Originally published March 26, 2014 at 7:54 PM | Page modified March 26, 2014 at 10:23 PM

Rescuers, survivors reeling from emotional trauma

Survivors, rescuers and even people who answer phones after an event like Saturday’s deadly landslide can experience emotional trauma that may leave them reliving horrific scenes as they struggle to answer unanswerable questions.

Seattle Times health reporter

Oso landslide: Comprehensive coverage of the March 22 disaster and recovery

The Seattle Times

A collection of stories and visuals about the disaster, why it may have happened and the people it affected.

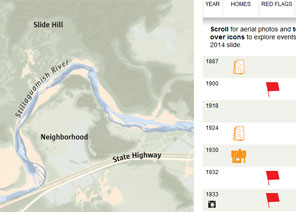

Interactive: Building toward disaster

THE SEATTLE TIMES

Use an interactive to see how, even as warnings mounted, homes kept being built in slide-prone Steelhead Haven.

Remembering the victims

Compiled by The Seattle Times

Read about the lives of the victims.

Interactive map: A detailed view of the neighborhood hit by the landslide

Garland Potts, Cheryl Phillips / The Seattle Times

Use an interactive tool to see the landslide’s deadly path.

TIMES WATCHDOG

![]()

Randy Fay’s voice shook and his eyes clouded Wednesday as he described rescue efforts that plucked a 4-year-old out of the mud in Oso.

Fay, a volunteer with the Snohomish County helicopter rescue team and a grandfather himself, kept thinking: “What if it was Eli?”

Rescuers and residents alike stumble with grief as they cope with the aftermath of the monstrous mudslide that literally turned their world upside down.

Kids, neighbors, friends, family, pets, homes — and life as it was lived before the monstrous mudslide Saturday — all gone.

Survivors, rescuers and even people who answer phones after such a terrible event can experience emotional trauma that may leave them reliving events or scenes as they struggle to answer unanswerable questions, says Mary Schoenfeldt, a disaster stress-management expect helping coordinate support efforts in Snohomish County.

They go through shock, denial, anguish and intense emotions as they attempt to “make sense out of the senseless,” as she puts it.

“What they’ve experienced is so far out of their normal experience that their brain and body are working extra hard to find a place to file away this information,” she says, “but there’s no prior experience to know where that information can go.”

People often go numb, stumbling in gait and speech because “their bodies and brains are working so hard to take in this horrific information,” she says.

Such a “robotic time,” says Pat Morris, senior director of behavioral health for Volunteers of America’s Western Washington Chapter, “is our bodies and our brains trying to insulate us.”

That describes people in his community, says Pastor Gary Ray of the Oso Community Chapel. “People can’t sleep, they can’t eat, they are depressed. The community is dazed.”

Schoenfeldt, an expert in field traumatology services with the Green Cross Academy of Traumatology, has been on the scene of many previous disasters: Sandy Hook Elementary School, Hurricane Katrina, and post-earthquake Haiti.

Physically, people react to disasters, even if they’re only watching on television or reading the news. “Our bodies are absolutely hard-wired to have a physical response,” Schoenfeldt says.

Our heartbeats speed, our eyes constrict to a narrow field, and digestion slows.

People are often very productive after an emotional shock. “Part of their coping mechanism is to stay busy and do what they do well,” she says. “We’re wired to be able to keep going.”

Actually, we all live in a “sort of fiction,” says Dr. Joseph Hullett, a national medical director and behavioral health expert for Optum, a health- and behavioral-services company offering a free emotional-support help line (1-866-342-6892).

“We live in this fantasy that the world is completely safe and everything is going to be all right ...,” he says. Then, “something rips that fantasy from our minds, and all of a sudden we realize it’s not safe.”

First responders are the most vulnerable to stress disorders, Hullett says. But anybody can feel the stress: “You’re sitting in the Starbucks, someone comes in and they’ve lost people in their family. You’re like a first responder, maybe not seeing body parts, but you’re seeing loss in your head.”

Such a bystander may experience grief over “the loss of certainty, of predictability — the loss of the feeling of comfort in your life.” And they may feel they don’t deserve to have such stress reactions, these experts say, or feel survivor guilt.

What do those affected need? All these experts say the same thing: They need to know what they’re feeling is normal, that people are there to listen. And support down the road, when the public spotlight dims.

That’s just what Pastor Ray of the Oso Chapel plans for weeks and months to come. “Most people just need a shoulder, empathy and ear,” he says. “People really benefit from having good folks around them. Not to take over, but to just be there.”

Carol M. Ostrom: costrom@seattletimes.com or 206-464-2249. On Twitter @costrom

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!