Originally published April 22, 2014 at 8:03 PM | Page modified April 23, 2014 at 6:15 AM

Snohomish County to weigh development moratorium in landslide areas

A month after the deadly Oso mudslide, the Snohomish County Council will consider an emergency moratorium on development in areas at risk of landslides.

Seattle Times political reporter

Oso landslide: Comprehensive coverage of the March 22 disaster and recovery

The Seattle Times

A collection of stories and visuals about the disaster, why it may have happened and the people it affected.

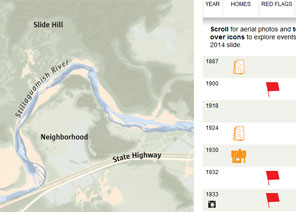

Interactive: Building toward disaster

THE SEATTLE TIMES

Use an interactive to see how, even as warnings mounted, homes kept being built in slide-prone Steelhead Haven.

Remembering the victims

Compiled by The Seattle Times

Read about the lives of the victims.

Interactive map: A detailed view of the neighborhood hit by the landslide

Garland Potts, Cheryl Phillips / The Seattle Times

Use an interactive tool to see the landslide’s deadly path.

TIMES WATCHDOG

![]()

The Snohomish County Council will consider an emergency moratorium on development in areas at risk of landslides.

Dave Somers, president of the council, said he’ll propose a vote on the six-month ban at a council meeting Wednesday.

Somers, who was in Arlington Tuesday during President Obama’s visit to the site of the March 22 mudslide, said the moratorium would apply to new construction throughout the county within a half-mile of landslide hazard areas mapped by the county.

The ban would not halt projects that have already received building permits, Somers said. The moratorium would give the county time to do a more detailed assessment of landslide risks and develop new policies if needed, he said.

U.S. Rep. Rick Larsen, D-Everett, said he supported the move.

“Step one is the county should put a halt to building there” in landslide areas, Larsen said. Then the county should step back, update its maps of slide-prone areas, and review whether its development regulations and warnings for homeowners in such areas can be strengthened.

Somers said that before the Oso disaster, the county had been in the midst of updating its rules on building in environmentally sensitive areas. But he said the focus had been more on flood plains and agricultural land, not landslides.

“Frankly, this issue wasn’t on the radar screen,” Somers said. “We have to re-look at that.”

The hillside that gave way and destroyed the Steelhead Drive community near Oso had experienced numerous slides over the years. But geologists were surprised by the size and speed of the slide.

The county had considered buying up and emptying property later wiped out in the mudslide but decided instead to stabilize the base of the slope and leave residents where they were.

While it’s fairly easy to identify landslide-prone slopes, it’s much harder to predict how far slides will travel, University of Washington geomorphologist David Montgomery told The Seattle Times earlier this month.

Geologists who analyzed slide risks along the North Fork of the Stillaguamish River warned in 1999 that a “large catastrophic failure” was possible. But in the worst-case scenario they deemed most likely, the runout was estimated at less than a quarter of a mile. The Oso slide ran out for nearly a mile.

“Any geologist who went out there would say, yes, this situation is ripe for a landslide,” said Richard Iverson, a landslide expert from the U.S. Geological Survey’s Cascades Volcano Observatory. “But in my mind, the story isn’t that a landslide occurred, but the type of landslide that occurred.”

He blames the disaster on a combination of unusually wet weather, erosion at the toe of the slide and local geology.

Jim Brunner: 206-515-5628 or jbrunner@seattletimes.com. On Twitter @Jim_Brunner

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!