Originally published October 25, 2009 at 12:10 AM | Page modified December 23, 2009 at 5:28 PM

![]() Comments (0)

Comments (0)

![]() E-mail article

E-mail article

![]() Print

Print

![]() Share

Share

Part one | Reckless strategies doomed WaMu

Execs say WaMu fell victim to the economy &emp; but WaMu caused its demise by embracing risky loans and dismantling safeguards.

Seattle Times business reporter

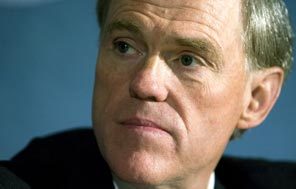

MANUEL BALCE CENETA / ASSOCIATED PRESS

Then-Washington Mutual CEO Kerry Killinger appears at a housing forum in December 2007. Earlier that year, even as the company grappled with rising loan defaults, he told analysts it was a great time for WaMu to take on new loans.

VIA BLOOMBERG NEWS

Kerry Killinger, right, rang the bell at the New York Stock Exchange in 2002. "Kerry's view of himself was tied to a constant increase in the stock price," said Fay Chapman, a former WaMu chief legal officer. "He was fixated on it."

LARA SWIMMER / VIA BLOOMBERG

WaMu opened its new headquarters building above the Seattle Art Museum in 2006. Two years later, the bank was seized by federal regulators.

The first of two parts

On Sept. 10, 2007, Washington Mutual CEO Kerry Killinger stood before an audience of analysts and money managers and assured them the Seattle-based thrift would come out of the housing slump stronger than ever.

WaMu, Killinger told the Lehman Brothers conference, had tightened its lending standards, could access plenty of cash, and was "picking and choosing carefully" when it came to making new loans.

"This frankly may be one of the best times I have ever seen for taking on new loans into our portfolio," he said.

But even as he spoke, WaMu was a dead bank walking. The company had plunged headlong into the business of making exotic, high-risk home loans, selling many of them to investors but holding onto others; now defaults on those loans were rising, and big investors had lost their taste for them.

Almost a year to the day after the Lehman conference, Killinger was fired. Two and a half weeks after that, federal regulators seized WaMu's banking units, effectively euthanizing a 119-year-old institution that had survived the Great Depression and the S&L crisis.

After its collapse, Killinger and other leading WaMu executives repeatedly deflected responsibility, saying the company fell victim to a housing slump turned global credit crisis that they foresaw but couldn't outrun.

But interviews with former WaMu executives and employees, along with government and internal company documents, reveal a far different picture, one of executives charting a reckless course that doomed the bank:

• In its headlong pursuit of growth, WaMu systematically dismantled or weakened the internal controls meant to prevent the bank from taking on too much risk — the very standards and practices that had helped it grow in the first place.

• WaMu's riskiest loans raked in money from high fees, but because the bank skimped on making sure borrowers could repay them, they eventually failed at disastrously high rates. As loans went bad, they sucked massive amounts of cash that WaMu needed to stay in business.

• WaMu's subprime home loans failed at the highest rates in nation. Foreclosure rates for subprime loans made from 2005 to 2007 — the peak of the boom — were calamitous. In the 10 hardest-hit cities, more than a third of WaMu subprime loans went into foreclosure.

By the summer of 2004, nearly 60 percent of the loans WaMu was making were the riskiest sort — option ARMs, subprime mortgages and home-equity loans.

![]()

WaMu's overall business strategy fueled its implosion. Since riskier loans had more profit potential than safer loans, the bank paid its loan consultants and independent mortgage brokers more for making them. It pressured appraisers to inflate home values. It told its underwriters to find ways to make loans "work," regardless of WaMu's own standards.

The strategy's momentum was so powerful and pervasive, one former top executive said, that the few dissenting voices inside upper management "were blown off." Rather than avoiding the housing bubble, he said, "Washington Mutual chose its destiny, to be right smack dab in the middle to the hilt."

"A cockeyed optimist"

Talk to people who worked with Killinger, and the same phrases and adjectives keep coming up. Ambitious. Quick study. Smartest guy in the room. And always, always optimistic.

"He's a cockeyed optimist to the nth degree," one former associate said. "He always thought he could get out of whatever trouble he was in."

But Killinger also is repeatedly described as avoiding confrontation and uninterested in the nuts-and-bolts details of WaMu's business. He declined to respond to specific questions posed by The Seattle Times.

