Originally published January 21, 2012 at 6:00 PM | Page modified March 22, 2013 at 4:50 PM

Corrected version

State wastes millions helping sex predators avoid lockup

Washington's civil-commitment program that shields society from the worst sex offenders is burdened with unchecked legal costs and secrecy, The Seattle Times has found.

Seattle Times staff reporter

DEAN RUTZ / THE SEATTLE TIMES

On McNeil Island: The state's worst sex predators live in the Special Commitment Center. They've already served prison terms but are locked up indefinitely to shield society. Some commitment cases stretch out years, racking up bills for public defenders and psychologists.

DEAN RUTZ / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Psychologist Richard Wollert earned $1.2 million in two years as a defense expert in U.S. sex-offender cases.

DEAN RUTZ / THE SEATTLE TIMES

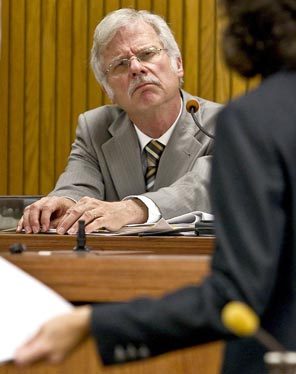

Controversial methods: Richard Wollert explains theories he developed about the likelihood of a sex offender to reoffend. In two Washington cases, judges found Wollert's testimony lacked credibility.

Brooke Burbank says offenders' pricey defense is unwarranted.

MIKE LEVY / THE SEATTLE TIMES

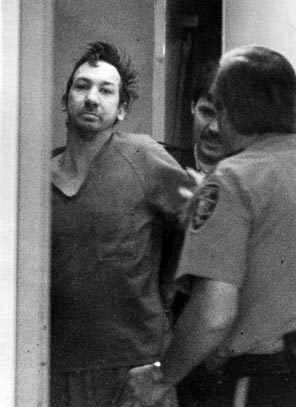

Earl Shriner, above, who had previously served prison time for kidnapping and sexually assaulting teen girls, was arrested for savagely mutilating a boy in 1989. His case inspired the 1990 Community Protection Act, which led to the creation of the state's Special Commitment Center. From left: repeat sex offenders Lawrence Williams, Jeffery Wilson and Jack Leck.

DEAN RUTZ / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Above: Lawyer Robert Naon, above center, hired psychologist Richard Wollert, right, to determine how likely child molester Jack Leck, left, was to commit another sexually violent act. Right: Psychologist Robert Halon waits to board a ferry bound for McNeil Island. At far right, Theodore Donaldson testifies for serial rapist Kevin Coe in Spokane. Halon and Donaldson were fired in 1996 from a contract with the state of California to conduct civil-commitment evaluations.

Who can be confined?

To be indefinitely detained at the Special Commitment Center, an offender must meet the legal definition of a "sexually violent predator":

"Any person who has been convicted of or charged with a crime of sexual violence and who suffers from a mental abnormality or personality disorder which makes the person likely to engage in predatory acts of sexual violence if not confined in a secure facility."

Source: Revised Code of Washington

Part One: Expert Costs

State wastes millions on sex-predator legal bills

Sex offenders' legal costs were kept secret from public

Timeline: Evolution of Washington's troubled civil-commitment program

Graphic: How a sex offender gets committed to McNeil Island

Expert costs: source documents

Part Two: Predator Island

Waiting on predator island: Chronic delays drive up cost

Sex offenders could get trials annually, driving up the legal bills

U.S. map: Where sex predators are detained

Predator island: source documents

Part Three: Worst Case

Swayed by a psychologist, jury frees 'monster' who attacks again

Part Four: Challenges

Tiny office says it can save state money on sex-offender defense

![]()

Across the bone-chilling waters of the Puget Sound, far from any schoolyard or nightclub, sits a small island reachable only by a high-security ferry.

Two miles inland, behind coils of concertina wire, the state of Washington detains its most reviled and dangerous citizens — child molesters, compulsive rapists, sexual sadists — all with a litany of crimes, addictions and mental disorders.

Here on McNeil Island in the Special Commitment Center, some 280 sex offenders who've already fulfilled their prison sentences continue to be locked up indefinitely as a way to protect society.

That protection, known as civil commitment, comes at a high public price.

In 1990, Washington became the first state to pass a civil-commitment law, detaining offenders who are deemed by a judge or a jury to be too dangerous to set free.

Since then, the controversial program has been plagued by runaway legal costs, a lack of financial oversight and layers of secrecy, The Seattle Times has found.

