Originally published March 23, 2014 at 7:38 PM | Page modified March 24, 2014 at 12:06 AM

Site has long history of slide problems

The area of Snohomish County hit by a mudslide Saturday has long been susceptible to slides and floods, and the state has previously taken steps to try to stabilize it.

Seattle Times staff reporters

Oso landslide: Comprehensive coverage of the March 22 disaster and recovery

The Seattle Times

A collection of stories and visuals about the disaster, why it may have happened and the people it affected.

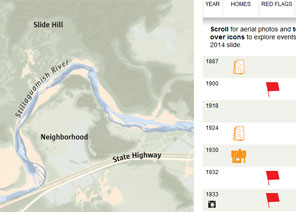

Interactive: Building toward disaster

THE SEATTLE TIMES

Use an interactive to see how, even as warnings mounted, homes kept being built in slide-prone Steelhead Haven.

Remembering the victims

Compiled by The Seattle Times

Read about the lives of the victims.

Interactive map: A detailed view of the neighborhood hit by the landslide

Garland Potts, Cheryl Phillips / The Seattle Times

Use an interactive tool to see the landslide’s deadly path.

TIMES WATCHDOG

![]()

The pocket of Snohomish County hit by a mudslide Saturday has long been susceptible to slides and floods, bedeviling engineers who for decades have built dikes, rock buttresses and drainage systems in hopes of managing the river and stabilizing the hills.

For the North Fork of the Stillaguamish River — clean and clear in the early 1900s, when it became known as an ideal steelhead stream and was fished by the likes of Western novelist Zane Grey — there was the flood of 1933, the slide of 1967, the slide of 2006.

The slide eight years ago dispatched a wall of mud down the same hill that buckled this weekend. “This is the very same mass of rock and dirt,” said Tim Walsh, geologic hazards chief for the state Department of Natural Resources. “It just moved again.”

“Landslides often occur in the same place over and over.”

The Stillaguamish, no longer so clean and clear, has changed paths repeatedly while the wet hills have loomed as a constant threat to homeowners and to drivers on Highway 530.

Wayne Gilbert has never forgotten the January morning in 1967 when he woke early to fish the Stillaguamish with his father and discovered there was no water. He was 13 at the time, and ran back to the house shouting, “Dad, Dad, the river is gone!’’ His father followed him out of the house to the river bank. What they saw in the dark was a muddy riverbed, with fish flopping out of water and others swimming in small pools. Gray-blue clay plugged the river and formed a lake above.

When he heard about Saturday’s slide, Gilbert wondered why so many people seemed surprised. “They keep saying they haven’t seen anything like it in 30 years,’’ he said. “Go back further.’’

Sixteen months ago, the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) completed a $13.3 million project, called the Skaglund Hill Permanent Slide Repair, to secure an area just west of Saturday’s slide, on the opposite side of the Stillaguamish River.

That project covered about a half-mile stretch of Highway 530, from mile marker 36.25 to 36.67. It secured a hill south of the river. Saturday’s slide collapsed a hill north of the river and sent mud crashing into the Stillaguamish and across Highway 530 between mile markers 37 and 38, according to WSDOT.

The Skaglund Hill project traces to February 2006, when a state maintenance crew found a “rapidly growing crack” on Highway 530 caused by slope movement, according to WSDOT records. The month before, a mudslide had unsettled residents by plugging the river’s North Fork, which responded by cutting a new channel. That new channel threatened homes in the Steelhead Drive area, the same neighborhood hit this weekend.

It took about six years to finish the Skaglund Hill project. The work included installing drainage pipes to keep the soil from getting too soaked and the planting of trees and shrubs along the hillside.

At the bottom of the hill, between the roadway and river, workers built a rock buttress.

Travis Phelps, a WSDOT spokesman, said the buttress works like this: Say you’ve got a bowl of pancake batter. You tilt the bowl and the batter starts working its way to the edge. If you put your hand on the bowl’s lip, you stop the flow. The buttress works like your hand, providing support for the entire hillside.

Workers also built a wall farther up the slope, for additional support, Phelps said. Some wetlands were lost in the project, so to compensate, WSDOT restored an 18-acre wetland elsewhere in the county.

Engineers have wanted to avoid a repeat of 1967, when a hill on the Stillaguamish River’s north bank lost a slice of clay about 800 feet long and 300 feet high, according to news reports at the time. That slide occurred just a little to the east of this weekend’s slide, Wayne Gilbert says.

The 1967 slide damaged or flooded at least 25 cabins in a development called Steelhead Haven. One resident told a reporter back then, “The whole mountain just slid into the river,” a description echoed this year by Robin Youngblood, who saw a 25-foot-high wall of mud descending on her home Saturday: “Then it hit and we were rolling.”

Throughout the years there have been small slides to go with the big ones. The area that collapsed almost a half-century ago was known informally as “Slide Hill” — and that was before the 1967 slide.

Barry Galde, who was 12 when he lived along the river, woke up that morning to a roaring sound. He jumped out of bed and called his father. Together they went to the railroad tracks.

The tracks were covered in mud. His father saw that some people were trying to catch fish in the small pools in the riverbed and yelled for them to get out of the way in case the mud dam broke.

Although cabins suffered damage, no one was injured in the 1967 slide. “But if it had been two hours later, the story would have been different,” says Barry’s brother, Garry Galde. “It was a popular fishing spot.”

Science reporter Sandi Doughton contributed to this report. Nancy Bartley: nbartley@seattletimes.com or 206-464-8522; Ken Armstrong: karmstrong@seattletimes.com or 206-464-3730

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!