Originally published March 25, 2014 at 7:59 PM | Page modified March 26, 2014 at 2:52 PM

A small town’s embrace: In Darrington, ‘we help people out’

In the little town of Darrington, residents pride themselves on taking care of each other. That way of life has been amplified by the deadly mudslide just 12 miles down the highway.

Seattle Times staff reporter

MARCUS YAM / The Seattle Times

Darrington Mayor Dan Rankin crosses the road Monday after a news conference. “I’m trying to hold it together all day long,” he said later at a town meeting.

Oso landslide: Comprehensive coverage of the March 22 disaster and recovery

The Seattle Times

A collection of stories and visuals about the disaster, why it may have happened and the people it affected.

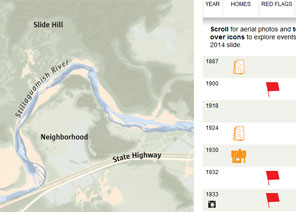

Interactive: Building toward disaster

THE SEATTLE TIMES

Use an interactive to see how, even as warnings mounted, homes kept being built in slide-prone Steelhead Haven.

Remembering the victims

Compiled by The Seattle Times

Read about the lives of the victims.

Interactive map: A detailed view of the neighborhood hit by the landslide

Garland Potts, Cheryl Phillips / The Seattle Times

Use an interactive tool to see the landslide’s deadly path.

TIMES WATCHDOG

![]()

DARRINGTON — What you notice about the high-school basketball gym — “Home of the Loggers” — is the beautiful woodwork, from the bleachers to the walls.

No plastic trimmings here. You half expect Gene Hackman to show up with his “Hoosiers” team.

The gym is part of the Darrington Community Center, which has been filling up this week with clothing, blankets, sleeping bags, cots, toys, books, boxes and boxes of food, even homemade cupcakes.

“We take care of our own,” they just keep telling you in this small town of 1,400, where the snowy peaks of the Cascades hover over the backyards.

Oso, where Saturday’s tragic mudslide wiped out dozens of houses, is just 12 miles west on Highway 530. The Oso kids are bused here to school, which resumed Tuesday.

The townspeople built the center and the gym by themselves in 1954.

Diane Boyd, president of the center and librarian at Darrington High School, points to the shiny floor. “We just put it in. The local mill, kids helped.”

Volunteers say that on Monday night, just one person slept overnight on the cots for evacuees. There was no reason to use the cots when families in Darrington opened up their homes.

LoAnna and Kris Langton and their four children, whose rental house in Oso ended up chest-deep in water, mud and debris, are staying with Billie Moore, 83.

Moore has lived in Darrington since she was 3. She knew the Langtons from Mountain View Baptist Church here, and Moore has a four-bedroom house.

“Here, we help people out,” she says.

The local economy has been struggling.

The Darrington division of Hampton Lumber Mills, the Forest Service and the school district are the biggest employers, says Boyd. But the old logging jobs have gone away.

Still, the population of the town remains stable; it’s actually bigger by a couple hundred people than in 1970.

Even younger residents don’t seem particularly eager to leave for the big city.

Helping sort food at the community center is Bailey Neidigh, 16, a junior at the high school.

“I hate the big city. I feel so lost. I like the seclusion here,” she says.

And, says Bailey, “Everybody knows everybody.”

It seems everyone in Darrington knew somebody who was in that slide.

“My best friend’s dad is missing,” says Bailey. “I can’t believe it.”

The closeness of the community is shown by something informally called the “Funeral Dining Committee,” although, as Frankie Nation-Bryson, 82, explains, “We don’t have a boss, we don’t have a president.”

The two people who started the tradition in 1950 were Janet Cabe, now 81, and her late husband, David Lee Cabe.

Back then, she was an 18-year-old bride and family from Hoquiam had come to Darrington for a funeral.

“The only cafe in town had burned down and there was no place for them to eat,” remembers Cabe. “My husband said, let’s just have them come over to the house and we’ll make sandwiches and stuff. It grew from that, bigger and bigger.”

Now, on the average a couple of times a month, there is such a dinner. Two a month, 64 years, that’s more than 1,500 such dinners.

Some people who lived in Darrington and moved away specifically request their funeral be held in their old hometown, says Cabe.

Yes, she says, as the fatality numbers keep increasing in the Oso tragedy, she expects the dinner committee to be plenty busy.

“We’ll do what we can,” says Cabe.

At a town meeting held at the gym on Monday night, Mayor Dan Rankin told a crowd of some 400 to 500 who had shown up that they’d get through the tragedy, “As long as we get up in the morning ... go to work ... go to school.”

Rankin runs a one-man sawmill operation and, when elected in 2011, he beat incumbent Joyce Jones in a close race that was marked by its civility.

He called Jones to tell her that he was putting up 10 yard signs, just to make sure she wasn’t surprised and maybe offended at such aggressiveness. In turn, when Rankin was ahead by nine votes — 184 to 175 — with only six votes left to be counted, she graciously conceded and a recount was avoided.

Monday night, Rankin choked up before his constituents.

“I’m trying to hold it together all day long,” he said.

That town meeting ended with a dozen and half members of the Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe, which has a membership of about 200, presenting a check for $5,000.

Then, using drums, they lay a blanket in front of them and chanted what in English is approximated as “help the children.”

Members of the tribe then walked to the blanket and put down some more money.

The Darrington residents watched from the bleachers, and then, slowly, a number of them walked down to the gym floor and also put down some money.

Among them was Matt Wright, 36, a big guy with calloused hands who’s a truck mechanic at NW Washington Compost in town.

“Been here all my life,” he says about his little town.

“You help out.”

Erik Lacitis: 206-464-2237 or elacitis@seattletimes.com Twitter @ErikLacitis

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!