The state has little or no control over the $12 million a year in legal bills — nearly one-quarter of the center's budget. This results in overbilling and waste of taxpayer money at a time when the agency overseeing the center, the Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS), faces deep budget cuts.

The civil-commitment law has created a cottage industry of forensic psychologists who have been paid millions of dollars for evaluating sex offenders and testifying across the state.

The Times determined that the busiest and best-paid experts include two psychologists who were fired in California, another who has flown here at state taxpayer expense from his New Zealand home, and one who has been paid $1.2 million over two years, some of it for work on cases in which judges questioned his credibility.

Defense teams have hired multiple psychologists — each charging tens of thousands of dollars — for a single case. In at least eight King County cases, the public paid for three or more forensic experts to evaluate the offender or testify for the defense. The state typically hired one expert. Both sides accuse each other of expert shopping.

Defense lawyers repeatedly delay trials, seeking continuances and appeals, which push costs up. In King County, it takes on average 3.5 years for a commitment case to go to trial; several have taken close to a decade. Meanwhile, offenders are held at McNeil Island, by far the most expensive confinement in the state at $173,000 a year per resident.

It takes up to $450,000 in legal costs to civilly commit a sex offender in King County. Defense outspends prosecution almost 2-to-1, says David Hackett, prosecutor in charge of civil commitments.

How some of the money is spent is a mystery. King County judges, at the request of defense attorneys who cited lawyer-client privilege, have indefinitely sealed hundreds of documents authorizing funds for defense experts. The Times fought successfully to get many of these records unsealed, which included psychologists' names and their fees.

Hackett said the program needs a financial overhaul. "It's a morass," he said. "We've left the door to the candy store wide open."

Public fear, outrage

In the woods near Tacoma in 1989, a repeat sex criminal named Earl Shriner raped a 7-year-old boy, severed his penis, choked him and left him in the dirt, barely alive.

The grisly crimes outraged the public. Shriner had been released two years earlier after serving 10 years for kidnapping and sexually assaulting two teenage girls. At the time, some officials warned he was too dangerous to be freed.

Largely in response to the Shriner case and another case in which a Seattle woman was raped and killed by a sex offender in a work-release program, lawmakers in Olympia passed the 1990 Community Protection Act. It allowed the state to use the civil courts to confine the most dangerous sex offenders. Nineteen other states have since passed legislation modeled on Washington's law.

"It's a highly controversial law," said Kelly Cunningham, superintendent of the McNeil Island facility. "You are talking about restricting someone's freedom after they have served their prison sentence, not for what they have done, but for what they might do."

Advocates of the law say it is designed to protect the public from the worst of the worst — sex offenders who, if released, would rape, molest and even kill.

Despite being upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court, civil commitment has faced continuous attacks. Critics call it double jeopardy, punishing a person twice for the same crime, a grave violation of constitutional rights.

A public defender in Snohomish County, Martin Mooney, who handles commitment cases, says the entire process is flawed. He said legislators wrote a law that creates a broad, new definition of mental illness that applies to sex offenders, then uses psychologists to forecast who might reoffend.

"It's asking psychologists to be able to accurately say who are really the dangerous guys and who aren't. And I don't think they can do it accurately either way," Mooney said.

"There are experts, on both sides, who have taken pure advantage of this," he said. "Now who do I ultimately blame? Olympia. They signed up for it."

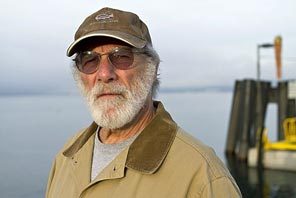

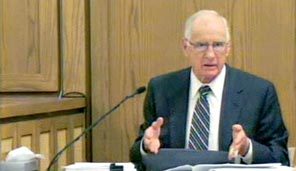

Theodore Donaldson, 84, a psychologist who has been paid millions over the years testifying for Washington and California sex offenders, agrees that experts have taken advantage of the law.

"Two cottage industries have resulted from this law: the experts that can sprinkle their holy water, and the tools to measure risk assessments," he said.

The state tries to lock away only those sex offenders it believes are most dangerous. In 2010, of the 1,187 up for release from prisons and mental institutions, just 17 were referred for civil commitment, according to the Department of Corrections.

The Attorney General's Office handles all the civil-commitment cases except for King County's, where the Prosecutor's Office litigates them. The county has about 30 percent of all commitment cases.

Offenders are entitled to a proper defense. If they are indigent, which almost all are, the public pays for their defense lawyers, paralegals, psychological experts and investigators.

