Originally published September 20, 2014 at 7:38 PM | Page modified September 22, 2014 at 3:44 PM

Oso-area residents grapple with life six months after slide

Six months after the Snohomish County landslide, the communities are preparing for a long-term emotional recovery that many are just now starting to think about. On Saturday, survivors and families of landslide victims will plant a tree for each of the 43 people who died March 22.

Seattle Times staff reporter

MARCUS YAM / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Dave Schonhard, solid-waste operations manager of Snohomish County Public Works, prepares Aug. 22 to brief members of the Highway 530 Landslide Commission at their first visit to the site of the deadly landslide near Oso.

LINDSEY WASSON / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Dayn Brunner, brother of landslide victim Summer Raffo, hopes to see a small memorial area built along the road.

LINDSEY WASSON / THE SEATTLE TIMES

A string of cars heads east toward Darrington last Thursday, led by a pilot car and followed by a security vehicle, on the new Highway 530 near Oso. With debris cleanup finished, crews are working to completely open the road by Tuesday.

Darrington Mayor Dan Rankin

Memorial service

What: The Washington State Department of Transportation will help survivors and families of landslide victims plant a tree for each of the 43 people who died March 22, in a small grove just east of where Steelhead Drive used to be. Community members will then be invited to see the trees and walk along the new stretch of highway with first responders.

When: 9:30 a.m. Saturday, Sept. 27

Where: Buses and shuttles will take people to the event site from the Oso Fire Department and Darrington Rodeo grounds.

Oso landslide: Comprehensive coverage of the March 22 disaster and recovery

The Seattle Times

A collection of stories and visuals about the disaster, why it may have happened and the people it affected.

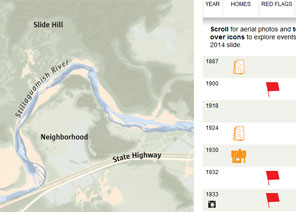

Interactive: Building toward disaster

THE SEATTLE TIMES

Use an interactive to see how, even as warnings mounted, homes kept being built in slide-prone Steelhead Haven.

Remembering the victims

Compiled by The Seattle Times

Read about the lives of the victims.

Interactive map: A detailed view of the neighborhood hit by the landslide

Garland Potts, Cheryl Phillips / The Seattle Times

Use an interactive tool to see the landslide’s deadly path.

TIMES WATCHDOG

![]()

DARRINGTON — Digging, searching and rebuilding have filled most of the last six months for hundreds of Darrington and Arlington residents living on either side of the Highway 530 landslide that killed 43 people on March 22.

Now much of that work has slowed. The summer tourism season that draws people to local music festivals, hiking and river rafting is winding down. Cleanup of the slide area was officially considered finished earlier this month. This Tuesday, the rebuilt stretch of Highway 530 is expected to open. Victims will be memorialized Saturday near the highway with the planting of 43 trees.

As quieter, wetter seasons approach, the communities are preparing for a long-term emotional recovery that many are just beginning to think about.

“We are just beyond the survival-mode part — this is new territory for us,” said the Rev. Tim Sauer, chairman of the area’s long-term recovery group. “We’re just beginning to brainstorm our strategy for this, so I don’t know what it will look like yet.”

Sauer, pastor of Immaculate Conception Parish in Arlington, says counselors, case managers and grief support groups have been available for months. But they haven’t been used as much as he’d hoped yet, despite door-knocking and announcements posted in high-traffic areas.

Renee White remembers when her city of Joplin hit the same point about six months after a tornado ripped through the small Missouri city in 2011, killing 158 people. She was in charge of the area’s long-term mental and emotional recovery strategy and found that when friends and family were eventually able to get more people to open up — six to nine months after the disaster — the community became more ready to rebound and look to the future.

“I think as Americans, we’ve been so instructed to pull ourselves up by our bootstraps and keep our private problems bottled up that we don’t seek help when we need to,” White said. “You have to come to a point where you don’t dwell on it, but accept it as a chapter in your life that cannot be erased, and acknowledge what you can gain from it.

“Some people come out stronger from it than they’ve ever been.”

Pulling together

In the months since Dayn Brunner found his 36-year-old sister, Summer Raffo, in the muck, members of his large, close family have found themselves in various stages of healing. He, his two teenage sons and many of his 11 other siblings were among the first on the scene of the slide that swallowed Raffo’s blue pickup as she headed to a horseshoeing appointment.

