Originally published April 13, 2014 at 8:01 PM | Page modified April 15, 2014 at 1:22 PM

For families of St. Helens victims, Oso brings familiar heartbreak

Families and friends of those missing in the 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption know all too well what the Oso mudslide families are going through, and how the pain never goes away.

Seattle Times staff reporter

Keith Ronnholm

Fifty-seven people died when Mount St. Helens erupted, including 20 whose bodies were never found.

CHRIS JOHNS / The Seattle Times, 1981

For many months after the eruption, Ralph Killian, a Lewis County logger, repeatedly searched the devastation for signs of his missing son and daughter-in-law. Christy Killian’s remains were found a year after the disaster, but there was no trace of John Killian.

Courtesy of Connie Pullen

Amateur volcano watchers Bob Kaseweter and his girlfriend, Beverly Wetherald, look at Mount St. Helens from a Spirit Lake cabin the day before the eruption. Kaseweter’s sister cherishes the last photo taken of him.

Oso landslide: Comprehensive coverage of the March 22 disaster and recovery

The Seattle Times

A collection of stories and visuals about the disaster, why it may have happened and the people it affected.

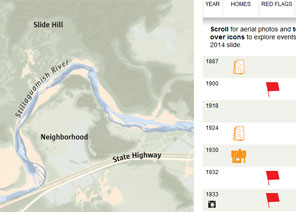

Interactive: Building toward disaster

THE SEATTLE TIMES

Use an interactive to see how, even as warnings mounted, homes kept being built in slide-prone Steelhead Haven.

Remembering the victims

Compiled by The Seattle Times

Read about the lives of the victims.

Interactive map: A detailed view of the neighborhood hit by the landslide

Garland Potts, Cheryl Phillips / The Seattle Times

Use an interactive tool to see the landslide’s deadly path.

TIMES WATCHDOG

![]()

It’s been 34 years since her brother vanished when Mount St. Helens blew.

In certain parts by the mountain, the cascading, pulverized rock was at unbelievable temperatures — more than five times the boiling point of water. Then there was the ensuing landslide that could topple a bulldozer, although most of those who died asphyxiated. The ash simply clogged up their throats, and there was nowhere to hide.

Connie Pullen, of Sandy, Ore., cherishes the last photo ever taken of her brother, Bob Kaseweter. She took it the day before the eruption.

The photo shows Bob, a Portland chemist, and his girlfriend, Beverly Wetherald, a Portland finance worker. She also vanished in the eruption.

They’re on the deck of a cabin at Spirit Lake, right by the volcano. Bob is peering at the towering mountain through a long-lens camera.

Both he and Beverly were amateur volcano watchers.

In recent weeks, the families of the missing on Mount St. Helens have understood very well what — 3½ decades apart — the families of the missing in the March 22 landslide at Oso are going through.

The final death count from the May 18, 1980, blast of Mount St. Helens was 57. Among them were 20 whose bodies were never recovered.

At Oso, the ever-changing figures currently list 36 dead and seven missing.

Pullen is now 71. Bob was 39.

“Sometimes I’m happy that to this day, his body was never found. Sometimes I think, maybe he isn’t really gone,” she says. “I know a lot of people don’t think that way, but I could never give up hope.”

But, really, she knows.

“Of course, I have to accept it,” says Pullen. “If he had to die, that’s the way, I guess. He loved living on the mountain.”

What the Mount St. Helens families can tell the Oso families is what is always said at times like this.

“Time does help,” says Marlene Bickar, of Kelso, whose brother, John Killian, 29, is among the Mount St. Helens missing.

But, she says, “You never heal completely.”

Bickar is reminded of her brother each time she walks in a hallway of her home.

A photo of John from when he was in the Navy hangs on the wall, greeting her.

Bickar remembers how the loss affected her now-deceased dad, Ralph Killian, a logging supervisor.

“My dad never cried, and it’s hard when you see your dad crying,” remembers Bickar. “The devastation was just total. It aged my parents considerably.”

Bickar’s mom, Jeanette, is 81. “She went into a shell, a lot of depression.”

John Killian, a logger, had been married for seven months to Christy Killian, 20.

They had gone camping at Fawn Lake, and John was likely fishing in his rubber boat when the volcano erupted. The lake was known for its great trout.

Christy was likely still sleeping in their tent with their two dogs, says Bickar.

A year after the eruption, skeletal remains belonging to Christy were found. “It was like she was cremated,” says Bickar

As for John Killian, for the likely scenario of what happened to him, one turns to Richard Waitt, a geologist for the U. S. Geological Survey. He has spent years studying the eruption.

“This thing comes crashing. He had a few seconds to react,” says Waitt.

With no trace of her brother ever found, there were no services. “There was no reason,” says Bickar.

They did attend when a memorial was put up at the volcano.

But for Bickar’s parents, gone were the hopes of such joys as seeing their son and his wife have children.

There were three sisters in the family, and John.

“He looked out after us,” says Bickar. “When we were old enough to start dating, it wasn’t with just anybody. It had to be with his approval.”

Just days after the eruption, in a lifelike dream, her brother talked to her, says Bickar. That memory stays with her.

“He came to my room. He told me, ‘Don’t look for me. You won’t find me,’ ”she remembers. “For many months after that, I kept the living room light on.”

Decades later, it’s not just the families, but also the friends of the Mount St. Helens missing who are still affected.

Bruce Johnson, now 66, is a retired mental-health supervisor who lives in Canby, Ore.

He had come to know Bruce Faddis, who was 26 when he vanished in the eruption, some years earlier when they both worked in the firefighting unit at a large ranch resort.

A year after the eruption, says Johnson, he ran across the husband of a sister of Faddis.

The husband told Johnson, “You didn’t know? His plan was to go up there and meet up with Harry R. Truman (the legendary Spirit Lake lodge owner who refused to leave) and go fishing.”

Neither man’s body was ever found.

At the time, Faddis was helping run the golf course at the dude ranch.

“I do think about him. The weird thing was that Mount St. Helens was one of the one or two remaining volcano climbs that I hadn’t done,” says Johnson.

“I had this half-assed plan with a friend that we’d go there, use the east side road system to avoid the barricades (that kept the curious from the volcano) and hike it. Luckily, some older people talked us out of it.”

Then Mount St. Helens blew and Johnson was left pondering fate and luck. Johnson didn’t take the chance; his friend did.

In his later years, Johnson had a photography business. But he has only one photo of his friend, in his fireman’s hat, and it is a faint picture.

“It’s so strange to me, as a lifelong photographer, that somehow I never took pictures that were specifically of my friend,” says Johnson.

That’s another thing about having known the missing.

All kinds of would-haves, should-haves.

Times researcher Miyoko Wolf contributed to this report.

Many thanks to Valerie A. Smith, author of the website “The many faces of Mt. St. Helens,” for her assistance.

Erik Lacitis: 206-464-2237 or elacitis@seattletimes.com Twitter @ErikLacitis

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!