Second of three parts

Push to make Haiti an e-cash economy fell far short

The Gates Foundation, Mercy Corps and others hoped ‘mobile wallets’ — cash disbursed via cellphones — would propel Haitians to new level of economic and financial security. Initial success gave way to failure, but now locals are reviving this effort to leapfrog into the future.

Mike Siegel / The Seattle Times

In the Jalousie neighborhood above Port-au-Prince, the Haitian government spent $1.4 million to paint the slum homes in different colors to cheer things up. The introduction of e-cash, distributed through cellphones, was touted as a way to benefit residents of poor neighborhoods like this one.

Mike Siegel / The Seattle Times

Click to enlarge | Johanna Joseph, at a payment agent’s window, watches for $40 to appear on her cellphone’s “mobile wallet.’

By Ángel González

Seattle Times business reporter

CARREFOUR, Haiti — In the Western Hemisphere’s poorest country, few people have bank accounts. But cheap cellphones are ubiquitous, and for people like Johanna Joseph, they are the sole link with any form of banking.

While most Haitians store their wealth in the form of crumpled, grimy bills, Joseph gets a monthly stipend from the government deposited directly into an electronic cash account tied to her cellphone.

One afternoon last November, the 28-year-old mother of two used the system for the first time. She withdrew the equivalent of $40 in local currency at a poorly lit shop in Carrefour, a down-and-out suburb of Port-au-Prince that still bears the scars of the 2010 earthquake.

“I’ll use the money to buy shoes,” she said.

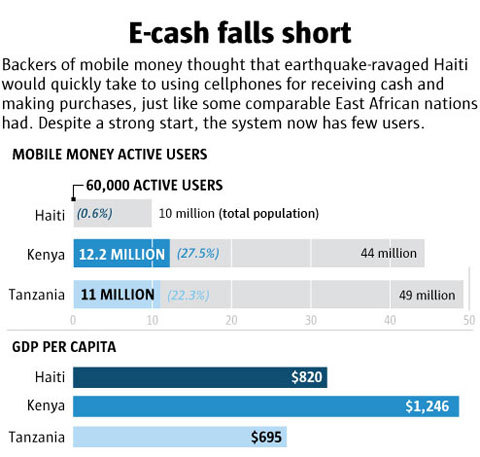

About 60,000 people in Haiti use these so-called “mobile wallets” — electronically transferring money to relatives and friends across the country, or simply keeping it safe from thieves. For them, no more worn-out gourdes, as the local currency is called, stashed under the mattress.

In a country of 10 million, however, that number is a disappointment. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and other fans of the technology hoped that following the earthquake, mobile wallets would take off here as they did in Kenya, where a large percentage of households use it.

But Haiti has long confounded even the best-funded development efforts.

Mike Siegel / The Seattle Times

Port-au-Prince Bay is visible from the headquarters of Digicel, Haiti’s largest cellphone company and a key player in efforts to create an electronic-cash system using mobile phones to store money, make payments and move the nation’s economy forward.

Such potential

The earthquake-ravaged nation seemed like the perfect place to establish electronic cash.

Lots of nonprofits wanted to funnel billions of relief dollars directly to recipients without going through a government they mistrusted. Boosted by a $10 million incentive from the Gates Foundation and the US Agency for International Development (USAID), e-cash here got off to a strong start.

The two main cellphone operators scrambled to get their subscribers to open accounts. One of the wireless companies was Voilà, owned by Bellevue-based Trilogy International Partners — which in 2010 was the largest U.S. investor in Haiti.

The aim was to get 1 million users active in two years, said Claude Clodomir, who heads HIFIVE, the project that spearheads the Haitian mobile cash effort with backing from the Gates Foundation and USAID.

“They wanted Kenya,” said Clodomir. “It’s been harder than we thought.”

Implementers blame tough logistics, cautious regulators and poorly designed incentives for the effort falling so short of its goal.

Yet mobile cash seems to be getting a second wind this year, as new companies enter the fray and regulators have become used to it.

“Cash will disappear,” Clodomir said confidently in an interview at his organization’s headquarters in Petionville, a relatively wealthy suburb of the capital. “It’s going to take some time, but we’re on the right side here.”

Mike Siegel / The Seattle Times

Click to enlarge | Marketplaces in Haiti, like this one near the capital of Port-au-Prince, are crowded with people selling everything from live chickens to cellphones. Backers of mobile-wallet technology say replacing scarce and dirty cash with e-cash would give the local economy a boost.

Uphill battle

In Haiti, roads are often impassable, and banks were scarce even before the 2010 earthquake wiped out a third of their locations. Only one out of five Haitians has a bank account.

Cash is also a problem: The colorful gourde bills soon become torn and dark with grime as they are passed through the dirty streets of Port-au-Prince and other cities.

