|

|

|

| Your account | Today's news index | Weather | Traffic | Movies | Restaurants | Today's events | ||||||||

|

|

Tuesday, July 13, 2004 - Page updated at 12:46 P.M. Airport-security system in U.S. riddled with failures Copyright 2004, The Seattle Times Company By Cheryl Phillips, Steve Miletich and Ken Armstrong

But more than 2-1/2 years after it was created, the Transportation Security Administration itself needs a fix. As Sept. 11, 2001, grows more distant, airline passengers complain more about long lines than feeling vulnerable. Yet lax security and low morale seep through the federal agency responsible for protecting them, The Seattle Times has found. Management memos, as well as firsthand accounts of more than 100 screeners and supervisors interviewed by The Times, depict an agency in crisis. Even as government officials warn of another attack, TSA is ill-prepared to meet that threat. In Seattle, airlines were caught loading unscreened luggage onto planes. In Los Angeles, a supervisor waved around a passenger's gun, sending one screener running for cover. And in Houston, one lapse so alarmed screeners they complained to Congress.

TSA managers huddled to discuss the expected deluge of luggage once the belt was fixed. Their solution? Examine what bags you can, the managers told screeners, and send the rest through — unscreened. The screeners, stunned, didn't say anything. But they didn't go along, either. They inspected every bag they touched, using scanning machines or hand searches to look for bombs or other weapons. Meanwhile, two managers grabbed at least 80 unscreened bags and heaved them onto a conveyer belt headed for the bellies of waiting planes. "I thought to myself, 'You sorry-ass dog. Your ass is not on that aircraft, how do you know what's in that bag?' " one screener told The Times. Every day, TSA balances security with the need to move more than a million airline passengers. On March 12, Houston screeners say, the TSA sacrificed safety for speed, endangering hundreds of travelers.

In response to a Times inquiry about the incident, TSA officials wrote in an e-mail that the improper baggage screening "would, if true, constitute an unacceptable deviation from TSA standard operating procedures." The e-mail, from TSA spokesman Mark Hatfield, said witnesses should report such activity to TSA management or the ombudsman's office for investigation. The Houston lapse, as large as it was, has never been publicly reported. The Times discovered it while interviewing scores of screeners and supervisors. Most insisted upon anonymity, afraid of being punished. In most instances, The Times was able to corroborate their accounts through other TSA employees or documents. Many screeners took the job to help protect their country in a time of danger. Now some say they feel compromised by a workplace with a high injury rate, low morale, long hours, heavy-handed managers, inconsistent orders and other obstacles. As a result, they say, public safety is at risk. Managers, meanwhile, have pleaded for more people, asking the agency in e-mails and memos to "immediately abandon" cuts.

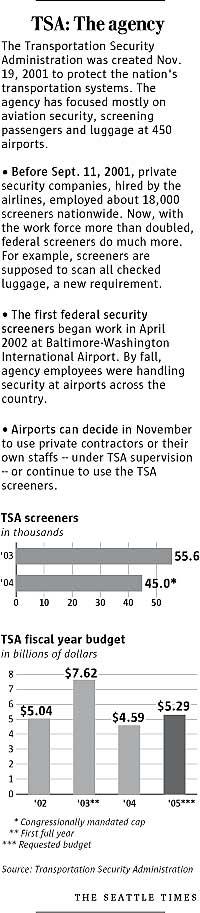

Congress continues to debate TSA's performance, and soon, airport operators will weigh in, too. In November, airports will be able to replace federal screeners with contractors or their own staffs, with TSA oversight. TSA spokesman Hatfield acknowledged the agency has struggled. But, he said, officials aggressively investigate reports of security problems and are trying to improve training and work conditions. TSA is creating layers of security, he said, so that if something is missed on one level, it will be caught at another. "We do not have a perfect screening system ... " Hatfield said. "It doesn't exist." An array of breaches Security breaches run the gamut, from unscreened bags in Houston to one wayward passenger in Minneapolis who walked past screeners unseen. In Portland, Ore., a supervisor handled a passenger's loaded gun at a checkpoint — TSA policy dictates calling police and not handling the weapon — and, in a separate incident, ignored multiple bags that tripped alarms on an explosives-scanning machine. The supervisor was promoted to temporary manager, and in that position he recently allowed two Marines to load an unlocked crate of M-16s and other weapons onto a plane, TSA employees said. Federal policy says the airline should have handled the weapons, and the crate should have been locked. In publicly reported incidents over the past 22 months, screeners missed at least a half-dozen guns and nearly 30 knives or box cutters. They also allowed at least 40 people to get past security without screening. Many more breaches have occurred but were not reported in the media, or even documented internally, employees say. Confusion at passenger checkpoints has produced one security breach after another. Screeners at X-ray machines have spotted possible weapons in luggage, only to have passengers grab those bags and walk off. Other passengers who set off metal detectors simply continued on their way. In Minneapolis, a passenger made his way into a concourse without being screened and was found aboard a flight bound for Salt Lake City. He was removed, screened and allowed to re-board, said a screener who wrote his U.S. senator about the breach. But other passengers who could have been handed a weapon were not rescreened until they reached Salt Lake City, the letter said, "and the pilot was NOT notified of the situation until he was on final approach ... " Supervisors give inconsistent orders. Remove passengers' shoes, some say. Don't remove their shoes, say others. When a passenger doesn't remove a laptop from a bag before sending it through the X-ray, guidelines say both items should receive extra scrutiny and be tested specifically for explosives.

