Originally published March 26, 2014 at 9:04 PM | Page modified March 27, 2014 at 12:19 AM

For searchers, tears flow as dig finds only reminders of life

Digging through the mudslide debris can be traumatizing.

Seattle Times staff reporter

MARCUS YAM / The Seattle Times

Darrington volunteer firefighters (from left) Jeff McClelland, Jan McClelland and Eric Finzimer embrace Wednesday after saying a prayer. The three took time out from digging through debris Wednesday to talk about what it’s like to be on the front lines of a grim search.

Oso landslide: Comprehensive coverage of the March 22 disaster and recovery

The Seattle Times

A collection of stories and visuals about the disaster, why it may have happened and the people it affected.

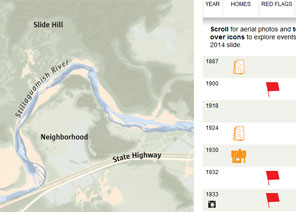

Interactive: Building toward disaster

THE SEATTLE TIMES

Use an interactive to see how, even as warnings mounted, homes kept being built in slide-prone Steelhead Haven.

Remembering the victims

Compiled by The Seattle Times

Read about the lives of the victims.

Interactive map: A detailed view of the neighborhood hit by the landslide

Garland Potts, Cheryl Phillips / The Seattle Times

Use an interactive tool to see the landslide’s deadly path.

TIMES WATCHDOG

![]()

DARRINGTON — Twelve hours on Sunday, 12 hours on Monday, 12 hours on Tuesday. They looked for survivors, but found none.

It gets to them. They talk and they tear up. They can’t help it.

Eric Finzimer, 47, puts his hands to his face. He’s one of this town’s volunteer firefighters who have been on the searches since a mudslide buried a nearby community Saturday.

“I’m sorry, but I’m not sorry,” he says about showing his emotions. “We haven’t had a chance to let loose.”

Three of them, finally taking a break Wednesday afternoon, tell their stories.

On their searches, they’d park on a maintenance road above the mile-wide mudslide.

Wearing heavy-duty gloves, using shovels and pry-bars, hoping search dogs would point to a survivor, they’d dig through the debris. Maybe somebody was alive in an air pocket.

All they found were the reminders of lives.

“We saw some clothing that would fit a 3-year-old, and then some nursery toys. We didn’t know if they were from the same house, or what,” says Finzimer. The slide had literally smashed houses together.

His tears show again.

“You hope you see somebody come walking out of the trees, or one family coming back from a Disneyland vacation, so we can take their names off the list,” says Finzimer.

But no families are returning from vacation, nobody is coming out of the woods.

Finzimer is an EMT who works out of Everett. He’s seen his share of people in dire straits.

He figures that in a week, he’ll start having nightmares, instead of the restless sleep he’s now having. That’s what happened after he handled a particularly gruesome car accident.

Jan McClelland is another of the volunteer firefighters and also an EMT.

“There can be a horrible car accident and we do take pride in being stoic: We will get through this. We will keep our wits about us,” she says.

But this mudslide ... “It was absolutely mind-numbing.”

Says her husband, Jeff McClelland, also a volunteer firefighter: “It looked like an atomic bomb had gone off.”

The couple moved to Darrington in 2008, as Seattle friends, Richard and Louise Yarmuth, owned 80 acres here and had decided to start a goat farm to make cheese. The McClellands live on the farm and run it.

Since the slide, they have been getting up at 5 a.m. to feed and care for the goats, and then have gone on the searches.

The McClellands have become part of this town of 1,400.

One friend lost his wife in the mudslide, and their grandchild at the house is missing, says Jan.

“I kept thinking, ‘I’m going to keep digging, and keep digging, and keep digging until I find his granddaughter,’ ” she says.

She says she knows families don’t want to be left in a limbo in which their loved ones have simply disappeared.

“I lost my daughter 10 years ago in an operation. She was only 19,” she says.

“I know what it’s like to lose a child. It’s heartbreaking for these people. I want them to have closure.”

On Saturday, right after the slide, the McClellands were among the first to respond; they rescued people.

The couple and others tied themselves to some 650 feet of rope — secured to a tree they made sure was stable — and made their way through the muck to reach a man with his right arm mangled.

The man was strapped to a board and eventually airlifted out by helicopter.

“I got a call from one of his relatives. They fixed him. He’s going to be released from the hospital, won’t lose his arm,” says Jeff McClelland.

“That’s so cool. When you’ve saved a life, that’s worth a million dollars.”

He also found some victims’ bodies.

But then, the debris yielded nothing but more debris.

He talks about sometimes trying to relieve the stress by cracking a joke with other searchers.

But they all are aware that from the distance, television news cameras could catch their momentary laughter and it would give a false impression.

Jeff says he found a couple of golf balls and a golf club in the debris, and, again, as a stress reliever, he was going to try and hit the balls in this moonscape.

The fire chief reminded him about the cameras.

These days, the three volunteers say, there are debriefings in which those involved in traumatic events like this can talk it out.

It’s all right, they say they’re told, to talk about their emotions.

On Wednesday afternoon, they do, sitting together, handing out Kleenex, not embarrassed by tears.

Jeff talks about finding a muddy children’s book, “Three Lost Orphan Kittens,” subtitled, “The world is a beautiful place.”

He says: “I dropped to my knees and started crying. The book is right, the world is a beautiful place, although sometimes it doesn’t seem like it.”

Erik Lacitis: 206-464-2237 or elacitis@seattletimes.com Twitter @ErikLacitis

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!