Originally published April 23, 2014 at 8:53 PM | Page modified April 24, 2014 at 8:44 AM

Log wall at base of mudslide hill required repeated repairs

A log barrier built at the base of the Snohomish County hill where a mudslide occurred last month needed repeated repairs. It was designed to protect fish and stabilize the slope.

Seattle Times staff reporters

Oso landslide: Comprehensive coverage of the March 22 disaster and recovery

The Seattle Times

A collection of stories and visuals about the disaster, why it may have happened and the people it affected.

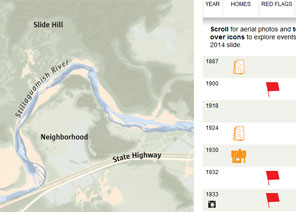

Interactive: Building toward disaster

THE SEATTLE TIMES

Use an interactive to see how, even as warnings mounted, homes kept being built in slide-prone Steelhead Haven.

Remembering the victims

Compiled by The Seattle Times

Read about the lives of the victims.

Interactive map: A detailed view of the neighborhood hit by the landslide

Garland Potts, Cheryl Phillips / The Seattle Times

Use an interactive tool to see the landslide’s deadly path.

TIMES WATCHDOG

![]()

In 2006, after a major mudslide caused flooding and triggered concerns of more slides to come, the state of Washington funded separate projects to shore up two unstable hills that rose from the North Fork of the Stillaguamish River in Snohomish County.

One project targeted Skaglund Hill, just south of the Stillaguamish, with Highway 530 near the bottom. The state Department of Transportation spent $13.3 million and built a rock wall, to protect drivers passing through. This defense was referred to as “hard armor.”

The other project targeted the Hazel slope, just north of the Stillaguamish, a hill with such a long history of slides that it dumped more than a million cubic yards of fine sediment into the river. Traditionally, rock was used to protect banks, according to state records. But in this instance the state wanted to mimic nature, to protect fish passing through. So the state spent $1 million on a wood barrier, a defense referred to as “soft armor.”

The wood barrier, called a crib wall, was 15 feet high and 1,500 feet long. By keeping the river from eroding the hill’s base, it was also intended to reduce the risks of a massive slide. But last month the Hazel slope collapsed, producing a devastating mudslide that killed more than 40 people across the river.

The natural catastrophe has geologists evaluating various factors that might have contributed to the slide, from heavy rains in the weeks before, to logging on the plateau above the hill, to erosion of the hill’s base, or toe.

The slide also has generated scrutiny of the county’s decision not to buy up homes across the river, to protect residents by moving them out. The county endorsed the idea of a crib wall, with its twin goals of stabilizing the hill and enhancing the environment.

Almost from the get-go, the crib wall required repairs as it confronted the force of the river, according to documents obtained by The Seattle Times. At the base of the hill — called Slide Hill by some residents familiar with its past — the crib wall became part of a decades-long struggle of man versus nature, with man unable to keep the slope from falling away.

Restoring nature

Sediment from the Hazel slope reaches 35 miles downstream, going past Arlington to the estuary at Port Susan, according to state documents. That stretch of the river is home to chinook, coho, pink and chum salmon, and steelhead, cutthroat and bull trout.

For decades, the watershed’s fish stock has been depleted by what comes off the surrounding hills and by what man has done to the river.

The North Fork was once a complex flood plain with lots of wood in the channel to provide deep, cold pools that fish used for rearing and to escape predators. But around the turn of the 20th century, the federal government removed trees and jams from the waterway to help with navigation; wood was also cleared by pioneers heading upstream to log, mine and homestead.

To restore the river’s complexity — and to rehabilitate the habitat for fish — the Stillaguamish Tribe received funding in the 1990s to build engineered log jams along the North Fork. But the problem of sediment, particularly from the Hazel slope, remained. The sediment harmed spawning beds, its volume too much for the river to flush.

In the 1950s, state officials mulled ways to keep the Hazel slope’s sediment from clouding the river. One plan would have guided the river away from the hill with long revetments built of rock from nearby quarries.

Instead of pursuing that option, state officials chose in 1960 to build a 1,000-foot berm made of material from the river bank. That wall didn’t even survive the following winter, as high water destroyed much of it.

Officials returned to the rock-revetment idea in 1962, building a wall along the same path as the earlier berm. While the new revetment provided more strength, clay flowing from the hill went over a portion of it in 1964. Then, in 1967, a larger mudslide buried the whole thing. In the end, officials had spent $73,000 with little to show for it.

Trouble from the start

In 2006, the Stillaguamish Tribe set out to build the crib wall using money from the state’s Salmon Recovery Funding Board and a grant administered by the state Department of Ecology. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers issued a permit for the project, which was intended to stimulate chinook-salmon and bull-trout runs, and to isolate the river from the slide, thereby reducing “the likelihood of catastrophic failure,” according to federal documents.

Construction began in July of that year and was completed later that summer. The wall was built with logs — from 2 to 3 feet in diameter — lashed together with wire cable and anchored with buried, concrete blocks weighing 5,500 pounds. Woody debris was also added, to slow the current and create pools for fish.

But documents filed with the state by representatives of the Stillaguamish Tribe have detailed how the wall has continually suffered damage from a variety of forces, triggering one repair after another.

First, in the area where the river hit the crib wall with the most force, a portion sank eight to 10 feet and a spring developed that liquefied the material just behind the barrier, documents say.

In 2009, the tribe made repairs that included diverting the spring and using new anchors to reinforce the wall.

Next, neighborhood kids shot off bottle rockets that accidentally burned the woody debris in the section that had just been fixed.

“Repairs were made with cable and hand tools the best we could, but the crib-wall section subjected to the greatest hydraulic forces was still significantly weaker than the rest of the crib wall,” according to a document filed by the tribe.

Then, the North Fork flooded, its flows the highest in 85 years of record-keeping. “These flows were too much for the tortured section of the crib wall,” the document said. A cable holding the logs together snapped, and a section of the wall about 70 feet in length was torn out.

In 2011, the tribe undertook its most elaborate repair to this section of the wall. To keep from stirring up dirt and debris, a repair raft was constructed on the south side of the river, then floated across and inserted into the missing part of the wall.

Pat Stevenson, the environmental manager for the Stillaguamish Tribe, said he wouldn’t have done anything different with the wall and doesn’t think anything could have stopped the mudslide from happening.

The goal was to make the crib wall as fish friendly as possible, he said. And the plan worked. A year after the wall was built, the tribe saw Chinook spawning downstream and eventually saw them gathering around the crib wall.

“That was pretty significant,” Stevenson said.

After the missing section was replaced in 2011, no other repairs were needed, Stevenson said. He visited the river’s edge the Thursday before the mudslide occurred; the crib wall looked no different from it did three years before.

Ken Armstrong: karmstrong@seattletimes.com or 206-464-3730; Mike Baker: mbaker@seattletimes.com or 206-464-2729

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!