There are times when Brunner’s three children are more receptive to school counselor sessions than others, and times when he’s noticed himself becoming angry faster than he used to. His once-outgoing mother, who lived next door to her daughter, has hardly been able to step outside her Darrington home.

“She still looks outside the window every day to see if Summer’s car is pulled up in the driveway,” Brunner said.

With the exception of counseling at school for his children, he is not aware of anyone else in his family seeking counseling. He knows some of them should, but it’s not something Brunner wants to push.

“No one’s going to force you to talk about what you’re feeling, but if you want to talk, I’m here,” is something Brunner says he’s telling his loved ones often these days.

Sauer says paid workers from Catholic Community Services often check in on people. But White said that in Joplin, no one was better than family and friends at getting people to use more counseling resources.

Feeling safe at home

A key part of the area’s emotional and economic recovery — especially Darrington’s — also depends on residents feeling safe at home again.

It would seem the worst has happened, but events preceding and following the slide have produced fears about the quality of local emergency-response strategies and about how transparent county officials are being about potential dangers nearby.

At the first and likely only Highway 530 Landslide Commission meeting to be held in Darrington, Shari Brewer wondered last week how quickly the area would receive help in the future should an earthquake or flood take out a local bridge. She said that in the first few hours after the slide, her daughter and son-in-law were among a small number of volunteer firefighters available to respond on the Darrington side.

A heavy skepticism of Snohomish County officials bled through Jaimie Mason’s tearful request to the commission to make sure studies and reports indicating environmental dangers are publicized and acted upon. The commission has until December to hand Gov. Jay Inslee a report summarizing suggestions for how disaster response could be improved.

Mason, who was one of many civilians who searched through the debris, said that working through her memories of the landslide aftermath is a slow process.

“I can speak for hours about what worked and what didn’t work out there, what we can do better — I’ll write that down,” said Mason. “But it’s been slow going and it’s not something I can do very long before I need to stop because, emotionally, there’s only so much I can deal with in a day.

“I’ve got work and I’ve got a 6-year-old who misses his classmate.”

For Darrington residents who will have to regularly drive straight through the slide zone on a rebuilt Highway 530, there are mixed feelings.

Brunner, who works for the Tulalip Police Department, knows it’s never going to be an easy drive again.

“It’s sacred ground. Everyone gets quiet when you drive across it. No one jokes,” Brunner said. “You remember everyone who lived there, the nice houses, the people who would wave at you when you honked, the gardener who grew and gave away squash and zucchini, the man who’d always be chopping wood.”

Brunner said he hopes someday the area is completely sectioned off, that a blanket of colorful plants returns, and that a small memorial park is created nearby. Even in its mostly cleaned-up state, mounds of dirt and debris still dot the grayish-brown landscape.

“Right now it’s still all one color, and reminds me of when we first saw the slide,” Brunner said. “It was so eerie. We heard moans, and we were all alone.”

Darrington Mayor Dan Rankin is relieved that the highway, an economic lifeline for his town, will open soon. For months, pilot cars have led traffic down one-way routes on or near the rebuilt highway, and signs on Interstate 5 have suggested detours around it.

As Rankin helps the community settle in to a new normal, he’s still working from morning to night to line up grants and investments that will help survivors, local business owners, and future development in the area. In the last six months, Rankin has spent only one day at the sawmill he owns and worked at full time before the slide.

“There’s a zillion and one things to focus on,” Rankin said as a steady stream of texts and phone calls came in to both his desk and cellphone. He has so many meetings with local, state and federal officials that he said he feels guilty about not being able to personally check in on people in town as often as he used to.

At the same time, he’s excited about some of the biggest redevelopment projects he hopes to bring to the area through new grants and investments. They’re projects that would have been welcome even before the slide, when the recession and declining logging industry had already heavily damaged the logging town’s economy.

Among them is a proposal to build an environmentally-focused STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math) education facility for youth that would help prepare them for jobs while learning more about where they live. Those youths could then teach what they know to other schools that visit on field trips.

Rankin is also involved in trying to secure an Economic Development Administration grant to help redevelop the entire Stillaguamish Valley between Arlington and Darrington.

“There’s going to be a lot of work between now and April to explore what the possibilities in the Stillaguamish Valley are,” he said.

Alexa Vaughn: 206-464-2515 or avaughn@seattletimes.com. On Twitter @AlexaVaughn.

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!