People who don’t have wallets crumple the currency into little balls, and sometimes “put it in their socks,” said Maarten Boute, the Belgian-born president of Digicel Haiti, the country’s largest cellphone operator.

Mike Siegel / The Seattle Times

Click to enlarge | This building in Port-au-Prince still shows damage caused by the devastating earthquake of Jan. 12, 2010, which killed more than 200,000 people in Haiti.

Yet cellphones are everywhere, thanks in great part to Boute’s company, which is owned by Irish billionaire Denis O’Brien. Cheap, pre-smartphone handsets are in the hands of more than 6 million Haitians, or 60 percent of the population, up 15-fold in a decade. Street vendors sell SIM cards for the equivalent of 50 U.S. cents.

It means farmers can call their relatives in town to learn about local prices for produce, and people can call radio talk shows to complain about the government.

“Suddenly everyone has a voice,” Boute said.

Mobile wallets seemed like a good fit, especially to the rich nonprofits flooding the country after the quake.

Bradley Horwitz, president of Trilogy, the Bellevue telecom firm that formerly owned Voilà, says that his company heard 40 cents out of every dollar spent by nonprofits distributing cash to Haitians was consumed by the NGOs’ security and administration costs. (Voilà was sold to Digicel in 2012).

Also, nonprofits were befuddled at the complexity of managing checking accounts and employee payrolls in Haiti.

“A mobile wallet solution was perfect to make these programs more efficient,” he said.

Mercy Corps, a nonprofit founded in Seattle and based in Portland, used Voilà’s mobile wallet to distribute cash to inhabitants of a small community in St. Marc, in central Haiti. The e-cash could be spent buying a few specific products — firewood, food — from a small number of merchants authorized by the program.

New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof lauded the project in a column titled, “I’ve seen the future (in Haiti.)”

Garland Potts / The Seattle Times

Source: SAFARCOM, HIFIVE, GSMA, World Bank

Click to enlarge

Mike Siegel / The Seattle Times

Click to enlarge | In the center of Port-au-Prince, two boys pose in front of the Notre Dame Cathedral, which was destroyed during the January 2010 quake.

In Kenya, e-cash took off because it helped migrants working in the capital send money home to the provinces. It also became a steppingstone to financial services such as borrowing for small-scale businesses, which development experts see as critical to lifting an economy out of poverty.

The Gates Foundation, long a proponent of e-cash in the developing world, designed an incentive program to spur Haiti’s mobile operators to enter the market. It offered $10 million in incentives if the cellphone companies produced 5 million transactions.

Digicel is one of the most recognizable brands in Haiti; red umbrellas marked with its logo line the country’s streets, the sole source of shade for many vendors. The company threw its marketing weight behind the scheme.

In his office high in one of Haiti’s few office towers, in the bustling Turgeau district, Boute said his staff “ran like mad” to develop a network of agents who worked the streets drumming up customers even during political riots “to get those transactions done so we could get the award.”

At the beginning, the e-money transactions were free, and so were payroll services for companies.

More than 800,000 people registered for the competing mobile money services from Digicel and Voilà. In a 2012 presentation, an affiliate of the World Bank called Haiti the fastest growing mobile money market in the world. Both Digicel and Voilà claimed their Gates Foundation incentive money in mid-2012.

Mike Siegel / The Seattle Times

A man climbs atop a tomb and throws scores of bills at pilgrims to the Port-au-Prince cemetery during the Nov. 1 Fête ged Guédés, which celebrates the spirits of the dead.

But it was soon evident that Haiti wouldn’t be another Kenya. As the immediate relief programs that electronically distributed cash from nonprofits such as Mercy Corps petered out, so did use of the mobile wallets, said HIFIVE’s Clodomir.

After earning the incentive funds, Digicel “pulled back on the effort” of aggressively promoting the service, said Boute.

Mark McGrath, director of sales for Digicel, said that when the promotions stopped, there was not enough business to spur the company’s network of agents to carry the real currency needed to allow subscribers to cash out as they pleased.

Haitian regulators were also more cautious than their laissez-faire Kenyan counterparts, in part because of their long battle with corruption and drug money laundering.

“People are very attached to cash. When you tell people that their money is going to be deposited into their telephone, they freak out.”

Pascale Elie, Lajan Cash Manager

They required telecommunication companies to partner up with banks and set up tough screening rules for large mobile wallets, which stifled the usefulness of such accounts among unregistered, informal merchants. The most common kind of account is still limited to about $100.

Boute and Horwitz both said they had warned the Gates Foundation about the design of the incentives that awarded the wireless companies millions for generating lots of short-term transactions. These were “a bit of a curse,” Boute said.

Rodger Voorhies, director of the Gates Foundation’s Financial Services for the Poor program, said the Haiti was both a “great success and a great lesson.”

