Originally published April 14, 2014 at 8:58 PM | Page modified April 14, 2014 at 9:04 PM

State lands chief breaks vow, takes timber-industry money

TIMES WATCHDOG: During his successful 2008 campaign to become state lands commissioner, Peter Goldmark pledged not to accept timber money. But he has collected about $100,000 from those companies, and environmental supporters are concerned he is growing too close to the logging industry.

Seattle Times staff reporters

Oso landslide: Comprehensive coverage of the March 22 disaster and recovery

The Seattle Times

A collection of stories and visuals about the disaster, why it may have happened and the people it affected.

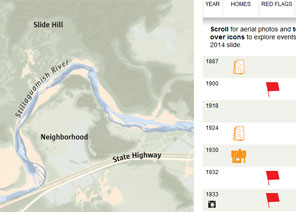

Interactive: Building toward disaster

THE SEATTLE TIMES

Use an interactive to see how, even as warnings mounted, homes kept being built in slide-prone Steelhead Haven.

Remembering the victims

Compiled by The Seattle Times

Read about the lives of the victims.

Interactive map: A detailed view of the neighborhood hit by the landslide

Garland Potts, Cheryl Phillips / The Seattle Times

Use an interactive tool to see the landslide’s deadly path.

TIMES WATCHDOG

![]()

As he campaigned in 2008 to become Washington state’s top logging regulator, Peter Goldmark attacked his opponent for a “reprehensible” conflict of interest — accepting money from timber harvesters while allowing them to conduct clear-cuts in landslide-prone areas.

Goldmark pledged that he was the candidate to do away with backroom deals and restore trust to the office.

“I will not accept money from the industries that I’ll be regulating,” the Democrat said at a public forum in Gig Harbor that year, during his successful campaign to unseat Republican Doug Sutherland, the incumbent commissioner of public lands.

His vow didn’t last.

Over the past three years, Goldmark has accepted about $100,000 in campaign contributions from timber and wood-product companies — 20 percent of the money he’s collected over that time, according to a Seattle Times analysis.

For example, Weyerhaeuser, which Goldmark cast as a villain during his 2008 campaign, is among the donors.

Goldmark said he didn’t sustain the pledge because he’s not influenced by the money.

Some key environmental leaders who helped foment and fund his campaign now say they’re frustrated that he has grown too close to timber companies. They are particularly concerned that the Department of Natural Resources (DNR) hasn’t done more to restrict logging in landslide-prone areas.

The divide between Goldmark, who was re-elected as lands commissioner in 2012, and some environmentalists has widened after last month’s deadly mudslide in Snohomish County.

Goldmark, in an interview last week with The Seattle Times, said he will not speculate on what might have caused the mudslide until scientists complete a review. Some outside geologists have said the impact of a 2004 clear-cut on the terrain above the slide could not be ruled out.

However, shortly after the mudslide, Goldmark downplayed the role of that clear-cut, which occurred about four years before he took office. He noted that the timber harvest was relatively small in size and accused anti-logging advocates of trying to seize on people’s emotions after the tragedy.

“Slides occurred (historically) in that area without logging,” he said in an interview with TVW. “There’s no obvious connection right now. It’s pure speculation.”

The Times reported in the wake of the mudslide that the DNR had been relying on an outdated map to determine where loggers could harvest trees above the Hazel slide. The newer map would have likely restricted most of the 7.5 acres that were clear-cut in 2004.

The clear-cut conducted by logging company Grandy Lake appears to have strayed into a restricted zone near the slide that had been protected by the state out of concern that tree removal would increase groundwater flow into the unstable slope.

Goldmark emphasized last week that it was important not to rush to judgment — in either direction — on whether logging played a role in the slide.

Ken Osborn, the local manager for Grandy Lake, defended the work. He said in an interview that the state boundary lines are unnaturally straight, not following the contours of a rugged landscape.

Osborn said those lines are not designed to be strict barriers, and that the more important work is done on the ground to match the boundaries of a cut with the topography of the landscape. He said that was done in this case with the help of an independent geologist.

“To cast this Berlin Wall down there is inappropriate. It’s a guideline,” Osborn said.