Sometimes, screeners miss weapons because of equipment problems. In Boston, Richard Moughan, a screener until last October, said the quality of some X-ray machines was so poor "you couldn't even read them." Screeners provided The Times with images from machines that scan checked luggage for explosives. In one image, a gun was clearly visible but didn't trigger the alarm. Instead, a shoe did. In Houston, a large jar of fruit jelly, which has a density similar to some explosives, triggered the alarm on a machine that scans checked luggage. A supervisor, instead of calling explosive experts, wrapped a broomstick handle with plastic and used it to stir the jelly. Then he got a screwdriver and stirred the jelly again. Finally, he sealed the jar, repacked it, and sent the suitcase on its way. Only after screeners complained did anyone alert the passenger not to use the jelly. Airline infractions Sometimes, airport conveyor belts in Seattle accidentally send checked luggage to airline baggage handlers instead of TSA screeners. When that happens, baggage handlers are supposed to set the luggage aside for TSA.

A TSA supervisor, apprised of the situation, asked the same handler: "How do these bags get screened?" "They don't," the handler said. Three days later, TSA confronted the airline about loading unscreened luggage onto planes and ordered bags off three flights. Two months later, again in Seattle, Delta Air Lines was caught loading unscreened bags onto its planes and those of Hawaiian Airlines, TSA records show. One Delta employee told TSA he didn't ask permission to forgo regular screening because he couldn't find TSA's phone number. In all, eight Northwest, Delta and Hawaiian planes were loaded, or about to be loaded, with unscreened luggage. Records show TSA pursued fines exceeding $200,000 against the airlines and one airline employee, but the status of those fines is unclear. Northwest declined comment. Delta said it is in discussions with TSA. Some TSA employees attribute security shortcuts to the need to appease airlines. TSA policy dictates interior searches for a certain percentage of bags. Sometimes, screeners say, they skip that step and scan only the outside to keep up with heavy traffic.

"Otherwise, bags would not make the flight and the airlines start screaming because we cost them delivery charges, and they get on the horn and complain to D.C.," she said. "And that can't happen." In Portland, two TSA supervisors said they even saw airline managers using stopwatches to time screeners at passenger checkpoints. Bill Pickle, TSA's former security director in Denver and now head of security for the U.S. Senate, said: "The further we got from 9-11, every time we came to a Y in the road, we took the path of least resistance. The airlines began dictating what the mission of TSA would be." Airlines do want screening lines to be shorter so that passengers can depart on time, said Jack Evans, spokesman for the Air Transport Association of America, which represents leading U.S. airlines. At the same time, Evans said, airlines are concerned about security and don't want shortcuts.

TSA needs more resources, Evans said, to keep waits reasonable and ensure safety. TSA spokesman Hatfield said the agency doesn't allow airlines to pressure screeners or skirt security. TSA recommended fines against airlines in 257 instances between June 2003 and June 2004, he said. More incidents that could lead to additional fines are still being investigated. "We will not compromise or lower the security level to accommodate an airline schedule," Hatfield said. Judging performance The TSA was supposed to improve public safety by replacing low-paid, poorly trained private screeners with federal workers — salaried, motivated and looking to make security a career. But congressional investigators say they can't tell whether federal screeners are catching more weapons than their predecessors, who worked in a system that allowed terrorists carrying box cutters to board planes Sept. 11. To measure performance, inspectors use covert testing, trying to sneak guns, knives or bombs past airport screeners. For decades, screeners fared poorly. In 1978, they missed 13 percent of concealed weapons — a failure rate one report called "significant and alarming." By 1987, screeners were missing 20 percent. And the tests were easy. Weapons were simply placed with a few other items in carry-on luggage, and some inspectors could be recognized from earlier tests. Since 1997, covert-testing results have been confidential. But without disclosing numbers, government officials have expressed alarm at the results, even since federal screeners took over. The Department of Homeland Security's inspector general told Congress that federal screeners have performed poorly. Rep. John Mica, R-Fla., told The Times that the results were "disastrous." TSA says its own covert testing shows a 70 percent improvement over 18 months. But without knowing the starting point, that percentage says little about how screeners perform now.