Kenneth Chang, a public defender who represents sex offenders in King County, said defense costs may appear higher, but the defense has more work to do than the state.

"The state's case comes packaged; our case we have to create from scratch," he said.

And until recently, this pool of money appeared to be limitless, with forensic experts naming their price.

How high is the risk?

In a Kitsap County courtroom several months ago, Richard Wollert, a gray-haired psychologist with a bushy mustache, smiled at the jurors, then softly talked to them about a repeat child molester facing civil commitment.

Wollert said that Jack Leck, at one time, may have suffered from pedophilia, a personality disorder in which the person is sexually attracted to children, but he now no longer had it.

Leck had sexual contact with seven boys in the 1980s in Alaska, and lived behind bars off and on throughout his adult life. Seven months after his release in 2002, Bremerton police caught him with dozens of images of child pornography on a computer at an office where he did volunteer work.

In court, Leck, a tall, thin man who gave his age as 59, admitted to jurors he still had an interest in boys but that he would never again touch that "forbidden fruit."

Civil commitment is basically a two-step process. A psychologist must first determine if someone like Leck suffers from a mental abnormality or personality disorder. And if so, determine whether it makes him more likely than not — more than 50 percent — to commit a sexually violent act in the future.

The state's expert, Dale Arnold, a California psychologist, explained to the jury that Leck did suffer from pedophilia and believed Leck would likely find new victims if he wasn't locked up.

Leck hired Wollert on the taxpayers' dime. The Vancouver, Wash., psychologist has earned $1.2 million over two years as a defense expert in civil-commitment cases across the country, pushing his own science and theories. About half of his business comes from Washington.

Wollert had a contract with Oregon's Multnomah County to provide treatment to sex offenders on probation and parole. In 2001, county employees criticized Wollert for incomplete assessments, inadequate treatment guidelines and poor record keeping. The county and Wollert agreed to end the contract.

In the Kitsap County courtroom, Wollert explained that his opinion was based on Leck's own statements that he no longer had fantasies about boys.

Wollert was relying on Leck's words, even though he knew Leck was a habitual liar and had even been deceptive during the psychological evaluation.

"I don't believe the intensity of the urges are what they were in the 1980s. ... I believe he has the ability to control his behavior," the psychologist said on the stand.

In his evaluation of the offender, Wollert credited Leck for not obtaining child pornography for the past eight years. But Leck had been confined to prison or the Special Commitment Center the whole time.

Psychologists have no precise way to determine if any specific offender will commit a violent sex crime in the future, but the law hinges on this. Experts on both sides typically rely on a 10-question assessment tool, the Static 99 and its updated versions, to provide the best guidance on risk. It is the most widely used and accepted tool to evaluate adult male sex offenders.

Psychologists score offenders on criteria such as age, number of sex crimes and sex of the victim. That score is plugged into an actuarial chart that shows recidivism rates of groups of previously convicted sex offenders with similar characteristics. Washington's criteria for commitment includes that the offender be more likely than not to commit a new violent sex crime.

Using the Static 99 and his clinical judgment, Arnold said that Leck was in a moderate- to high-risk group, one with an up to 49 percent chance of reoffending over 10 years.

Wollert disagreed.

A skeptic of the Static 99, he modified it, removed key questions and called his new tool the MATS-1.

For example, he removed the question asking if the victim was a stranger. With the Static 99, a yes answer pushed an offender into a group that was considered a higher risk to reoffend.

R. Karl Hanson, the creator of Static 99 from Ottawa, Ontario, has criticized Wollert's methods, saying he misrepresents statistics and hasn't done the research to validate his own theories.

"More troubling is that he appears to be relying on my research to suggest that I agree with his analysis, when in fact I disagree," Hanson said in a 2008 affidavit in a Franklin County court case.

Using his MATS-1, Wollert told the jury that Leck fit a category of offenders who have only a 23 percent risk of reoffending over an eight-year period.

After hearing from the dueling experts, the jury decided — Leck needed to be committed to McNeil Island.

In a phone interview, Leck scoffed at what taxpayers had to dole out for experts to predict the odds that he would commit future sex crimes. Wollert's bill came to $121,000 for this trial and Leck's previous mistrial, Kitsap County invoices show. The Attorney General's Office said its experts billed about $45,000.

"It would have been cheaper if they would have hired a gypsy and some fortune tellers," Leck said. "I would have had just as much luck."

"Mumbo jumbo"

Wollert often finds himself under attack for his changing theories about recidivism and his self-made assessment tools.