"He could look at a financial statement and get to the heart of what was going on in a nanosecond," said Fay Chapman, WaMu's chief legal officer from 1997 to 2007. "But he could not have run a coffee stand. I just don't think his mind works that way."

And even more than most chief executives, insiders say, Killinger was focused on WaMu's stock price as the company's — and his — primary gauge of success. "Kerry's view of himself was tied to a constant increase in the stock price," Chapman said. "He was fixated on it."

Those traits all would play roles in WaMu's demise.

Killinger joined WaMu in 1982 after it bought Spokane's Murphey Favre stock brokerage, of which he was part owner. He rose rapidly, becoming president of the bank in 1988 and chief executive officer in 1990.

Killinger saw growth as the key to WaMu's future. Without growth, WaMu sooner or later would be picked off by some larger bank, as Seafirst and Rainier National Bank, among others, had been.

After a string of small and midsize deals gave WaMu a commanding position in the Northwest, in July 1996 it announced its biggest deal to date: the purchase of California-based American Savings for $2 billion in stock.

The deal was a turning point for WaMu. Not only did it double the thrift's size, but it introduced two practices that turbocharged WaMu's growth: pay-option adjustable-rate mortgages, commonly called option ARMs, and the "originate-to-sell" model of mortgage banking.

Option ARMs have become notorious as one of the main drivers of the mortgage bubble. With an option ARM, payments were based on a low "teaser rate" for the first few months (later just one month); then the rate adjusted and the "option" feature kicked in.

Each month, the borrower could make a payment that would fully pay off the principal and interest; one that covered just the interest; or a "minimum" payment based on the teaser rate, which wouldn't even cover all the interest owed. The unpaid interest was added to the loan's principal balance, shrinking the borrower's home equity. Option ARM customers frequently ended up owing more than they'd originally borrowed.

Option ARMs posed two big risks to borrowers: The interest rate adjusted monthly, rather than annually as with most standard ARMs, and once the unpaid interest hit a predetermined cap, the loan would effectively convert to a fixed-rate loan — typically with much higher monthly payments.

From a California-only product, option ARMs became widespread during the housing bubble, despite warnings from consumer advocates. The nonprofit Center for Responsible Lending called them "toxic mortgages" because of the threat of steep-payment shock and because the low teaser rates and minimum payments made them "ideally suited for misrepresentation."

Killinger hired Craig Davis, American's director of mortgage origination, to run WaMu's lending and financial services. Davis, several former WaMu executives said, began pushing WaMu to write more adjustable-rate mortgages, especially the lucrative option ARMs.

"He only wanted production," said Lee Lannoye, WaMu's former executive vice president of corporate administration. "It was someone else's problem to worry about credit quality, all the details."

Up to that point, WaMu held on to most of the mortgages it made. Now it began bundling ARMs and certain other mortgages into securities and selling them off — pocketing hundreds of millions of dollars in fees immediately, while offloading any potential repayment problems.

Chapman, the former chief legal officer, said she and some other WaMu executives "argued vociferously" against the shift, saying it didn't fit WaMu's traditional emphasis on lending mainly to its own banking customers.

But Davis and other executives from American Savings "didn't want to give it up. It was what they knew how to do, and they made a huge amount of money on it."

Killinger backed the push to generate more and more mortgages to be packaged and sold, allowing that to dominate the entire home-loan operation. WaMu turned again to California for its entree to the murky world of subprime lending, buying Long Beach Mortgage in 1999.

Though Long Beach was lucrative, some executives argued against the deal.

"It didn't fit our culture," Lannoye said. "It's hard to say you're a 'friend of the family' when you have an entity like Long Beach that's making loans to people at higher rates than they had to pay because they didn't know any better. I didn't want to have to sit in front of a regulator and explain why an African-American borrower (from Long Beach Mortgage) was paying two percentage points higher than a borrower from WaMu."

The frenzy peaks

WaMu's acquisition spree, along with its plan to open branches in metro areas from coast to coast, was meant to transform the stodgy Northwest thrift into a national consumer-banking powerhouse. And it worked, for a while. By 2002, WaMu was the sixth-largest financial institution in the country. The stock hit its all-time high of $46.55 on Nov. 23, 2003.

But for the next 3 ½ years the shares languished, seldom rising much above $45 or falling below $40. This only confirmed Forbes magazine's description of Killinger's cherished company as "the world's tallest midget."