DNR records released under public-disclosure law show that an agency worker reported completing a field inspection of the property in October 2004 after the cut was complete. A brief, handwritten note determined that the cut was “in compliance.”

Grandy Lake has not contributed to Goldmark’s campaigns. One of the company’s partners, Merrill & Ring, has donated about $2,500.

Rules tightened

Goldmark’s office touts rule changes made during his time in office, such as action taken by the Forest Practices Board to eliminate a “loophole” that allowed some landowners to avoid scrutiny of their sites in unstable areas. Goldmark’s office chairs that board, while a dozen other members on the panel come from outside the agency.

Mitch Friedman, executive director of Conservation Northwest, considers Goldmark a friend and has seen some bright spots during the commissioner’s tenure. But he’s been disappointed with Goldmark’s reaction to the Oso slide — especially given Goldmark’s fierce talk about the link between logging and mudslides during his 2008 campaign.

“The statements he’s making now seem too defensive and out of sync with the character that he was presenting at the time,” Friedman said. “The public, I think, should expect leadership and a sense of comfort that if logging had a role, that’s going to be aggressively explored and addressed. And the signals that the commissioner has recently sent I don’t really think scratch that itch.”

Friedman said overall that Goldmark has “evolved to where he identifies with the timber more than the environmental side ... He’s not the guy we thought he was going to be or that we hoped for.”

Another environmentalist, Peter Goldman of the Washington Forest Law Center, was even more blunt, saying he believes Goldmark deceived the environmental community to win its support in 2008.

“We do feel there was a lack of a candor with his commitment to conservation,” Goldman said.

Advocates are particularly disappointed in how Goldmark, a rancher from Okanogan County, has handled logging near steep slopes. During the 2008 campaign, Goldmark aired attack ads that linked flooding to steep-slope logging by Weyerhaeuser, which was supporting Sutherland’s campaign.

Goldmark campaigned on a promise to ensure that geologists would examine areas of “moderate” or “high” risk of landslide before approving a cut. Goldmark said last week the agency has faced some budget constraints but currently checks areas that have “significant” risk.

Even when sites do get a geologist review, advocates have questioned the state’s decision to approve logging. The Washington Forest Law Center unsuccessfully opposed a site last year in Snohomish County — not far from the recent mudslide — because it was on slopes so steep that the timber company was looking to use helicopters to complete the job.

While environmentalists are targeting Goldmark now, it was the timber industry slamming him in 2008.

One of its political committees spent $600,000 trying to defeat him, with the largest donation coming directly from Weyerhaeuser. In the final weeks of the campaign, Goldmark made an issue of that money, accusing Sutherland of accepting campaign cash after turning a blind eye to inappropriate logging.

Such campaign contributions were “wrong” and “reprehensible” and “a glaring example of why we need change,” Goldmark said during the campaign.

Goldmark said in the interview with The Times that he doesn’t feel his decisions in office are influenced by campaign dollars.

“It wasn’t something that I felt was really pivotal to my ability to represent the public and act always in the public interest,” he said.

Goldmark had been scheduled to co-headline a political fundraiser last week for U.S. Rep. Suzan DelBene, D-Medina, alongside logging-industry leaders at the Seattle headquarters of Plum Creek timber company. He told a Times reporter before the event that he wouldn’t attend because he did not feel well.

Todd Myers, Sutherland’s 2008 campaign manager, said Goldmark appears to have realized that managing state forest lands is guided by competent DNR scientists and is more complicated than catering either to the environmentalists or to the timber companies. He remembers Goldmark’s anti-logging campaign rhetoric and his pledge to refuse contributions from timber interests.

“I think frankly it was a stupid political claim in the first place,” Myers said. “He said a lot of things that I think he is slowly backing away from.”

Alex Hays, a Republican consultant, said he was initially afraid of Goldmark’s policies when he won the 2008 election. Since then, Hays said he has become “extraordinarily pleased” with how Goldmark has managed lands with pro-timber policies.

“I like what Goldmark has become,” Hays said.

Mike Baker: 206-464-2729 or mbaker@seattletimes.com. On Twitter @ByMikeBaker

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!