Originally published April 19, 2014 at 5:03 PM | Page modified April 20, 2014 at 12:11 AM

Mudslide donations showcase power of crowdfunding

In the wake of the Oso mudslide, dozens of crowdfunding pages have been set up online to help survivors financially as they move on with their lives. The sites are an easy, personal way to help, but using them is not without risk.

Seattle Times staff reporter

Oso landslide: Comprehensive coverage of the March 22 disaster and recovery

The Seattle Times

A collection of stories and visuals about the disaster, why it may have happened and the people it affected.

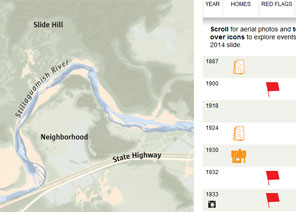

Interactive: Building toward disaster

THE SEATTLE TIMES

Use an interactive to see how, even as warnings mounted, homes kept being built in slide-prone Steelhead Haven.

Remembering the victims

Compiled by The Seattle Times

Read about the lives of the victims.

Interactive map: A detailed view of the neighborhood hit by the landslide

Garland Potts, Cheryl Phillips / The Seattle Times

Use an interactive tool to see the landslide’s deadly path.

TIMES WATCHDOG

![]()

The Monday after the devastating mudslide that killed Seth Jefferds’ wife and his step-granddaughter, Dan Welty hastily set up a GoFundMe account where donors could contribute money to help Jefferds.

Welty started with a goal of $10,000 to assist his friend, a volunteer firefighter. “The guy had lost every single thing he had,” Welty said, including his wife, Christina, 45, and 4-month-old Sanoah Huestis.

By the time Welty woke up Tuesday, $1,000 had been donated. By the end of the day, the account was up to $10,000. Then it grew to $20,000. Then $30,000.

Three weeks later, 589 donors have generated $54,000 on the “Seth Jefferds Mudslide Recovery Fund” page.

“I thought, ‘you’ve got to be kidding me,’ ” Welty said. “I was in tears half the time. It was amazing.”

In the aftermath of the March 22 mudslide that killed at least 39 people and destroyed a neighborhood, residents in the Puget Sound area and beyond looked for ways to help. Rather than going through traditional charities such as United Way and the American Red Cross, which have collectively raised well over $4 million for mudslide relief, some donors turned to websites like GoFundMe, YouCaring and CrowdRise as a way to contribute directly to a specific person or cause.

Four weeks after the mudslide, more than $320,000 has been raised through 3,470 separate donations on more than 30 pages. Some are dedicated to traditional relief funds, like the Red Cross, while others, like Welty’s page, go toward helping a specific person.

Crowdfunding pages are a way to put relief efforts into donors’ own hands, creators say. People all over the world can make contributions with a single click.

Unlike with larger, established charities, where the donor generally gets no more than a receipt, people who give to crowdfunding pages can see personal photos of the beneficiaries and read updates on their progress.

They also can leave messages and publicly show how much was donated, or they can remain anonymous.

But along with the ease and personal nature of the Web pages comes concern about whether all the funds are legitimate and whether it’s fair that one family’s crowdfunding page may raise $50,000 while another’s stagnates in the hundreds of dollars.

No guarantees

While larger charities like the Red Cross have long histories and well-established credibility, successful crowdfunding pages must convey authenticity through other means.

On their websites, crowdfunding platforms acknowledge there is no guarantee the money given will go to the intended recipients, and donors should either contribute to people or groups they know, or exercise caution when giving to people they don’t know.

State Attorney General Bob Ferguson and Secretary of State Kim Wyman issued a consumer alert a few days after the mudslide urging donors to be aware of potential charity scams by never giving credit-card information over the phone, being wary of “new” charities with unverifiable background information and avoiding cash donations.

As of Friday, the Secretary of State’s Office hadn’t received any complaints about crowdfunding sites, though the office warns there is no agency tracking all the sites and where the money is going.

“I don’t want to say they are always bad or they are always good, but there is no way to verify if they are legitimate,” Corporations and Charities Division Director Pam Floyd said. “If that person is raising money and says he or she is doing whatever with it, you are taking them at their word.”

But GoFundMe CEO Brad Damphousse said in an email that the majority of activity on the GoFundME website occurs between family and friends, “so the level of trust and oversight is high.” Pages can link to the creator’s Facebook page so donors can get more information about the creator.

“The earliest donors are essentially vouching for a campaign’s authenticity,” Damphousse said. “Once this ‘social proof’ is established, it’s usually a good indicator that it’s safe for others to donate as well.”

The “social proof” is why Welty decided to create a fund, he said.

“With a communitywide donation, I don’t know if it’s going to the right places, but I know it probably will because there are so many caring people,” he said. “But with this, there isn’t even a tiny shadow of a doubt it’s going to the right person.”

Crowdfunding has cost

The premise of each crowdfunding site is similar: A user creates a Web page for a person or organization, sets a goal amount and provides a time frame that the page will be available. Donors find the page, enter a donation amount and provide payment information. The donations are then transferred directly into a specific bank or PayPal account where they can be withdrawn by the page creator or beneficiary.