For example, in 2005 he testified that, according to his own research, sex offenders older than 25 fit in a group that had less than a 50 percent chance of committing a new violent sex crime.

Amy Phenix, a forensic psychologist in Pullman who over the years has worked for both the state and defense attorneys, said Wollert almost always finds a reason why an offender doesn't meet criteria for commitment.

"His reports are a gross misrepresentation of risk — it's mumbo jumbo," she said.

Wollert declined to comment.

In two Washington civil-commitment cases, judges found that Wollert's testimony lacked credibility.

Chelan County Superior Court Judge Chip Small criticized Wollert for a lack of objectivity in a 2009 case. "Dr. Wollert testified that if an individual were to commit 100 rapes over greater than a six-month period they still would not likely fit the definition of paraphilia (deviant sexual disorder)," Small wrote.

Wollert was paid about $60,000 in that case, Chelan County records show.

He also has offered unorthodox reasons why some sex offenders shouldn't be committed. Take the case of Keith Elmore, who assaulted and kidnapped a woman. Elmore had cannibalistic fantasies about eating a woman in order to become one; he even formally changed his name to Rebecca.

"His sexual arousal came from fantasies of killing women, cutting up women and eating them," said Brooke Burbank, state assistant attorney general in charge of civil commitments. "Clearly he's an individual who had mental disorders and met the statute."

The defense hired Wollert to evaluate Elmore. During their interview, the psychologist asked Elmore if he had ever killed a large animal or cut up a roast beef, court records show. Elmore replied no. Wollert later said one reason that Elmore didn't meet criteria for commitment was because he lacked the skills to carry out his fantasies of cutting up women.

Wollert was paid more than $60,000 over several years in the case.

Messy billing system

No judge, county administrator or state official can have a complete picture of the costs, which creates leeway for defense experts to bill for questionable expenses.

Legal bills are funneled through three different government agencies. A county judge approves an order for a defense expert, which sometimes is sealed. Then the defense expert submits an invoice not to the judge but to county officials where the trial is taking place. The county pays the expert, then later gets reimbursed those costs by the state Department of Social and Health Services.

When the Times asked for legal costs of particular sex offenders, DSHS couldn't provide it due to its accounting system and the way it processes invoices.

Cath Repp, who retired as a financial analyst at the Special Commitment Center, said county court administrators weren't scrutinizing invoices, which often included bills from multiple lawyers and psychologists with no itemization. "It got too difficult to track," said Repp, who sometimes caught errors. "Some of the explanations are cryptic ... it's hard to know what they were for."

This multitiered pay system has never been audited.

"We're not being as accountable as we should be with taxpayer dollars," said Cunningham, the center's superintendent since 2009.

"One of the struggles we've had is the fact that we're required to pay for all the legal costs. ... It puts us in a precarious situation — when you push back, you can be accused of interfering with due process."

The Times reviewed a sampling of itemized defense bills in King County, and found that nine out of 15 invoices had inconsistencies or errors. When comparing bills for conference calls between psychologists and lawyers, the lengths of time and many of the dates didn't match.

This discrepancy also was found in bills submitted by defense psychologist Wollert and lawyer Robert Naon, who defended Leck in Kitsap County. Wollert was paid thousands of dollars for consulting with Naon on dates that the lawyer didn't include in his invoice. And Naon was paid for conference calls that Wollert didn't report on his invoice.

"I underbilled significantly," Naon said. "I tried to reflect it accurately; maybe I got some dates wrong."

After being told about the discrepancies, the judge in the case is now looking into the bills.

With no one agency overseeing the legal costs, Burbank said, "it's essentially a blank check. ... Experts are billing the court, the court is approving it and DSHS is forced to pay it.

"It's just a free-for-all."

Recycled evaluations

With little control or oversight on costs, attorneys have hired forensic experts who submit inflated bills, recycle evaluations, and even live half way around the world.

Douglas Boer, a psychologist in New Zealand, has worked as a defense expert in at least eight King County commitment cases.

In a 2009 case, Boer made nearly $29,000 for his work for Bob Pugh, who had been convicted of two cases of child molestation and admitted to molesting 10 other children. Boer wrote that Pugh didn't meet criteria for civil commitment because "he admitted to the sexual interactions, but added that he did not find the interactions sexually stimulating."

Pugh lost his case.

Robert Halon, a psychologist from California, overbilled the state in 2009 for a first-class flight and a $1,074 car rental, records show. In this instance, a Special Commitment Center financial analyst caught the overcharge.

Halon said he was unaware of state limits for travel reimbursement. "I send in receipts and then they pay or they don't," he said.