From September 2002 to September 2003, TSA tested less than 1 percent of its work force. Pleas for more staff Time and again, TSA directors in charge of security at individual airports have warned top officials that without more people, safety will suffer and lines will grow. In late 2002, Isaac Richardson, then security director at Chicago's O'Hare International Airport, was desperate for more screeners. Without them, he feared missing a year-end deadline for using scanning machines to test checked luggage for explosives. "You have zero new hires for [O'Hare] for this week. This has to be a mistake!" he wrote in an e-mail to headquarters. So many airports had trouble making that deadline, it was extended a year. In December 2003, an advisory council of TSA security directors from airports around the country sent a memo to TSA's acting administrator, David Stone, warning of a "staffing crisis in the field." The group urged TSA to suspend employee cutbacks. "The continued decline in resources jeopardizes safety and morale as well as customer service," said the memo, written by council Chairwoman Marcia Florian, in charge of security at the Phoenix airport. This February, Florian wrote Stone again, saying the "serious staffing deficit" was growing. In April, Bob Blunk, then the Seattle airport's security director, wrote an e-mail to TSA headquarters, saying one of his biggest concerns was the "ability to conduct 100% baggage screening as summer passenger loads increase." Blunk wrote that Seattle needed 1,314 screeners but had only 1,063 — and about 100 of them were on leave for injury or military duty. But instead of authorizing more screeners, TSA approved a staffing level that simply matched the existing payroll of 964. "Remaining at or below this number will result in extraordinary delays in passenger processing and baggage screening this summer," Blunk wrote. In May, TSA removed Blunk and three of his top managers pending an investigation into management problems. The shake-up followed a petition by screeners, who complained of understaffing, lax security and promotion irregularities. Blunk's successor, John C. "Jack" Kelley Jr., initially said the airport could manage with a smaller staff through such measures as pulling employees from administrative duties to help during peak times. Then, in June, TSA announced it would hire 50 baggage screeners to help Seattle handle summer traffic. People aren't the only resource in short supply. In Seattle, managers brought in their own computer printers. One employee brought his own paper clips. Seattle screeners have used sensitive filters, designed to calibrate machines, for as long as three months past their six-month shelf life. Expired filters won't necessarily cause screeners to miss items. But they could lead to more false positives — and that means more bags would get searched, causing delays. Balancing act In its short history, TSA has struggled to satisfy Congress and the flying public. TSA's missteps have cost it political support. Congress capped TSA's work force at 45,000 in part because of its frustration with the agency. Some members of Congress became irate when a contractor hired by TSA to recruit screeners wound up billing the government $740 million — seven times its original contract. Lawmakers complain that TSA hasn't answered their questions promptly. The agency has yet to provide a good staffing analysis to justify its needs, said Congressman Mica, chairman of the House Subcommittee on Aviation. "It's taken six months for TSA to produce its latest staffing lists," Mica said. "By the time you get them, they're out of date." Many passengers aren't happy, either. In March, for example, about 2,700 wrote or called TSA to complain about rude treatment by screeners, mishandling of personal property, long lines or other concerns, TSA records show. The complaints represent a tiny percentage of the roughly 50 million people who fly each month. At the same time, they account only for passengers so angry they took formal action. Some gripes were about minor inconveniences. Others were more significant. Some travelers said screening lines were so long they missed their flight despite arriving 2-1/2 hours early. In June, Kimberly Bodley of Beaverton, Ore., complained to TSA that her 17-year-old son nearly missed his flight out of Seattle because screeners didn't know how to handle the syringes that he carried for diabetes. Her 93-year-old aunt offered this advice: "Oh, I don't tell them I have diabetes. I just wrap up my diabetic supplies really good and put them in the bottom of my carry-on. They've never even seen them." Back in Houston Concerns over security have prompted screeners in Seattle, Houston, Minneapolis and Denver to send letters and petitions to Congress and federal inspectors. In Seattle, screeners say their complaints are getting attention. But at other airports, warnings seem to go unheeded. After screeners in Houston wrote to Congress about the managers who sent unscreened luggage onto planes, their complaints yielded only an investigation by those same managers, screeners said. Screeners worried that what happened on March 12 could happen again. On June 21, it did. A power outage shut down all of the baggage-screening machines, said screener Clarice Gaines and three co-workers. In the passenger concourse, backup power allowed screening to continue. But downstairs, where checked luggage is scanned, only the conveyer belt had power. The scanning machines were shut down. This left TSA officials with the same problem they had encountered in March: unscreened baggage, and passengers waiting for flights. TSA managers told baggage screeners to unload the overflowing conveyer belt. The workers set the bags on the floor and awaited instructions. Gaines thought they would need to hand-search the more than 200 bags. But a manager checked with higher-ups and said that wasn't necessary. Within minutes, Southwest Airlines baggage handlers came in with carts, loaded the bags and put them on planes — unscreened. Cheryl Phillips: 206-464-2411 or cphillips@seattletimes.com Steve Miletich: 206-464-3302 or smiletich@seattletimes.com Ken Armstrong: 206-464-3730 or karmstrong@seattletimes.com Seattle Times staff reporters Christine Willmsen and Alyson Beery and news researchers Miyoko Wolf and Gene Balk contributed to this report.

Copyright © 2004 The Seattle Times Company

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

seattletimes.com home

Home delivery

| Contact us

| Search archive

| Site map

| Low-graphic

NWclassifieds

| NWsource

| Advertising info

| The Seattle Times Company