|

|

|

| Your account | Today's news index | Weather | Traffic | Movies | Restaurants | Today's events | ||||||||

|

|

Tuesday, July 13, 2004 - Page updated at 01:17 P.M. Workplace conditions jeopardize passenger safety, screeners say Copyright 2004, The Seattle Times Company By Ken Armstrong, Cheryl Phillips and Steve Miletich

In Seattle, a screener received a letter of admonishment for this offense: "Hands in uniform pants pockets." A Denver screener says a supervisor repeatedly called him "boy" — and explained it away by saying that where he is from, that's what blacks are called. A Los Angeles screener injured his arm lifting a passenger's bag that held not clothes or toiletries but a small engine block. Some screeners struggle to stay awake while trying to spot weapons in grainy X-ray images. Some get distracted by managers prowling for petty infractions. Some have been fired by mistake, victims of bureaucratic bungling. Morale has suffered, and with it, security. Since the 1970s, the federal government has linked working conditions for screeners with public safety. Time and again, audits have blamed failure to detect guns, knives or bombs on low pay, high turnover, insufficient training and a kind of thankless work that combines tedium with stress.

But the kinds of security lapses that preceded the 2001 hijackings continue. Fatigue, fear and confusion undermine the work of federal screeners, creating a daily risk of another major breakdown. "We've got bad morale and got the seniority thing and vacation thing and rotation thing and promotion thing and this rumor, that rumor. Before you know, your head's swimming in everything but what you're hired to do — and that's security," a Minneapolis screener said. "False promises" An internal TSA memo, obtained by The Seattle Times, chronicles the agency's management failures — and, coming from management itself, helps validate the complaints of screeners to TSA, Congress and others. The Feb. 20 memo was sent to TSA's acting administrator, David Stone, from an advisory council of TSA directors in charge of security at individual airports. It warns that TSA has subjected screeners, "our most valuable resource," to a litany of abuses. TSA forces screeners to sacrifice vacation time "for the good of the agency" but turns around and fires screeners with little explanation, the memo says.

"We expect consistency but provide none ourselves," says the memo, written by council Chairwoman Marcia Florian, who oversees security at the Phoenix airport. "Our screeners have endured false promises from hiring contractors, weeks or months with no (or incorrect) pay or benefits, competency testing, right-sizing, mandatory conversion to part time, forced overtime, and now a recertification process that shows no regard for screener morale, effectiveness, or livelihood," the memo says. More than 100 current or former TSA employees interviewed by The Seattle Times echoed Florian. In stories striking for their similarity — whether their airport is in Los Angeles, Houston, Boston or elsewhere — employees described a workplace defined by intimidation, pettiness and marching orders that fluctuate by supervisor, shift and airport. Without doubt, some TSA workers are quick to complain, call in sick or ignore reasonable orders. But even Stone has told senators that TSA needs to do better by its employees. TSA spokesman Mark Hatfield said that while hiring and dispatching tens of thousands of screeners under tight deadlines, the agency stumbled. He rattled off examples. Workers didn't receive proper credit for previous federal or military service, and he personally went a year before his annual vacation time was accurately recorded. But, Hatfield said, such missteps occurred largely because the fledgling agency needed to borrow a patchwork of support services, with contractors involved in everything from hiring to firing to processing employee complaints. Now, he said, the agency has more people to handle such tasks and is determined to let local directors make key personnel decisions. "We clearly failed in some of the basic nurturing and caring of our work force," Hatfield said. "And I think it's also fair to say that we have made a very deliberate effort and have seen very significant successes in remediating that situation." Without question, the TSA has made some improvements since the days when screeners were hired by the airlines. The pay is better. Workers get benefits. Turnover, though still high, isn't what it was.