Halon's practices have been called into question before. His license was on probation for 2 ½ years in 1999 after he failed to report suspected child abuse, according to records of the California Board of Psychology.

He and another psychologist, Theodore Donaldson, were fired in 1996 from a contract with the California Department of Mental Health to conduct civil-commitment evaluations.

Donaldson "had problems with clinical diagnosis, report writing skills, risk assessments and clinical conclusions," Phenix, their supervisor at the time, later said.

Shortly thereafter, Donaldson and Halon sent a letter to California public defenders, offering their services as civil-commitment experts. They have worked exclusively for the defense since.

Donaldson's business flourished. By 2007, he testified, he had performed 459 evaluations in California, and rarely found offenders needing civil commitment. In Washington, he had completed 80 evaluations and determined none of the offenders required commitment. Donaldson, of Florence, Ore., said he made about $390,000 in 2008.

The Times studied several of Donaldson's evaluations in Washington cases and found instances in which he used the same wording in large sections of different reports, sometimes just changing the offender's name. For example, large chunks of a 2007 evaluation of a King County rapist appeared word for word in the reports for three other offenders.

"It's unethical," Phenix said. "It's the same argument for every case."

Donaldson acknowledges his evaluations are similar. "The parts that are redundant deal with the legal issues and the science issues," he said.

In one of Donaldson's invoices, he billed $1,200 for eight hours of interviewing an offender. But his written report said the interview lasted for only four hours.

Donaldson said that bill likely reflected a time he included travel as part of his charge for interviewing. "I was careful not to double-bill for anything," he said. While invoices for state experts aren't typically as high as for the defense, some have stood out. Harry Hoberman, a psychologist from Minnesota, charged $22,000 to evaluate a sex offender and write a report in 2008, according to DSHS records.

"Cadillac" defense?

Another reason that legal costs have been so high is that judges have allowed defense attorneys to hire several experts, at public expense, for a single case. The prosecution typically hires one expert.

The general rule for those facing civil commitment: They are entitled to a lawyer and a forensic expert. But a judge may approve additional lawyers and experts.

In Pierce County, for example, jurors couldn't decide whether Jeffrey Wilson, who had molested several young girls, should be civilly committed. When the case was refiled, Wilson's lawyers hired five experts at a cost of more than $77,000 in 2008 and 2009, DSHS records show.

Two of those experts, an Edmonds psychologist and a Canadian therapist, billed for tens of thousands of dollars in costs not permitted by state rules, such as creating a community based support group for Wilson in lieu of being confined to McNeil Island. DSHS objected to those costs but a judge ordered the agency to pay most of the bill, $45,000.

Attorneys representing Wilson would not comment.

Burbank said many sex offenders like Wilson have gotten a "Cadillac" defense. "There's nothing in the constitution or any due-process that requires an individual be entitled to the best defense or multiple experts or the most expensive defense," she said.

One King County commitment case with multiple defense experts involved Lawrence Williams, who started raping women at 14.

Williams' lawyers hired at least four experts. They hired both Donaldson and Halon in summer 2003. On the same day in January 2004, a judge approved two more experts, one from New York, the other from New Jersey.

The court approved $21,280 for Donaldson and $19,765 for Halon.

Last summer, the state, with Cunningham's help, enacted legislation limiting each side to one expert per civil-commitment case. But Burbank said the change likely will do little to curb costs because defense attorneys can still hire more experts with a judge's approval.

Porn, coke smuggled in

Despite the four experts, Williams lost his case and was committed in 2004. A year later, hoping to get out, he hired a new expert, Stephen Hart, a Canadian forensic psychologist who charges one of the highest rates, $437 an hour.

He wrote that Williams suffered from a personality disorder, but had abstained from drugs and any sexually deviant behavior while confined, and qualified to live in a setting with fewer restrictions.

But Williams had duped his expert. With the help of a commitment center staffer and a nurse, Williams sneaked porn videos into the center, federal court records show. He also paid a guard to smuggle in crack cocaine.

Williams was caught and is serving a nine-year drug sentence in federal prison. When he completes his time, he will return to the most expensive confinement in the state, McNeil Island.

Christine Willmsen: 206-464-3261 or cwillmsen@seattletimes.com. On Twitter @Christinesea. Researcher Gene Balk contributed to this report.

CLARIFICATION: The original article, published Jan. 21, 2012, stated that a consulting-services contract between Richard Wollert and Multnomah County, Oregon, was cancelled by the county. In fact, the contract was terminated by mutual agreement of the parties.