As the great refinancing boom of 2002-03 tapered off, competition intensified among mortgage lenders to write, close and package as many loans as possible. Countrywide Financial in particular, which had led the industry by cutting the teaser rate on its option ARMs to 1 percent, was seen as a threat.

Countrywide "was held up as the competitor, because they would do anything — low-doc, no-doc, subprime, no money down," said Tom Golon, a former senior home-loan consultant for WaMu in Seattle. The WaMu staff was subjected to "total blanketing — e-mails, memos, meetings set up so people understood that this was what the company wanted them to do."

If Countrywide's unofficial motto was "Price any loan!", WaMu's response was "The power of yes." In ways large and small, the company made it clear that it wanted its loan consultants to make a lot more loans — especially the riskier but potentially more lucrative ones.

The most direct way was by paying them more to do so. A compensation grid from 2007 — the same year Killinger told investors that WaMu was reining in its home-loans operation — shows the company paid the highest commissions on option ARMs, subprime loans and home-equity loans: A $300,000 option ARM, for example, would earn a $1,200 commission, versus $960 for a fixed-rate loan of the same amount. The rates increased as a consultant made more loans; some regularly pulled down six-figure incomes.

WaMu also began allowing more "low-documentation" loans — those in which a borrower didn't need to submit bank statements, pay stubs or other proof of earning enough money to repay the loan. Instead, the company leaned more and more heavily on credit scores, which could be ascertained while the borrower was still on the phone.

"The big saying was 'A skinny file is a good file,' " said Nancy Erken, a WaMu loan consultant in Seattle. She recalled helping credit-challenged borrowers collect canceled checks, explanatory letters and other documentation that they could afford their loans.

"I'd take the files over to the processing center in Bellevue and they'd tell me 'Nancy, why do you have all this stuff in here? We're just going to take this stuff and throw it out,' " she said.

In time, WaMu even began allowing low- or no-documentation option ARMs, piling risk on risk. The loose standards spread through the company like a flu virus.

"I don't think Killinger intentionally set out to cut corners," said one senior executive who spoke on condition of anonymity. "But he certainly created an atmosphere in which doing the easy thing rather than the hard thing was OK."

Even the most notorious murder case of the 1990s made a cameo appearance, as Chapman learned in early 2007.

"Someone in Florida had made a second-mortgage loan to O.J. Simpson, and I just about blew my top, because there was this huge judgment against him from his wife's parents," she recalled. Simpson had been acquitted of killing his wife Nicole and her friend but was later found liable for their deaths in a civil lawsuit; that judgment took precedence over other debts, such as if Simpson defaulted on his WaMu loan.

"When I asked how we could possibly foreclose on it, they said there was a letter in the file from O.J. Simpson saying 'the judgment is no good, because I didn't do it.' "

As standards eroded, WaMu's option-ARM volume exploded — from less than $5 billion in the first quarter of 2003 to $19.6 billion in the second quarter of 2005. WaMu bundled many of its option ARMs into securities as fast as they could be written and sold them to investors, who thought the higher yields justified the added risk.

"(Chief operating officer Stephen) Rotella told me they could sell (option ARMs) off for four times what they could get for fixed-rate loans," said Golon, the former loan consultant. "There was a class of willing buyers for these out there who wanted more risk."

Over at Long Beach Mortgage, the subprime unit was making a lot of 2/28 and 3/27 ARMs, in which the interest rate was fixed for two or three years but floated afterward.

"They were just nasty products — just awful for the consumers — and even at that relatively early date they were performing badly," Chapman said.

In fact, in the 10 cities with the worst foreclosure rates on less-than-prime loans from 2005 to 2007, Long Beach Mortgage had the highest failure rate in eight of them, according to an analysis last year by the federal Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. Its dismal performance included 22 percent in Miami, 41 percent in Sacramento and 54 percent in Cleveland.

Overall, 34.1 percent of WaMu subprime loans went into foreclosure in those 10 markets — more than three times the 10.2 percent rate of archrival Countrywide.

What controls?

As WaMu was weakening its lending standards, it was making sure its underwriters and credit-risk managers wouldn't get in the way.

In an internal newsletter dated Oct. 31, 2005, and obtained by The Seattle Times, risk managers were told they needed to "shift (their) ways of thinking" away from acting as a "regulatory burden" on the company's lending operations and toward being a "customer service" that supported WaMu's five-year growth plan.