The blue-ink rule At TSA, screeners say, it doesn't take much to run afoul of the rules and of certain supervisors. Socks must be black (supervisors can conduct sock checks, ordering screeners to lift their pant legs), and ink must be blue (former Albany, N.Y., supervisor Todd Grandy says a boss "had a conniption" when he used a green pen to make checkmarks on a form). Some managers dictate posture, ordering screeners to keep their hands out of their pockets or to stand at parade rest — hands clasped behind back, feet a foot apart — as though in the military. In Portland, Ore., screeners could not take breaks in the concourse areas unless they wore coats over their uniforms and were there to buy a meal. (A cup of coffee, they were told, would not suffice.) The policy was rescinded only after screeners pointed out how much they spent at airport restaurants. Many screeners interviewed by The Times complained of inexperienced supervisors, leadership by intimidation, and promotions based on favoritism (at least two security directors have lost their jobs over nepotism charges). Most screeners requested anonymity for fear of being fired. But with few exceptions, The Times was able to obtain corroboration from documents or other screeners. One screener provided The Times with love letters from his supervisor — letters with sappy expressions of unrequited affection, with entreaties to pay less attention to co-workers and more attention to him. But the screener hasn't complained. He won't. He's convinced it won't do any good — and, he said, he needs the job. Mismanagement hobbled TSA from the very beginning. TSA began recruiting screeners in March 2002, offering a starting salary of $23,600, with extra pay in areas with high living costs. Before that year was over, 55,600 people were tapped from an applicant pool of 1.7 million, a hiring pace so frenetic that, at times, 5,000 people a week were signed up. To handle recruitment, TSA hired NCS Pearson, a data-processing company that billed the government $740 million, more than seven times its original contract. TSA failed to keep proper tabs on Pearson and other human-resources contractors, creating a host of problems, according to a government audit.

Some screeners say TSA used bait-and-switch tactics. A former Boston screener provided The Times with his hiring letter, which promised pay of $31,200 and included this cheery sign-off: "You should find here a great opportunity for public service and a distinguished career in transportation security." But TSA paid him only $26,800, according to pay records. He complained, he said, only to be told his hiring letter wasn't an official contract. Employee discontent, though widespread, is not universal. "I enjoy my job and I get along with most people there," said Carlo Pedone, a Boston screener. Said Carl Maccario, another Boston screener, "It's a brand-new organization that sprang up overnight, and it's going to have growing pains." A screener at Houston's George Bush Intercontinental Airport said: "Most of the people who complain are slackers. I give it all. I just keep right on going. There's some people there where nothing goes right for them. Most of them don't do a good job."