Crowdfunding sites are not free. They usually take 3 to 10 percent of the money donated or are financed through user contributions. If the donations are given to a specific person, the sites warn, the money likely isn’t tax-deductible, but it may be if the money is donated to a crowdfunding page for a charitable organization.

Welty’s page started with donations from Jefferds’ friends and family in Washington. There were also a lot of donations from Minnesota, where Jefferds’ family lives.

As the page has grown, donations have come from multiple states and as far away as Australia.

Some pages for people who survived the mudslide address the immediate needs of those affected in ways traditional charities could not. A page for Mark Lambert on GoFundMe has generated $22,500 from 161 people. Lambert was injured in the mudslide and remains at Harborview Medical Center. He could be facing a hefty bill for his care. The average expense incurred in Washington hospitals for inpatient care is $2,875 a day, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Lorinda Hays, an Arlington horse trainer, started the GoFundMe page “Help Horses of the Arlington Mudslide” to provide supplies for horses and their owners who had to evacuate their ranches. The page has raised $970.

“I am continually impressed by the outpouring of generosity that is represented by our local horse community, as well as complete strangers from around the country,” Hays said.

Not a competition

Charities shouldn’t see crowdfunding pages as competition, said Nora Ganim Barnes, director of the Center for Marketing Research at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. The center has done extensive research on the impact of social media and charities.

“The missions are different, in terms of long-term strategy and goals,” Ganim Barnes said.

Colin Downey, American Red Cross communications director for the Western Washington region, agrees. The national charity has used CrowdRise, another crowdfunding site, as a way to raise funds. Donors have contributed $4 million on its page for relief efforts across the country.

“We understand that we are one way that people can provide help in these situations, and it takes a community to provide assistance in these disasters,” Downey said. “We always encourage the generosity of the public to go wherever they feel is best directed.”

Social media are key

The amount of money raised through crowdfunding for specific mudslide victims or causes varies greatly. Some pages have raised tens of thousands of dollars, while others haven’t passed $100.

The amount can depend on multiple factors: how prominent a person or cause has been in the media, the number of donors, or how much the page has been circulated through email and social media. On Fundly.com, 25 percent of the donations come from social-media sources, the crowdfunding site says.

A GoFundMe page set up for the family of Denver Harris, 14, who was killed in the mudslide, has generated nearly $18,000 and has been shared on Facebook more than 1,100 times.

In contrast, another GoFundMe page set up “to aid mudslide victims and volunteers” has generated $160 and has 15 Facebook shares.

Social media is the “lifeblood of those funds,” Ganim Barnes said.

“They simply don’t have the audience or platform of the larger charities,” she said. “The name of the game is awareness. People can’t donate to something they don’t know anything about.”

After the mudslide, some pages were created to help surviving family members with travel or funeral expenses, such as the page “Hope for Jovan Mangual,” set up on YouCaring.com. Nicole Ponce, a neighbor of 13-year-old Jovan Mangual’s father, Jose Mangual, set the page up the day after the mudslide to help with Mangual’s travel costs from Colorado to Washington so he could assist the search for victims.

Jovan; his stepfather, Billy Spillers; and half-sisters Kaylee Spillers, 5, and Brooke Spillers, 2, died in the mudslide. A YouCaring fund for Jovan’s mother, Jonielle Spillers, who wasn’t home at the time of the slide, has generated $50,000.

Now, the $7,000 raised so far on Jose Mangual’s page — with funds transferred to Mangual’s account every night — will go toward helping him set up a memorial service for his son in Puerto Rico, where his family lives, Ponce said.

Finding “new normal”

Stanton Bonnell started a page to help friends Larry Gullikson and Bob Aylesworth, who lived next door to each other on Highway 530. Gullikson’s wife, Bonnie Gullikson, died in the mudslide, and both families’ houses were destroyed. The page has raised $28,000 from 72 separate donations.

“I realized how easy and quick it is for people to donate this way,” Bonnell said. “You can put it on Facebook; email the pages out to everybody. It was an easier and faster way to raise money and help them out.”

Other pages focus on rebuilding, like “Relief Fund for Ron and Gail Thompson,” which has brought in $39,700 from 364 donations. The Thompsons were at Costco when the mudslide hit, but their house on Steelhead Drive, which they purchased in 2003 for $214,000, was destroyed, said their daughter, Jennifer Thompson-Johnson, who set up the page with a friend’s assistance. Their insurance doesn’t cover natural disasters, so Thompson-Johnson started the fund to help them as they work to “find our new normal.”

“Everything they had was invested in that property, and the only thing they owed on was the John Deere tractor,” Thompson-Johnson said. “They want to buy something in Oso, but we don’t want them to rush into anything. They’re in their 60s. They can’t afford a 30-year mortgage.”

The fund for Seth Jefferds will help Jefferds and his stepdaughter, Natasha Huestis, move on with their lives, Welty said. For now, he’s still in awe of the response the page received.

“That is what really gets me,” Welty said. “I started this on Facebook, and I only have 120 friends on Facebook. It just grew by leaps and bounds.”

Paige Cornwell: 206-464-2530 or pcornwell@seattletimes.com

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!