Originally published March 26, 2014 at 8:22 PM | Page modified March 27, 2014 at 1:23 AM

Logging OK’d in 2004 may have exceeded approved boundary

TIMES WATCHDOG: A forest clear-cut nine years ago appears to have strayed into a restricted area that could feed groundwater into the landslide zone that collapsed on Saturday and took at least 16 lives.

Seattle Times staff reporters

Oso landslide: Comprehensive coverage of the March 22 disaster and recovery

The Seattle Times

A collection of stories and visuals about the disaster, why it may have happened and the people it affected.

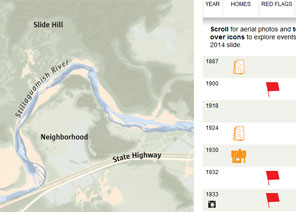

Interactive: Building toward disaster

THE SEATTLE TIMES

Use an interactive to see how, even as warnings mounted, homes kept being built in slide-prone Steelhead Haven.

Remembering the victims

Compiled by The Seattle Times

Read about the lives of the victims.

Interactive map: A detailed view of the neighborhood hit by the landslide

Garland Potts, Cheryl Phillips / The Seattle Times

Use an interactive tool to see the landslide’s deadly path.

TIMES WATCHDOG

![]()

A forest clear-cut nine years ago appears to have strayed into a restricted area that could feed groundwater into the landslide zone that collapsed Saturday.

A Seattle Times analysis of government geographical data and maps suggests that logging company Grandy Lake Forest cut as much as 350 feet past a state boundary that was created because of landslide risks.

The state Department of Natural Resources is supposed to verify a timber company’s proposed cut on the ground and then reinspect the site after the harvest has been taken.

State Forester Aaron Everett reviewed records on the issue Wednesday afternoon and said it appears that a portion of the clear-cut’s footprint extended into the sensitive zone. He said his agency was trying to locate records to show whether it inspected the site after it was logged.

“I was surprised,” Everett said. He will investigate further before concluding whether Grandy Lake went beyond the borders.

Grandy Lake officials have not returned calls seeking comment.

In June 2004, landowner Grandy Lake proposed cutting 15 acres up to the edge of a plateau above the landslide area.

State officials rejected its application because some of the proposed logging fell within the restricted zone — what is called an “Area of Resource Sensitivity.”

Years before, the state had protected this area, which is directly above the landslide area, because scientists were concerned clear-cutting could feed more groundwater into the slope, increasing instability in an area with a history of mudslides. Mature trees can intercept or absorb much rainwater.

A clear-cut impact on groundwater can last for 16 to 27 years, according to a 1988 report by a University of Washington geologist.

Grandy Lake could have harvested in the sensitive area if it first monitored precipitation and groundwater for several years, but the company instead revised its application.

The company proposed leaving out that restricted area and instead cutting a pizza-shape wedge, about 7.5 acres, that abutted the sensitive zone. In August 2004, the state approved the scaled-back plan.

An aerial image from July 2005, however, shows the clear-cut as a larger slice, with its tip going well over the boundary and to the edge of Saturday’s deadly slide, according to state geographical data.

Everett said his agency is gathering records to review what happened and to verify the accuracy of the maps and boundaries. He also wants to send officials to the site of the cut, but the area is currently off-limits due to instability.

He said permitting and reviewing proposed timber harvests can be inexact. For example, Grandy Lake’s original proposal included a small map with a hand-drawn triangle showing the area it wanted to cut. When the company resubmitted its permit application, it used the original map but simply crossed out the portion that was to be left alone, so the new boundaries aren’t entirely clear.

State officials would typically take that map and put it into the state’s digital system, Everett said. An agency worker would visit the site of the proposed cut and make sure the boundaries were correct. Again, that process — typically relying on maps and aerial images instead of GPS coordinates — could be inexact. Landowners who fail to comply with the state’s permit can be fined, Everett said. He said he wants more information before the matter could be referred for enforcement.

Everett said he also wants to consult scientists to see whether the clear-cut could have contributed to the slide. He said trees may have done little to prevent such a deep-seated failure of the hill.

“It’s sort of like the idea that a set of toothpicks are going to hold back a train,” Everett said.

Mike Baker: mbaker@seattletimes.com or 206-464-2729. On Twitter: @ByMikeBaker

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!