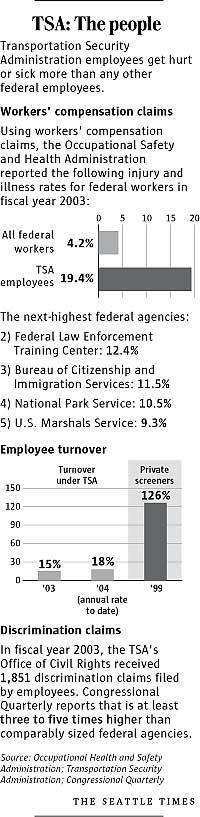

Sometimes the animosity has become downright ugly. In Seattle, workers wrote "slut" on one manager's picture and drew horns and a Star of David on a Jewish supervisor's photograph. Across the country, many screeners have reached out to unions, members of Congress and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Although TSA forbids screeners to bargain collectively, about 700 employees have joined the American Federation of Government Employees, seeking help with lawsuits, discrimination complaints and better working conditions. "There is no effective safety valve at TSA," said Peter Winch, a national organizer for the union. "There is no good way to raise concerns about the way you're being treated." Hatfield, the TSA spokesman, said the agency is addressing that. Its civil-rights office, which received about 1,850 discrimination claims last year, has expanded from two to 26 employees. TSA's ombudsman's office has grown from 22 to 49 employees. Last year, Hatfield said, 7,000 employees contacted the office with questions or complaints. Training falls short For decades, government reports have blamed insufficient training for airport screeners missing weapons. When they worked for private security agencies hired by airlines, screeners received minimal instruction. A 1987 government audit described training sessions where screeners simply watched a videotape without anyone there to answer questions. Screeners also weren't tested on what they had learned. TSA's training program is designed to be more demanding, but in some ways doesn't achieve its promise. TSA requires, for example, that screeners get three hours of refresher training a week, emphasizing such screening techniques as interpreting X-ray images. But some screeners in Houston say their training consists mostly of a supervisor reading from a document, with little give and take. And security directors at the nation's five largest airports have told congressional investigators that they don't comply. Diverting so many screeners to training would leave checkpoints understaffed, the directors said. Instead of three hours a week, their screeners get about three hours of training a month. A former screening supervisor in one Midwestern city told The Times that managers directed her to submit false training reports. She complained at first, but then went along, she said. Her reports said screeners had met the three-hour requirement, when in fact they had not because of competing demands. "Yes, I did do it — I'm not proud of it but I did," she said. In Seattle, a building devoted to training — rented by the TSA for $7,500 a month — lacks phone lines, making it difficult to access online training, TSA employees said. Government inspectors also have faulted the TSA for providing insufficient training to supervisors and for lax certification requirements. The TSA hired contractors to help train and certify about 30,000 baggage screeners on the use of explosives-detection equipment. But a government audit denounced the certification process. Instructors used practice questions identical to those on the final exam. And some questions offered little challenge anyway. One asked what a detonator does. It detonates, the correct answer said. Another asked what an explosives-detection system detects. Explosive devices, the correct answer said. That test, Hatfield said, has since been overhauled. To keep their jobs, federal screeners must pass annual recertification tests. But that process has come under fire, too. In her February memo to Stone, Florian described how TSA keeps changing the procedures screeners must follow — even doing so during the recertification process. Screeners who flunk receive only 30 minutes of remedial training and are retested within 24 hours. "We are not aware of any other non-probationary federal employee that is subjected to this type of treatment," Florian wrote. In Seattle, managers were asked by TSA headquarters to speed up the termination process for employees who failed the recertification test. But in e-mails, Seattle managers reminded headquarters that screeners had a right to appeal. The managers also said some screeners had received less than the allotted half-hour of remedial training. Injuries, long hours TSA employees get hurt or sick more than any other federal employees, suffering back, shoulder and knee injuries, pulled muscles, tendinitis, and cuts and puncture wounds from sharp objects tucked in luggage.