It was one of the Gates Foundation’s first big efforts in mobile money. Cellphone operators were spurred to create a lot of usage very quickly because the disrupted Haitian economy badly needed it, and the effort accomplished that, Voorhies said.

But nowadays the foundation, using what it learned from the Haitian experience, takes “a more holistic approach” that includes getting regulators and international organizations on board and making sure the infrastructure is in place to support the system. It also aims for more long-term growth, he said.

The foundation’s e-cash efforts now focus on eight countries, from Nigeria to Bangladesh, a nation Voorhies called a “sprinter” in terms of mobile wallet adoption. Mobile cash remains a critical tool against financial exclusion, which in turn is a huge cause of social exclusion, he said.

This player was created in September 2012 to update the design of the embed player with chromeless buttons. It is used in all embedded video on The Seattle Times as well as outside sites.

Mike Siegel / The Seattle Times

Driving down the street in Haiti’s capital, Port-au-Prince.

Mike Siegel / The Seattle Times

Click to enlarge | Tap-tap vehicles serve as public transportation in Haiti. To use them, you pay the driver a small fee to get on, then “tap tap” the side of the vehicle to alert the driver when you want to get off.

Not giving up

Years after the promotion blitz for e-cash in Haiti ended, there’s a small universe of mobile wallet users who find the system useful. In dozens of businesses around the country, such as Delimart, a supermarket geared to middle-class Haitians, one can pay with mobile cash.

Opening a mobile money account using Digicel’s TchoTcho service is remarkably easy: Just by dialing a code on one’s cellphone, one can instantly open an account that can hold about $80. To open a bigger account for up to $214, a user must visit a Digicel agent. Sending money costs 1 percent of the transferred amount; withdrawing $25 in Haitian currency costs about 2 percent.

Mike Siegel / The Seattle Times

Click to enlarge | Sanon Arnold, right, and his family, stand near the ruins of what he said had been his five-story house in the poor Port-au-Prince neighborhood of Bicentennaire.

Jocelyn Romilus-Joseph, a 24-year-old student in Port-au-Prince, said he is a convert; he receives money from family in western Haiti using TchoTcho.

“They need to do more marketing,” the 24-year-old said. “A lot of people don't know how to do it.”

Sanon Arnold, a 55-year-old man who stood near the ruins of what he said had been his five-story house in the impoverished neighborhood of Bicentennaire, also uses the system. “It’s safe,” he said.

Clodomir said he is now focusing on getting companies, including the large textile factories that are Haiti’s top industrial employers, to use mobile wallets for their payroll.

Digicel’s McGrath said that there was a big ramp-up in mobile money transactions in September, after the company set up new incentives for its legions of street vendors to join the e-cash ecosystem.

Nonprofits are also delving back into e-cash. Mercy Corps, which pioneered e-cash in Haiti, now is trying to encourage neighborhood savings clubs to adopt mobile money accounts.

The benefits are clear. During a visit in November to such a club in Carrefour-Feuilles, the club’s secretary counted piles of gourdes that had been neatly unwrinkled and put into a gray metal box held shut with three small locks.

The box held nearly 24,000 gourdes, the equivalent of five months of pay for a textile worker. The cash is intended to help members get through financial emergencies or pursue personal projects, but it’s a temptation to criminals in a neighborhood brimming with people barely making it.

Frandy Joachim, the 40-year-old club secretary who painstakingly counted the money, says he approves of the idea. But Treasurer Davina Jean, the 34-year-old unemployed nurse who is in charge of keeping the metal box safe, is among the skeptics. Although mobile wallets are easy to use, she says, the box “is even easier, because the money is right there.”

Haitian entrepreneurs are also starting to see opportunity. One of the stately gingerbread mansions for which Port-au-Prince was once known houses the team behind Lajan Cash, a mobile money project launched in 2013 by local businessmen and a state bank, the Banque Nationale de Credit.

Credits

Reporter: Ángel González

Photographer / videographer: Mike Siegel

Project editor: Rami Grunbaum

Producer / Web designer: Gina Cole

Print designer: Bob Warcup

Copy editor: Karl Neice

Graphic artists: Mark Nowlin, Garland Potts

Photo editor: Fred Nelson

Video editor: Lauren Frohne

Their technology, which allows people to tie their mobile wallet to any mobile phone network, is the one Mercy Corps is going to adopt.

Lajan Cash manager Pascale Élie says she’s optimistic. Her service has garnered 20,000 users, a third of the total number of mobile wallet users in the country (and a larger customer base than Haiti’s 16,000 credit card holders).

The Montreal-educated executive says mobile wallets are the best alternative for bringing the many Haitians who lack addresses and formal jobs into the financial system.

But she acknowledges that it will take time.

“People are very attached to cash,” she said. “When you tell people that their money is going to be deposited into their telephone, they freak out.”

Ángel González: 206-464-2250 or agonzalez@seattletimes.com. On Twitter: @gonzalezseattle.