Risk managers were to rely less on examining borrowers' documentation individually and more on automated processes, Melissa Martinez, WaMu's chief compliance and risk oversight officer, wrote in the memo.

Soon after, WaMu's risk managers were called to an "all-hands" meeting at the company's posh new conference center near Seattle-Tacoma International Airport. Dale George, a former senior credit-risk officer in Irvine, Calif., recalled that Martinez emphasized "the softer side of risk management" at the meeting.

"The whole tone it set was that 'Maybe the next file I review I should pull back, hold off on downgrading (a loan), not take a sharp pencil to what production was doing,' " he said.

"They weren't going to have risk management get in the way of what they wanted to do, which was basically lend the customers more money."

And as WaMu was loading up on option ARMs and other exotic loans, the computer model it used to determine how risky its portfolio was had not been updated to fully take such loans into account.

An internal "Corporate Risk Oversight Report," dated September 2005, noted that the model's ability to predict losses "is untested on products with the potential to negatively amortize" — that is, products like the option ARM.

"Given recent production and interest rate trends," the report continued, "negative amortization is a major and growing risk factor in our portfolio." It recommended that the model be tested to make sure it predicted higher losses from negative-amortization loans, especially in times of economic stress.

In response, WaMu managers said the model had been tested on historical loan data, including option ARMs, from 1999 through 2004, and that the only action needed was to clarify the model's documentation.

However, for most of that period option ARMs were a relatively small part of WaMu's loan mix, and they weren't marketed to the broad range of customers that they ultimately were. In fact, once the housing bubble popped the failure rate on option ARMs rose rapidly, and WaMu had to set aside billions more than originally planned to offset those losses.

WaMu also has been accused, by individuals as well as New York Attorney General Andrew Cuomo, of pressuring appraisers — its own and outside contractors — to inflate the value of real estate.

Inflated appraisals meant WaMu could write bigger loans against a given property — sticking borrowers with bigger payments in the process. They also meant a given loan amount would be a smaller percentage of the home's appraised value, making the loan appear less risky.

The unraveling

Even when Wall Street's appetite for mortgages knew no bounds, WaMu kept many of the riskiest loans on its own books — boosting short-term profits but giving it far greater direct exposure to the eventual meltdown than competitors such as Chase and Wells Fargo.

Beginning in 2007, those high-risk loans went sour so quickly and in such volume that WaMu couldn't keep up.

Banks have to set aside money to offset loans they expect to go bad. When more loans do so than anticipated, the bank has to add more money to its loss reserve — cutting into profits.

At the end of 2007, $6.1 billion of WaMu's loans were in "nonaccrual" — bank-speak meaning that WaMu no longer expected to get all the money due it. Over the course of that year, WaMu set aside $3.1 billion for loan losses and posted a $67 million loss, its first in decades.

By mid-2008, WaMu's problem loans had ballooned to $9.7 billion. The bank had to set aside nearly that much to cover losses, and it lost a staggering $7.9 billion in the first half of the year alone.

In effect, WaMu had run through the billions of dollars it raised that spring from outside investors — not in building the business, but in shoveling cash into the hole it had dug for itself. And no one could tell how much deeper the hole would get.

WaMu's shaky condition spooked depositors, who began withdrawing large sums in July and August 2008. The run eased in late August but reignited the next month, after Killinger was fired and rumors were rife that WaMu would be sold or shut down.

More than $17 billion flew out the door between Sept. 5 and 25, when federal regulators finally pulled the plug on Killinger's dream of a banking Wal-Mart.

In the end, said Bill Longbrake, WaMu's longtime chief financial officer, the bank failed because its leaders abandoned its historical balance between growth and prudence.

"You have to be willing, when the external world is haywire, to lose market share and profits," he said. "They could have stepped back."

Drew DeSilver: 206-464-3145 or ddesilver@seattletimes.com

UPDATE - 09:46 AM

Exxon Mobil wins ruling in Alaska oil spill case

UPDATE - 09:32 AM

Bank stocks push indexes higher; oil prices dip

UPDATE - 08:04 AM

Ford CEO Mulally gets $56.5M in stock award

UPDATE - 07:54 AM

Underwater mortgages rise as home prices fall

NEW - 09:43 AM

Warner Bros. to offer movie rentals on Facebook

More Business & Technology headlines...

Entertainment | Top Video | World | Offbeat Video | Sci-Tech

general classifieds

Garage & estate salesFurniture & home furnishings

Electronics

just listed

More listings

POST A FREE LISTING