Overall, 4.2 percent of federal workers suffered work-related injuries or illness. TSA's percentage was 19.4 — nearly five times as high, topping Park Service employees and federal marshals. Even worse numbers loom. This fiscal year, one in four TSA workers will get sick or injured, according to an OSHA projection using first-quarter statistics. Those numbers also create a cycle: the more workers out sick or hurt, the greater the strain on those who remain, causing fatigue and more injuries. Without question, more physical labor is demanded of the typical TSA employee than, say, a financial analyst for the Office of Management and Budget. In fact, Hatfield said, TSA's injury rate isn't much higher than United Parcel Service's. But many screeners attribute TSA's injury rate to insufficient training and inadequate safety equipment. They want, for example, more training on lifting heavy objects, and gloves that resist punctures. Screeners say they regularly lift bags weighing 70 pounds or more. TSA tells screeners to get help with bags heavier than 40 pounds and warns that not doing so could jeopardize workers' compensation claims. But because of staffing shortages, screeners say, help is hard to come by. In Los Angeles, screener Obed Quintero said he hurt his back lifting heavy bags and went on workers' compensation for seven months. When his compensation stopped, Quintero said, he asked for light duty. But the TSA couldn't find him a position, Quintero said, and let him go. "I did an excellent job," he said. "It's kind of a shame, because what we were doing was very important." Too often, screeners say, their claims for workers' compensation meet with delay or denial. Jonathan David, a Portland, Ore., screener who injured his back, said he was nearly evicted from his apartment as he waited for his claim to be approved. Some screeners say such frustrations even dissuaded them from pursuing compensation — suggesting the agency's injury rate may be higher than reported. Sometimes, long hours compound the stress. Screeners can go weeks without a day off. In Boston, some have worked so many double shifts "they are ready to drop," says Michael Jasilewicz, a former screener. Breaks can be six hours apart. After two hungry and tired screeners were denied breaks, they actually passed out, Jasilewicz said. In Los Angeles, a screener who works 10-hour shifts said the last two hours are the hardest. "I keep saying, 'I can do this, I can do this,' " she says. When working the X-ray machines, she sometimes has to catch herself. "If I feel like I'm falling asleep and dozing off, I'll look up to see if anybody can relieve me. And nobody's out there. Everybody is doing two to three things at a time. And I don't want to interrupt anybody, because they're busy." TSA officials acknowledge that they rely heavily on overtime, especially during the busy summer months. In 2003, TSA employees worked more than 7 million hours of overtime — an average of three weeks per employee. Overtime has declined this year, but some screeners at busier airports say they still pull long hours, sometimes clocking 20 hours of overtime in a week. For screeners, mandatory overtime and rigid scheduling create stress, dashing planned vacations or requiring personal affairs to be rearranged on a moment's notice. In Seattle, a screener ordered to work overtime reluctantly left her children, ages 12 and under, at home for three hours, unsupervised. She said her supervisors told her: Work, or lose your job. One Boston screener was to be best man at his nephew's January 2003 wedding in Florida. In October, he requested the time, only to have supervisors say he was asking too early. So he asked again in November, only to be told in late December — mere days before the wedding — that his request was denied. Ordered to work, he quit. He went to the wedding. More than a year later, TSA sent him a letter. Because of a payroll error, it said, he owed TSA about $1,000. Employee "ghosts" Work conditions that include forced overtime, a high injury rate and flagging morale typically lead to high turnover. And at TSA, examples abound of workers calling it quits. When a Seattle screener resigned in December, she wrote: "The stress of this job is far too much for me to endure." Nonetheless, TSA's turnover is a vast improvement over that of the private work force that preceded the agency. In 1987, screener turnover at some airports was about 100 percent a year — churn so great that the entire work force was, in effect, replaced. By 1999, turnover had reached 126 percent. Screeners would bolt for other jobs just as they mastered such tasks as detecting weapons in X-ray images. TSA, by comparison, reported turnover of 15 percent last year. So far this year, Hatfield said, it's running at a rate of 18 percent. But TSA's turnover may be higher than reported, because of the agency's struggle to track its workers. In fiscal year 2003, the government reported that 131 of TSA's Seattle employees left. But internal pay records, obtained by The Times, show the actual number was at least 193 — a substantial difference that would drive turnover up. TSA employees in Seattle told The Times that the airport has had multiple staffing lists with inconsistent employee counts. Instead of tracking each screener's hours electronically — an early goal of the agency — TSA records pay manually, then sends the information to personnel contractors that have been widely criticized for losing or mishandling paperwork. In some cases, TSA has ended up with what one internal document calls "ghosts" — hires who didn't show up for work but are still listed as employees. In Seattle, screener Tenya Manny quit Jan. 6. TSA stopped paying her, but for five months it still listed her as an employee — a mix-up that kept her from collecting nearly $2,000 in outstanding compensation. Manny said it took the intervention of a congressman's staff to clean up the mess. "It happens," she said, "when you have a collection of people that couldn't fight their way out of a box with instructions." Ken Armstrong: 206-464-3730 or karmstrong@seattletimes.com Cheryl Phillips: 206-464-2411 or cphillips@seattletimes.com Steve Miletich: 206-464-3302 or smiletich@seattletimes.com

Seattle Times staff reporters Christine Willmsen and Alyson Beery and news researchers Miyoko Wolf and Gene Balk contributed to this report.

Copyright © 2004 The Seattle Times Company

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

seattletimes.com home

Home delivery

| Contact us

| Search archive

| Site map

| Low-graphic

NWclassifieds

| NWsource

| Advertising info

| The Seattle Times Company