelleher is a Pacific NW magazine staff writer. Marcus Yam is a former Seattle Times staff photographer.